Lightweight Musical Chiffon

Valentyn Silvestrov Musical Universe

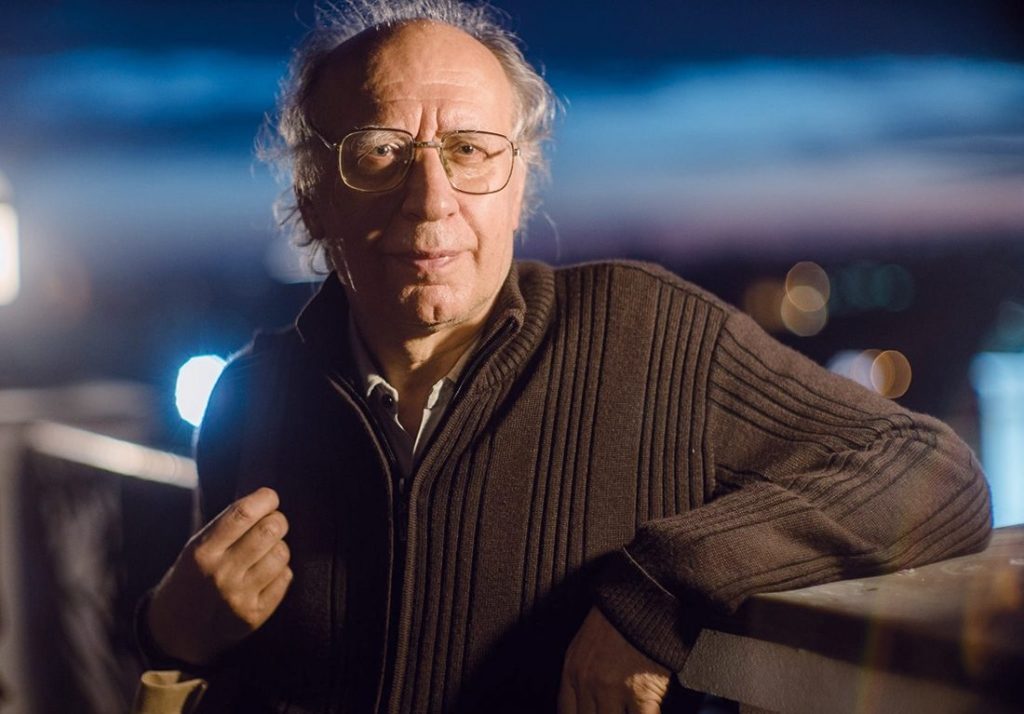

The name of Ukrainian composer Valentyn Silvestrov [Валентин Сильвестров] is widely known both in his homeland and abroad. Just the mention of his name creates a whole spectrum of various associations in the minds of connoisseurs of contemporary classical music. Silvestrov is one of the most famous Ukrainian composers; it took a long way for his music to reach his listeners, but eventually it attracted many admirers. He is a dissident by nature and, according to his own statement, has never tried to make a career. Yet he has achieved considerable popularity and exerted influence on a large audience. Silvestrov received many significant awards, both international and national, such as the Serge Koussevitzky International Prize (USA, 1967), the Gaudeamus International Composers Award (the Netherlands, 1970), the People’s Artist of Ukraine (1989) and Taras Shevchenko State Prize of Ukraine (1995), which is the highest artistic award in his home country. Silvestrov is an outsider, who paradoxically does not shy away from publicity. The number of published and filmed interviews and dialogues with Silvestrov is immense. Silvestrov was an avant-gardist and is now a typical representative of the post-avant-garde, who created his unique “metaphorical style.” He also composed music settings of the Ukrainian National Anthem, as a kind of spiritual struggle for Ukraine. All these paradoxical characteristics create and image of a composer with strong convictions and passionate personality. Valentyn Silvestrov’s life is tightly knit with creative act – these modes are an inseparable unity – for him, the most important events are sounds, emotional and intellectual discoveries, reflections, encounters, and conversations. His biography may not be packed with facts, but it is full of creativity, exploration, and affirmation of the spirit.

