fascies firestarter kit

Face it and voice it

When you close your eyes to obvious acts of violence and evil, you only allow it to grow says Ukrainian composer Alla Zagaykevych, who believes in electronic music as a radical form of freedom. Reportage from the event Antifascism – Electronic music from worlds on fire in Lund, Sweden.

photo: Sanne Krogh Groth

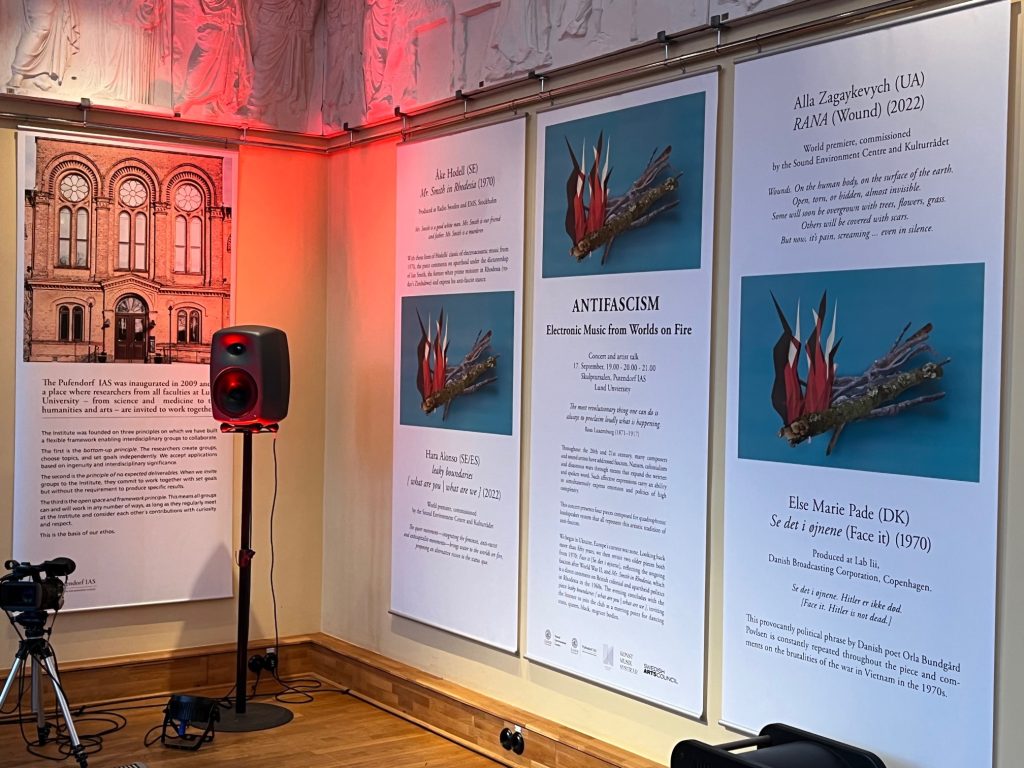

Garlanded with copies of the Parthenon frieze, the Sculpture Hall of Lund Pufendorf IAS welcomes a dense crowd softly illuminated with pink and warm lights. Everyone sits quietly, while the pleasantness of the atmosphere merges with an oneiric sound fading in. Soon, the dreamy soundscape becomes sinister, commencing a concert of strongly engaged political music pieces.

Curated by Sanne Krogh Groth, Katja Heldt and Staffan Storm in occasion of the Night of Culture 2022, Antifascism – Electronic music from worlds on fire greets us with a quote from Rosa Luxemburg: »The most revolutionary thing one can do is always to proclaim loudly what is happening«. The quadrophonic loudspeaker system surrounding us indeed plays four compositions that could not speak up more powerfully and clearly. Whether in the tradition of the ‘70s or recently commissioned for the event, strong voices emerge through the works of predominantly female composers. Sometimes they are highlighted by neat cut and paste techniques, sometimes they are barely traceable, touching different issues with various approaches, thus unfolding the diverse sensibilities that compound post-war antifascism yesterday and today from a rather intersectional perspective.

Beauty alone won’t save the world

The premiere RANA (Wound), composed in Kyiv by Alla Zagaykevych by commission of the Sound Environment Centre (under Lund’s University) and the Swedish Arts Council in collaboration with Konstmusiksystrar, inaugurates the evening by addressing the current war in her home country. With its initial evocative tones, I plunge in layers of anguish and restlessness, attacks, and counterattacks. In the unfolding of the piece, dense and viscous, distorted raid signals, slashing sounds, and metallic voices blend in a gloomy event of uncertain yet tense inner dynamics. The abstract electronic piece includes samples of the bandura, a traditional plucked stringed instrument whose use was banned in the 19th century under Imperial Russia and punished with death under Stalin. Here, Zagaykevych reclaims it by playing only its bass stings and with a bow, manipulating its melody into a razor-cut metallic sound.

