Vocal Techniques Assorted Chocolates

Between voice, text and sound

My path to electronics

As my interest in electronic music continued to grow, I began using simple programmes that allowed for basic transformations of recorded sounds. The methods already used by the pioneers of electronic and concrete music include cutting sounds, editing, as well as changing the playback speed of audio material. Of all these techniques, I was particularly fascinated by editing, due to its strong similarity to instrumental composition. Different sound elements can be combined with each other simultaneously. Cutting and editing are powerful tools used to create and simulate even media contexts that are difficult to imagine in reality. For example, it is almost impossible to understand a whisper in the noisy Kiev metro, but with the right software, such a situation can be simultated. If we add a delay effect to this whisper, a metaphorical soundscape is created.

I found it particularly exciting to create sound gestures using different voices. For example, a word can be started by a child and finished by an adult, or parts of words and sentences can be reproduced in different forms of expression. On this basis, in 2016, I created my electronic work ihearyou, in which the central element was precisely sound gestures. A moment later, I discovered the looper, a tool that repeats a specific sound, creating the impression of a ready-made ostinato or texture onto which new layers of material can be superimposed. This method resulted in more complex and dense structures. In 2017, I composed the piece Doyouhearme? for voice and looper, superimposing different phonetic layers.1

My interest in voice developed in parallel with the development of basic techniques for creating electronic music and vice versa, which made it easier for me to enter the world of electronic music through the use of vocal recordings. In the following work, I will attempt to summarise the relationship between the vocal and electronic components in my music. I would also like to present my compositional method of creating vocal music, in which the voice is perceived not only as a musical instrument conveying text, but also as an integral part of the human body. The focus is on various aspects of vocal composition that take into account the subtle nuances of the voice as a physiological element. This includes the different types of information it can convey, as well as human behaviour that influences it. By exploring the potential of the voice from these perspectives, I am able to interpret material for vocal works in a variety of ways and adapt my approach accordingly. I also pay particular attention to text – as the most common form of information conveyed vocally – and its transformation, which can also be influenced by the overall condition of the vocal apparatus and the human body.

The above-mentioned aspects significantly translate into the dramaturgy of the piece and its overall concept. Based on …au ciel enflammée for soprano and electronics from 2023, I will explain how working with the text, the performer, her voice, hearing and body influences the dramaturgy of the piece, its idea and concept, and how this influenced the final result.

The role of text and the creation of language

The piece …au ciel enflammée is my first attempt to incorporate existing text into my work with the voice. This addition was quite a big step for me, especially after a long period of experimenting with different types of vocal sound information. Before working with text, I was held back by the observation that when spoken, it is in itself already a ready-made semantic sound composition that must be taken into account and on which one is dependent.

The voice, like an instrument, is difficult to understand solely as a medium between the performer and the listener, because it is part of the singer’s body. If one could imagine an intermediary instance alongside the voice, it would have to be the text (sung or spoken), but of course the reverse is also true – the voice can be understood as an intermediary of the text. For this reason, it was particularly important for my work to establish a clearly defined relationship between text, voice and composition from the very beginning, in order to understand how the sound of the text and its meaning would influence my composition.