photo: stereo.ru

The beginning

Valentyn Silvestrov’s entire life is connected to Kyiv, where he was born on September 30, 1937. He began to study music seriously only at the age of fifteen. Following his persistent requests, his parents bought him a piano. As the composer himself recalls, “I had a childish belief that as soon as I sat down at the piano, I would immediately start playing music. … When the instrument arrived, I was somehow convinced that I would play right away, without any practicing. And I was surprised that, as it turned out, this was impossible. So, I had to start taking piano lessons.” 1 Silvestrov’s first piano teacher was Sofya Rybinska. It was at this time that he began to create his own compositions, which were performed much later. (For example, the piano waltz of 1952 was included in the cycle Naïve Music, 1993.) Having completed secondary school, Silvestrov entered Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture, but continued his music education at the Evening Music School (1956–58). The final transition to the field of music took place in the winter of 1958, when he transferred from the sixth semester of the Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture to the second semester at the Kyiv Conservatory. 2. I would like to emphasize this fact, which seems inconceivable today: Silvestrov was admitted to the conservatory without any entrance exams, as a transfer student from another educational institution, majoring in a different subject, only because the professors had heard his compositions, appreciated his talent, and made efforts to resolve all bureaucratic procedures. He started studying in the studio of one of the most prominent Ukrainian composers of the 20th century – Borys Lyatoshynsky (Бориис Лятошинський, 1895–1968).

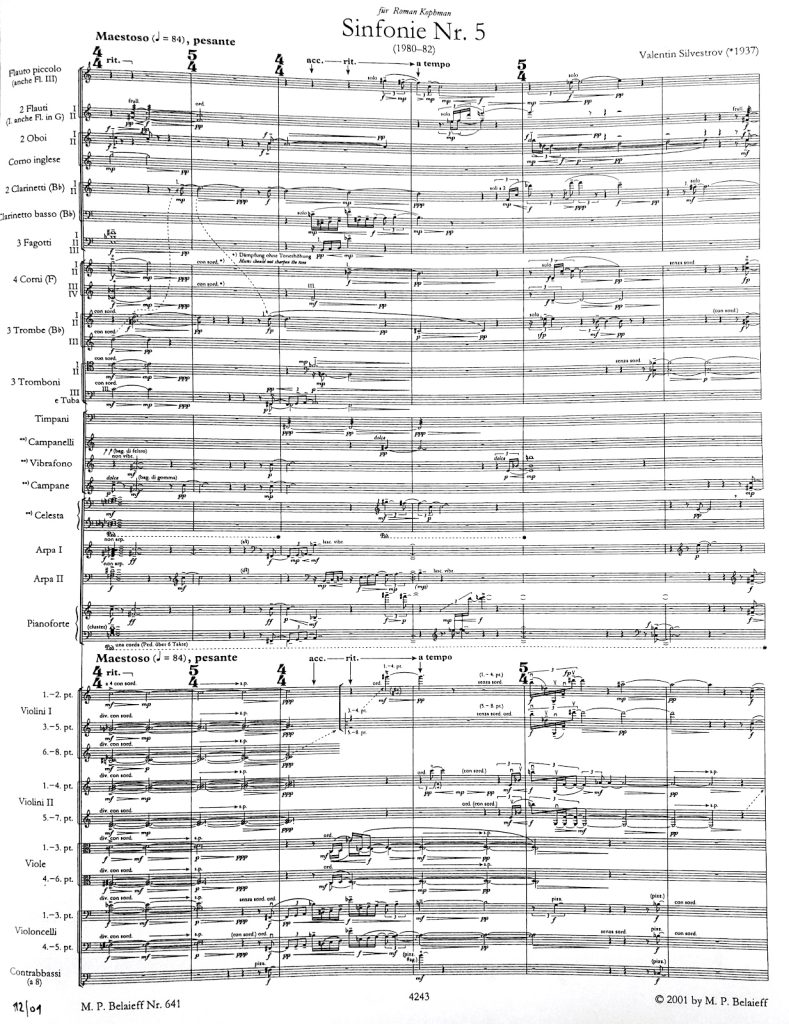

During his studies at the conservatory (1958–63), Silvestrov composed, among other works, Five Pieces for piano (1961) and Triad (1962), the Quartetto piccolo for strings (1961), the Trio for flute, trumpet, and celesta (1962), and the Symphony no. 1 (1963/ 1974). These works demonstrate the composer’s mastery of contemporary compositional techniques of the time, and serialism in particular.

Looking back at the beginning of Silvestrov’s creative path, studying composition in Lyatoshynsky’s studio was a real blessing for him. Lyatoshynsky was probably the most progressive professor at the conservatory, and an expert in recent European musical innovations, who supported his students and gave them the opportunity to develop in many ways. It was from Lyatoshynsky’s studio that the majority of composers who are known for their sound experiments and innovations came.