After the attack, the wounds left are voiced by traditional Ukrainian singing, barely recognizable in the thick soundscape that pervades the hall and obscurely evaporates behind my back in waves. The atmospheric nature of the piece does neither resolve in a salvific or conciliating end, nor does it declare defeat. Rather, it leaves me in medias res in an unresolved feeling of counteraction, damage, and suspension. Contrarily to what Dostoevsky’s prince Myshkin said, beauty alone won’t save the world, it requires a voice and reaction.

Mr. Smith and a marching drum

A voice barges through the dry announcement »Hitler is not dead«, opening the sound collage Face it (Se det i øjnene, 1970) of Else Marie Pade with a quote of poet Orla Povlsen. Its rhythmic and blunt shift is piercing yet numbing while I absorb its pounding monotony punctuated by the flat sound of a marching drum and begin to recall all the Hitlers inhabiting our world. The sentence’s evil banality gradually reveals its violence with bursts of hysterical speeches of the Führer, confronting me with a verbal violence that surpasses the Vietnam war to which the piece refers, and reminding us listeners of the relevance of antifascism today.

Equally direct are the political statements of Swedish composer Åke Hodell in Mr. Smith in Rhodesia (1970), where a choir of children repeats after the imparted slogans favouring white supremacist and former leader of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) Ian Smith. In the fashion of its times – and not too dissimilarly from the sampling techniques used by Pade– the hypnotic repetitions are revived by variations that, sometimes voicing whispers and shouts, sometimes playing Zimbabwean music, suggest the emergence of opposition and critique. In fact, Hodell guides us through the process of African people’s self-recognition as owners of their culture and land, marked by the triumphal verdict of the children’s choir: »Mr. Smith is a murderer«.

A philosophy of care

Inspired by Hodell’s straightforward use of collages and montages, Swedish-Spanish composer Hara Alonso deploys raw fragments of phone recordings, while mitigating the bluntness of the technique with lo-fi and affective energy. In Leaky boundaries [what are you | what are we], the voices of trans and queer people discuss empathy and intersectional awareness. I follow them, jumping from their intimate kitchen discussions to the streets animated by the crowd at Stockholm Pride and ultimately to the beats of a club. There is something very powerful in these voices exposing themselves so genuinely, radically situated and thus operating not only as a choral tool of liberation, but also as a sign of corporeal presence, readdressing the centrality of the body as a space of political battle and affective connection. In Alonso’s piece these voices suggest the adoption of a philosophy of care and intersectional solidarity to recognize the leaky boundaries that regulate and unite human relationships as a tool against facets of contemporary fascism.

We get an idea what antifascism means – not only in the past, but also in a contemporary global context affected by injustices, conflicts, and the looming presence of right-wing groups in the political landscape. The concert acquires particular significance against the backdrop of the rise of Sweden’s major right-wing party as well as the rise of a post-fascist government in Italy and analogous phenomena on a global scale.

Culture is not an object, but a subject

Aware of Alla Zagaykevych’s pioneering work as the founder of the first Ukrainian electroacoustic music studio, I was delighted to meet such a woman. Some extracts from our discussion follow below.

Alla, how do you position yourself as a female composer in Ukraine?

Positioning myself as an artist, I acknowledge my responsibility as such and thus, even though the Russians now are killing us, I need to continue the creative process of teaching, learning, making music, organizing cultural events. I also keep working as a researcher, since musicology in the frame of electroacoustic music in Ukraine is not developed enough: my aim is to educate and provoke my fellows to explore and produce more Ukrainian electroacoustic music without shame.

How did these responsibilities and functions in society change with the war? How are they related to your sense of identity as Ukrainian, maybe even in terms of retrospective historical recognition?

They have acquired more meaning, but in more practical terms. For instance, we never had a real archive of Ukrainian electroacoustic music, so very quickly I tried to gather all the possible material to save it in digital archival structures – we are already disseminating it in European concerts. To this, I added the documents and annotations from my personal archive to create textual information. Also, me and others started to take care and consolidate those international cultural relations that before were never taken seriously, that is: to acknowledge our value and focus more actively in communicating with other countries. This has promoted a change in internal forms of communication between musicians, artists, and institutions: with the war, we have become closer to each other, more horizontal and acquired subjectivity: some of us started to realize how culture is not an object, but a subject. Our identity changed also retrospectively in recognizing past cultural figures that had been suppressed by Russia or have been rehabilitated as part of their culture instead of the Ukrainian one.

If I understand correctly, this deliberate act of aggression helped you to realize your value, and to get rid of your complex of inferiority. Archive is one of the most important tools to preserve and create memory, and thus to shape a certain identity. How did this recognition of identity happen, especially retrospectively?