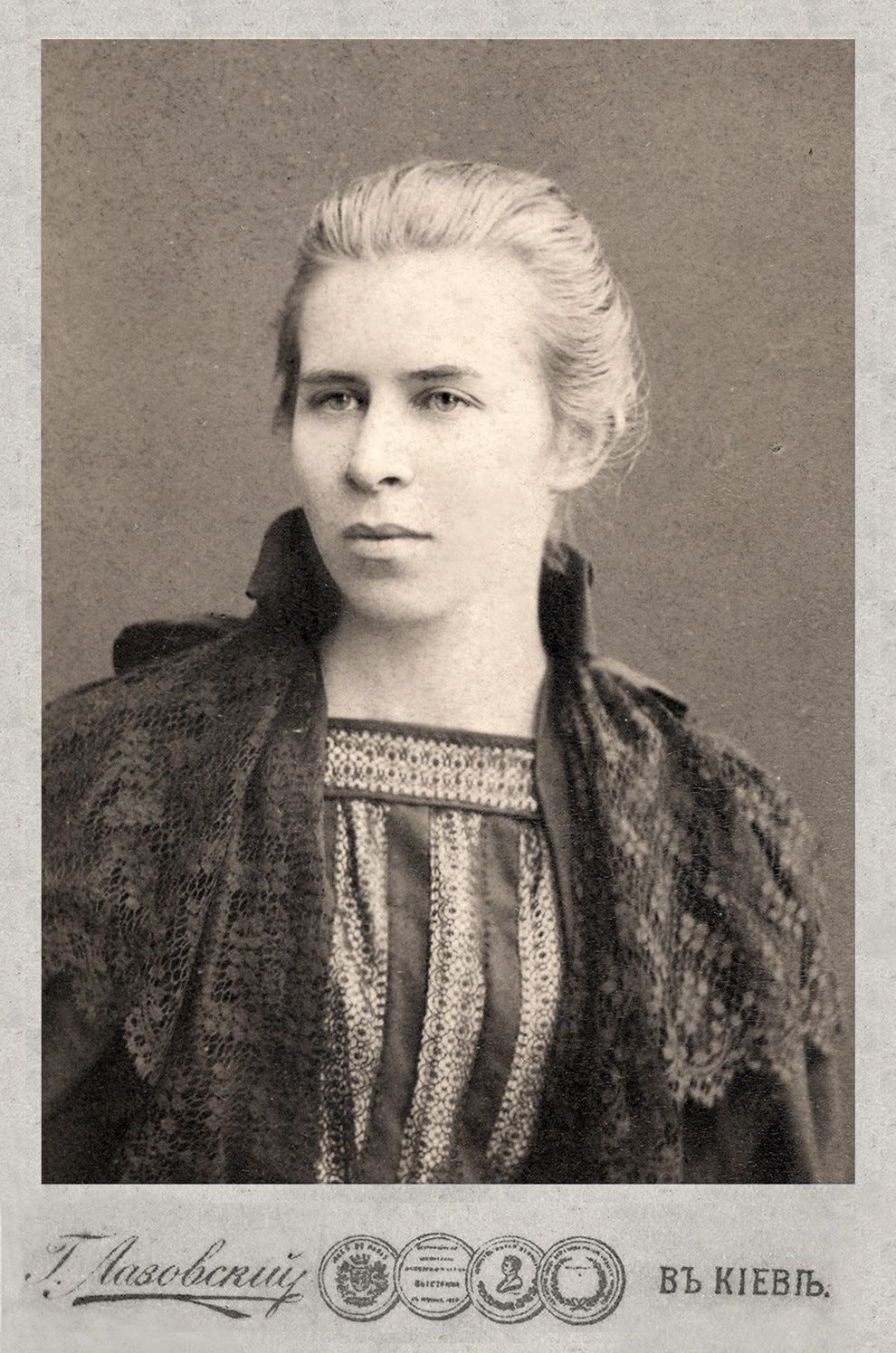

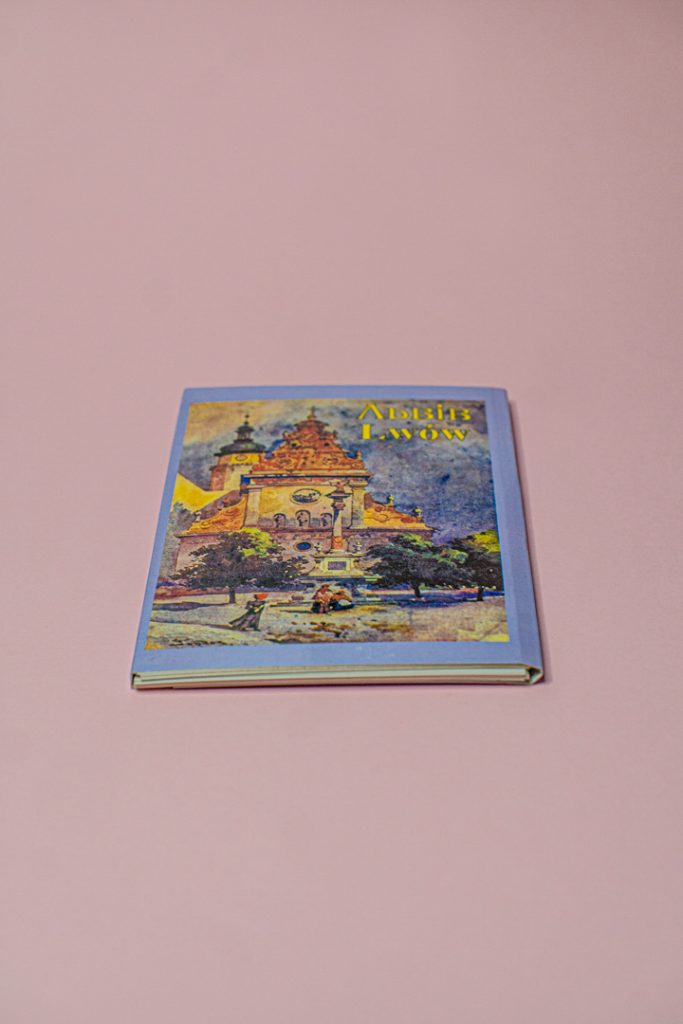

From early childhood, I was fascinated by the work of the poet Lesya Ukrainka (1871–1913), whose works often accompanied me. When I was at school, the characters from her play The Forest Song (Лісова пісня) inspired me to create my first piano miniatures. Ukrainka’s poetry is very natural to me, her ideas and feelings correspond to mine. I have also known the poem Contra Spem Spero (1890), which I chose for ...au ciel enflammée, since early childhood:

Away, dark thoughts, you autumn clouds!