The avant-garde

At the very beginning of the 1960s, Valentyn Silvestrov became an active member of a group of young musicians that became to be known as the Kyiv avant-garde. The group included the conductor Ihor Blazhkov (Ігор Блажков, b. 1936), composers — students of Lyatoshynsky’s studio – Vitaly Hodziatsky (Віталій Годзяцький, b. 1936), Leonid Hrabovsky (Леонід Грабовський, b. 1935), Volodymyr Huba (Володимир Губа, 1938–2020), Volodymyr Zahortsev (Володимир Загорцев, 1944–2010) and others. The purpose of the meetings of the Kyiv avant-garde artists was to study the works of the leading European composers of that time, and to master the contemporary compositional techniques. They didn’t do anything that would seem illegal to us today. It is possible, however, to understand the significance of their activities only in the context of the ideological atmosphere of the Soviet Union.

According to the Soviet policies, all artistic activity had to follow “ideologically correct” aesthetics, called socialist realism. In the field of music, socialist realism was defined not only according to the thematic content of musical works, such as glorification of the political elite, party congresses, labor heroes, etc., but also according to the means of expression, such as the tonal system in the classical-romantic style, the traditional structural, textural, and orchestral means. All music that did not correspond to these demands was labeled as formalism, was mercilessly criticized, and was not allowed to be performed. (One of the victims of such a witch hunt for formalists was Lyatoshynsky, Silvestrov’s teacher.) The Khrushchev Thaw – the period that started with the debunking of Stalin’s personality cult – did not radically change the situation, especially in Ukraine, where censorship was probably the strongest compared to other republics of the former USSR. Under these conditions, any interest in the music of the Second Viennese School and the European post-war avant-garde, the works of Anton Webern, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, and others, was officially unacceptable. It was for this reason that Kyiv avant-garde group gathered in the apartment of Silvestrov’s parents secretly, to study the scores of new music, which they acquired while overcoming many obstacles. One of the sources of information about contemporary music was the Warsaw Autumn festival (Kyiv composers were able to get the recordings of these concerts.) Notably, the activities of the Kyiv avant-garde group were discussed in the article A Letter from Kyiv by Ukrainian musicologist Halyna Mokreeva, which was published in the magazine “Ruch Muzyczny” in 1962. It was after this publication that the soviet bureaucrats began to pay closer attention to the young musicians and began to apply repressive measures to them – both in terms of creative work and social life – which in some cases led to tangible negative consequences.

In Silvestrov’s case, the commitment to the avant-garde aesthetics led to his expulsion from the Union of Composers in 1970. He compared this event to murder: “At that time, the expulsion from the Union was akin to strangulation – all our oxygen channels were blocked.”3 It should be noted that in the Soviet Union an artist without a membership in a creative union was not allowed to work as a professional of their field, and faced starvation as one of the alternatives. For composers this meant that any performance of their music was not allowed, that the state would not purchase their works (which was one of the sources of income), and generally they were not allowed to conduct any music activities. Silvestrov was reinstated in the Union in 1973 as a result of much effort – only after he, together with his colleagues, wrote a letter to Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturyan and Kara Karaev.

It was against the backdrop of such confrontations, that Silvestrov’s avant-garde period, lasting until the early 1970s, unfolded. For more than ten years, he had created numerous compositions that combined technical precision, conceptual excellence, and perfect structure.

Notably, Silvestrov’s oeuvre does not include so-called “transitional” compositions that would prepare ground for a climax of any particular period. Each opus is both self-sufficient and a link between previous and subsequent compositions. In the 1960s, Silvestrov composed works in all genres that became characteristic for his oeuvre in general: three symphonies, the chamber symphony Spectra (1965), Mysteriya for alto flute and six percussion groups (1964), Projections for harpsichord, vibraphone and bells (1965), various piano pieces and romances. In these works dodecaphonic and aleatoric techniques, atonal and polytonal methods of sound organization, pointillist texture and sonoristics are used; notation is on the verge between traditional five-lines and graphic scores. That is, these works correspond to the dominant avant-garde direction in European music, which is reflected in the choice of techniques, the selection of instruments, and at the conceptual level. Silvestrov’s abovementioned and other compositions of avant-garde period are still fascinating. Any demanding listener who encounters them would be pleasantly surprised, as they include contemplation of sound itself, unexpected timbral combinations and experiments with texture, unpredictable change in background and foreground sound, and nuanced dynamics and tempos. These characteristics are certainly aimed at creating a wide variety of emotions, from static contemplation of time to expressivity. The attention to natural processes and phenomena brings Silvestrov’s compositions of this period closer to the works of representatives of European post-war avant-garde (Yannis Xenakis, Luigi Nono, György Ligeti, and Karlheinz Stockhausen). The composer explains: “The point is that nature is also music, and if you have an ear, you hear it. The sounds of nature should interest any musician it terms of their musical essence. … I drew inspiration from nature in my avant-garde works, as if borrowing its sonic processes, which have a musical origin, or generate emotions, such as sadness. For example, the sound of the wind, or rather its breath.”4

During the same period, Silvestrov’s works began to be performed, and his name became known in the USSR, even though in the category of a “forbidden” composer. He also received awards from international organizations. Silvestrov’s circle of colleagues and friends includes those who share his position and aspirations, such as Andrei Volkonsky, Edison Denisov, Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Alexander Kneifel, Gia Kancheli, Tigran Mansuryan, Arvo Pärt, and others.