We as artists have always believed that art and culture are separate worlds, and artists like Tchaikovsky are not Russian, but universal ones. And this is a big mistake because Tchaikovsky represents the imperialistic culture of Russia as well. Art and beauty do not save the world, you need to critically discern between good intentions and what is simply evil, a white and black point at the extremes of the nuances. When you close your eyes to obvious acts of violence and evil, you only allow it to grow, which is what most of the Russian intellectuals have been doing.

I can recognize these dynamics in my own country in the past century. You pointed out the importance of recognizing and contextualizing certain phenomena in their locality instead of abstractly universalizing them. Can you tell something more about your research activities on traditional Ukrainian music?

While studying at the conservatory, I went on an expedition to do research on folkloric music. It blew away my mind as much as the post-war avant-garde of the ‘60s did when it renewed European music and cleaned it up from the residues of fascist elements. I was not attracted by folkloric music for only aesthetic reasons, but for its ‘authenticity’ [traditional ‘white singing’ style] and situatedness. More closely related to natural rhythm, and basic sociocultural dynamics, folklore can be a source for artists for different perspectives in showing how culture moves along with nature. Folklore, in fact, is anything than sweet: it can be very aggressive and visceral.

In many of your compositions you use notes from the field of traditional instruments and rework them, reaching a rather high level of abstraction. It seems to me that your creative practice makes use also of your activity as a researcher. Do your works play a role in your research activity in terms of re-development or reflection?

I don’t do specific research work with folklore expedition recordings. It’s more of a creative practice. Of course, it involves testing technologies, looking for specific means, but it is the usual practice of the contemporary composer who works with technologies. If I had more time, I would rather research the practice of electronic music as part of academic musical culture. How is contemporary musical thinking evolving? How is it affected by technology?

Can you tell a bit about your work RANA and where the ideas and compositional aspects come from?

When I received the commission, I was wondering what was exactly haunting me: I was often dreaming that I was walking in my neighbourhood in the nature where shells had fallen; suddenly I realize that I am in a crater made by a shell and am afraid that there could be more mines. I saw an aerial picture of the Ukrainian land hit by shells, and it looked like a body covered with wounds: wounds on the body and on the earth are the same, everything is wounded there. This is what I decided to tell in my piece, although the dreams didn’t stop. For the composition, I used songs from the area of Polesia and samples of a bandura played with a bow to confer it a bright ringing sound. For me it was important that it had a rather high timbre and an ‘authentic’ form of music as reaction and quick response to pain. Electronic music is a radical form of freedom and not only because it allows me to use sounds that I create by myself and sample them, but also in combination with folklore, which is very close to electronic music to me. They are both a pilgrimage in between traditions where you can trace your own path as you like it, instinctively, even without musical education, as in the case of folklore songs.«

Thank you for sharing with me these thoughts, that stem from a personal sensibility while drawing to highly political reflections. To reconnect with my first questions, I would like to ask you: what does it mean to be anti-fascist today? What can artists and musicians do, and what can we all do, in your opinion?

To me, anti-fascism means critical thinking, active and responsible citizenship. First and foremost for artists. The art of the twentieth century accumulated a very rich experience of high art. In theatre, literature, and music. Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Vonnegut, Czeslaw Milosz and Paul Celan, Bernd-Alois Zimmermann and Olivier Messiaen… I think the big opera institutions, theatres… philharmonics could do much more nowadays… at least express their position and not cooperate with artists for whom “art is beyond politics”.

Do you have a message for our readers?

Some old lyrical song from Polissya or Poltava?

***

The white voice mentioned in the interview, typical of Ukrainian pagan singing, is performed with open throat at free volume and is thus referred to as ‘controlled screaming’. Throughout the concert, voices have been used as sonic material by all the presented composers, who also modulated their vocal denunciations. While musicians and artists cannot end fascism through political means, they can teach us the importance of voicing out its old and new forms of oppressions and injustices rather than silently observing and normalizing them – whether they lead to xenophobia, sexism, racism, transphobia, capitalistic exploitation, or even schizo-fascism, defined by Eastern Europe historian Timothy Snyder as the phenomena in which people or governments refer to others as fascist, while acting themselves in a fascist-like manner. They can remind us again of the highly political nature of giving space to other voices and to listen to them with openness and empathy, acknowledging that the boundaries between us are porous or, as Alonso puts it, leaky.

Giada Dalla Bontà

Text originally published at “Seismograf” journal, original Danish version here.

The events took place 17 Septembre during Kulturnatten Lund 2022 and was organized by Lund University’s Sound Environment Centre in collaboration with Pufendorf IAS, Inter Arts Centre, Kulturrådet and Konstmusiksystrar.