A golden spring is here!

Shall it be thus in sorrow and in lamentation

That my youthful years pass away?No, through all my tears I still shall laugh,

Sing songs despite my troubles;

Have hope despite all odds,

I want to live! Away, you sorrowful thoughts!On this poor, indigent ground

I shall sow flowers of flowing colors;

I shall sow flowers even amidst the frost,

And water them with my bitter tears.And from those burning tears will melt

The frozen crust, so hard and strong,

Perhaps the flowers will bloom and

Bring about for me a joyous spring.Unto a winding, flinty mountain

Shall I bear my weighty stone,

Yet, even bearing such a crushing weight,

Will I sing a joyful song.Throughout a lasting night of darkness

Ne’er shall I rest my own eyes,

Always searching for the guiding star,

The bright empress of the dark night skies.I shall not allow my heart to fall sleep,

Though gloom and misery envelop me,

Despite my certain feelings

That death is beating at my breast.Death will settle heavily on that breast,

The snow covered by a cruel haze,

But fierce shall beat my little heart,

And maybe, with its ferocity, overcome death.Yes, I will laugh despite my tears,

I’ll sing out songs amidst my misfortunes;

I’ll have hope despite all odds,

I will live! Away, you sorrowful thoughts!2

Poetry became a kind of universe for me, where I was sure I could remain myself and stick to my ideas, which is closely related to the emotional expression of poetry. Since the sound aspect already existed in this case, I first had to consider how far I could go in transforming the text.

While creating the piece, I was fortunate to work at IRCAM in Paris from October 2022 to September 2023. There, I had access to a recording studio where I could ask the singer Viktoriia Vitrenko to try out many variations, which I could then record. The starting point for our work was reading the text. I made a specific list of styles in which I wanted the text to be read (e.g. pronouncing only consonants/vowels, simulating different emotions, etc.). One of the most interesting transformations was a method in which the spoken phrase was recorded and immediately played back backwards. The singer then tried to imitate the ‘reversed’ sound, which was also recorded and played backwards. As a result of this process, the original words were still recognisable, but they were distorted and pronounced in a strange way.

This change in language was not ultimately used in the song, but it became a trigger for defining the idea and concept, as well as the dramaturgy. An image emerged of a character who regained the ability to speak after being inhibited by various blocks such as trauma, shock or a state of dormancy. In this way, the text and its meaning became the driving force behind the basic idea of the play’s dramaturgy: the revival of voice and language, the attempt to say something, and ultimately healing through poetry. Due to the fact that I worked at IRCAM, as well as my environment, I decided to use the French translation of a poem by Henri Abril, published under the title L’espérance3.

As a result, the use of two languages allowed for a more varied sound of the text and additional control over its recognisability and comprehensibility. I had often worked with the voice as an instrument before, so it was crucial for me to pay attention to the moments when the sounds of the voice end and the words begin, to listen to where the boundary lies between understanding and misunderstanding, between the perception of individual words and the construction of poetry.