Metaphorical music

In the early 1970s, Silvestrov’s musical language started gradually changing. At this time, the transition to a new musical language was typical for many composers who had experimented with the avant-garde techniques in the 1960s. Everyone was certainly searching for their unique ways, yet some common trends can be traced. These include a relaxation of the pressure to innovate, building on the existing achievements, and turning to the heritage of the past. These developments are present in the work of Luciano Berio, György Ligeti, Krzysztof Penderecki, Henryk Mikołaj Górecki, Arvo Pärt, and others.

The style developed by Silvestrov, which brought him world recognition, was identified in different ways – he was called a postmodernist, a neo-romantic, a representative of the direction of new simplicity, etc. The composer himself does not agree with these labels. When explaining his ideas and aspirations, he often refers to the term “metaphorical style.” One can grasp this phenomenon from Sylvestrov’s own explanations:

“A metaphor is a transfer of meaning; it arises as a result of the inability of one phenomenon to represent another in equal terms.” 5

“Any successful text has a symbolic meaning. The language that transmits this text is important, but the essence of the thing is not contained merely in the language. Language here allows to express something that exists beyond words. This is metaphoricity, metalanguage.”6

“The metaphorical aspect in my piece Music in the Old Style7 lies in my aspiration to avoid stylization by means of certain compositional and peformance techniques. The piece is on the verge of stylization, yet I tried to achieve an effect allegory rather than a direct reference to a text.”8

Metaphorical style, therefore, aims to point to a phenomenon, which is indirectly related to certain musical means, to achieve many layers of meaning and allow for multiple interpretations. This idea can be implemented by triggering the cultural memory, rethinking and reinterpreting the means that accumulated and preserved this memory. Therefore, his music includes a return to the tonal system, and consonance of harmony and melody. Melody needs a particular mention, since its revival is connected with the ideas that are relevant for Silvestrov’s work, as I have previously noted. The composer addresses the listener and contemplates the role of music in human life of previous époques; music is a way of communication, lyrical and intimate expression. Melody, therefore, becomes of primary importance, because it is singable, memorable, it can be internalized, together with its entire spectrum of diverse feelings. The interpretation of such music requires a new approach to performance, in which a virtuoso concert style doesn’t work as it can destroy all the nuances, emphasizing only the standard compositional methods. Metaphorical music is the music of recollections, an allusion, spoken sotto voce. This is where Silvestrov’s “micro-technique” comes from, along with specific demands for performers – he envisions an intimate, home-style manner of sound production. The composer’s scores are full of instructions regarding tempos, dynamics and microdynamic changes, methods of sound production, the nature of performance, etc.

In Silvestrov’s work, this style was developed over time, as its first examples appeared in Drama for violin, cello and piano (1970–71), Meditation for cello and chamber orchestra (1972), Cantata for soprano and chamber orchestra based on poems by Fyodor Tyutchev and Alexander Blok (1973) and other compositions around that time. They still have a strong connection to the preceding avant-garde period, primarily in terms of expressive means – Silvestrov uses elements of instrumental theater (most notably in Drama), aleatoric technique, extended instrumental techniques, pointillist and texture and sonoristics. Yet in the works of metaphorical style, along with abovementioned techniques, references to music of the past begin to emerge, such as classical cadences, deceptive cadences that define romantic harmony, expressive melodic lines with sequences, differentiation of textures into a melodic line and an accompaniment, etc. Such elements can definitely be interpreted as a metaphor of a certain musical ideal, which emerges from the chaos of dissonances and noises.

One of the works that best represents the characteristic features of the metaphorical style is Silent Songs – a vocal cycle for baritone (or soprano) and piano (1974–77), setting the texts by classical poets. It already contains all the features that will become characteristic of Sylvestrov’s musical utterances: 1) a melodic lines that seems to give voice to speech, at times fragmentary, at times long-lasting, with its emotional ups and downs – “singing-as-breathing”9; 2) the multi-layered texture of the piano part with some stretched-out sounds, which creates the impression of echoes and prolonged harmonies (this type of texture will become characteristic of the composer’s orchestral works); 3) tonal harmony of different kinds with an emphasis on late romanticism. The score is replete with numerous remarks and instructions to performers, aimed at achieving the required quality of sound: “All songs should be sung very quietly, with tender, transparent and bright voice, with precision, despite the rubato in dynamics and tempo, with restraint and no psychologism.”10 This kind of new approach to sound certainly mesmerized the listeners at the premiere. According to my observations, it still continues to impress today.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Silvestrov started travelling to European countries (especially to Germany), where he worked on new compositions, studied the works of his colleagues, and presented his own. Yet he would always return to Kyiv.

Bagatelles

The beginning of the 21st century marks a new period in Silvestrov’s work – the creation of miniature pieces called bagatelles. As the composer recalls, “from 2000, he began writing small pieces – bagatelles – that demonstrated alertness to grasping an ephemeral gift of a fleeting moment. (…) The precious quality of bagatelles is the lack of ideological burden, and their origin in a spontaneity of a creative act.”11 The sound world of bagatelles comes from the lineage of the metaphorical style; they seem to prolong that single beautiful moment, which Silvestrov captured in the 1970s and has been enjoying for almost half a century. The composer has created hundreds of such miniatures and often records his own performances of bagatelles on the piano. Silvestrov often gives self-made CDs with bagatelles, waltzes, and songs to his friends.

Despite all the obvious differences, however, these works come from the lineage of bagatelles, from suspended moments of fleeting beauty.

From the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Silvestrov evacuated to Germany, where he currently lives. He continues his usual activities – gives interviews, participates in concerts, attends performances of his own works. (One of the major events in honor of the composer’s 85th birthday was the Ukrainian festival “Kyiv Bouquet Stage” in Oxford, in the fall of 2022.) 12 Amidst all these activities, he nevertheless continues composing bagatelles…

Translated by: Oksana Nesterenko

Text originally published in Polish in “Ruch Muzyczny” biweekly, thank you for permission for the reprint and translation.

Valentyn Silvestrov bibliography (April 2023)

- Gillies, Richard Louis, Valentin Silvestrov And Putin’s War in Ukraine, “Tempo” No. 77 (304) 7–20, 2023.

- Nesterenko, Oksana. A Forbidden Fruit? Religion, Spirituality and Music in the USSR Before Its Fall (1964–1991), Ph.D. diss., Stony Brook University, 2021: 179-203.

- Schmelz, Peter J. Sonic Overload: Alfred Schnittke, Valentin Silvestrov, and Polystylism in the Late USSR. Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Schmelz, Peter J. Such Freedom, If Only Musical: Unofficial Soviet Music During the Thaw, Oxford University Press, 2009: 257-269.

- Schmelz, Peter J. Valentin Silvestrov and the Echoes of Music History. “The Journal of Musicology”, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Spring 2014): 231-271.

- Wilson, Samuel. Valentin Silvestrov and the symphonic monument in ruins. in: Transformations of Musical Modernism, edited by Erling E. Guldbrandsen and Julian Johnson, 201-220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

V. Silvestrov Muzyka — eto peniye mira o samom sebe… Sokrovenny razgovory i vzglyady so storony: Besedy, stati, pisma, ed. M. Nesteva, Kiyv 2004, pp. 66–67. All translations by O. Nesterenko. ↩

Now — National Music Academy of Ukraine. ↩

N. Varenik, V. Silvestrov, Під час інавгурації Віктора Ющенка вперше пролунала хороша класика, ZN, 2006. Вип. 21 ↩

V. Silvestrov, Muzika…, pp. 89–90. ↩

Ibidem, p. 105. ↩

Ibidem, p. 135. ↩

The piano cycle Music in the Old Style was composed in 1973. It includes four movements: Morning Music, Evening Music, Contemplation, and Dedication, where Silvestrov alludes to the Baroque, Classical ans early Romantic styles. ↩

V. Silvestrov, Muzika…, p. 117. ↩

Silvestrov’s own expression. ↩

Silvestrov, quoted according to the composer’s comment to the score of Silent Songs, published by Sovetskii Kompozitor in Moscow (1985). The original version with comments belonged to Professor of Musicology of Kyiv Conservatory Nina Herasymova-Persydska (1927–2020). It is currently housed in the private archive of the Persidsky family. ↩

V. Silvestrov, Muzika…, p. 198. ↩

I. Oliynik, Українська музика в Оксфорді: The magic is going to start ↩