Musical structure and dramaturgy

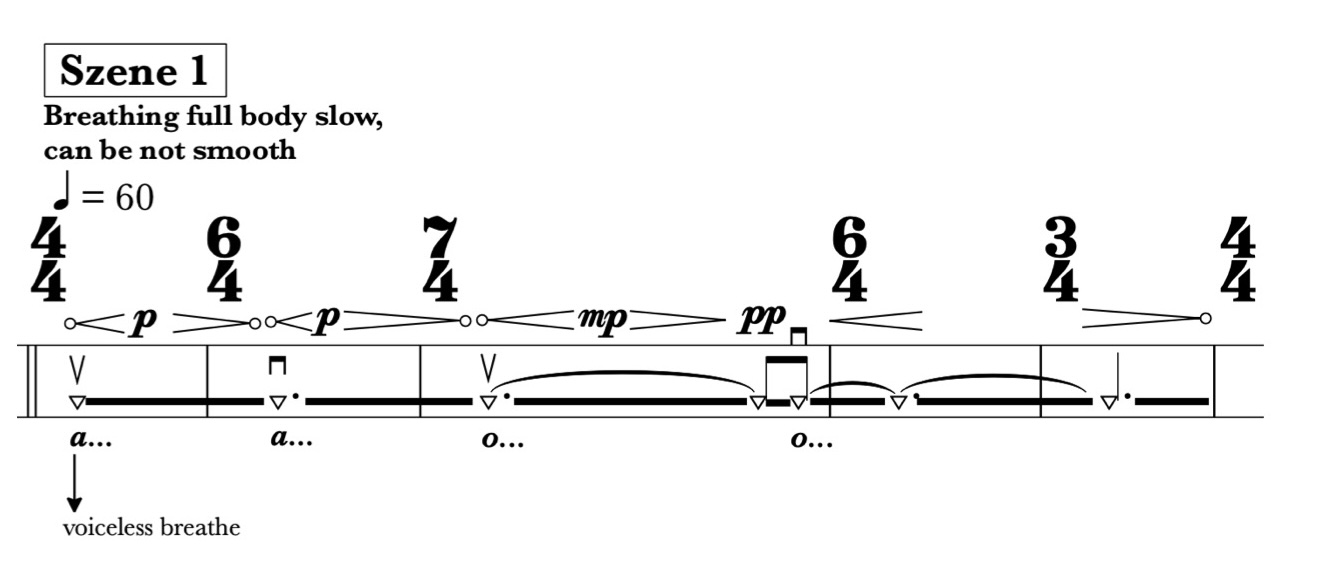

The work is divided into eight scenes. Each of them represents a stage of transition from the initial state of silence to the utterance of text. The introduction and the first two scenes reflect a character who is, in a sense, blocked on stage. In the next three scenes, the core of the text is already present, but it is not yet fully pronounced, while the proportion of sounds in the structure increases. Finally, the last three scenes lead to clear singing and complete recitation of the poem. The first part is an electronic intro with fragmented, punctual sounds that gradually evoke a feeling of cold emptiness in the audience. The first element is introduced into this emptiness – a singing voice. Starting from the idea of progression between silence and articulated poetry, I established the initial ‘point of silence’. Just consider the state of a soprano: what does she do when she is not singing? She breathes. Breath, which is the basis of the voice, is also present in silence and becomes the main element of the first scene:

This basic and expanded material is accompanied by slightly more active and variable breathing, coughing, and almost panicky shortness of breath in the form of a recorded sound. Their volume is activated by the singer’s breath signal to the microphone, through micro-events in prolonged breathing. An additional musical background in this scene is the lingering sound that remains after the intro.

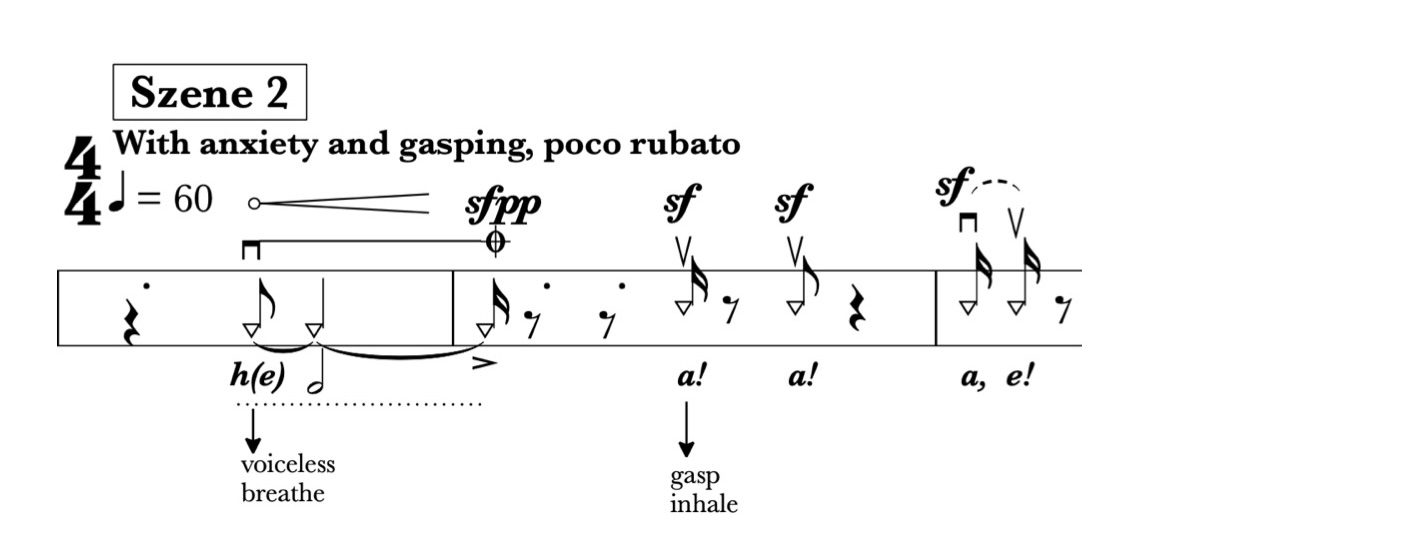

Suddenly, the soprano’s breath takes on the restless mood of the recording, and in scene 2 presented below, this material undergoes rhythmic transformations: short inhalations and exhalations on different formants, which become a kind of breathing passages, throat beats and single, sudden sounds:

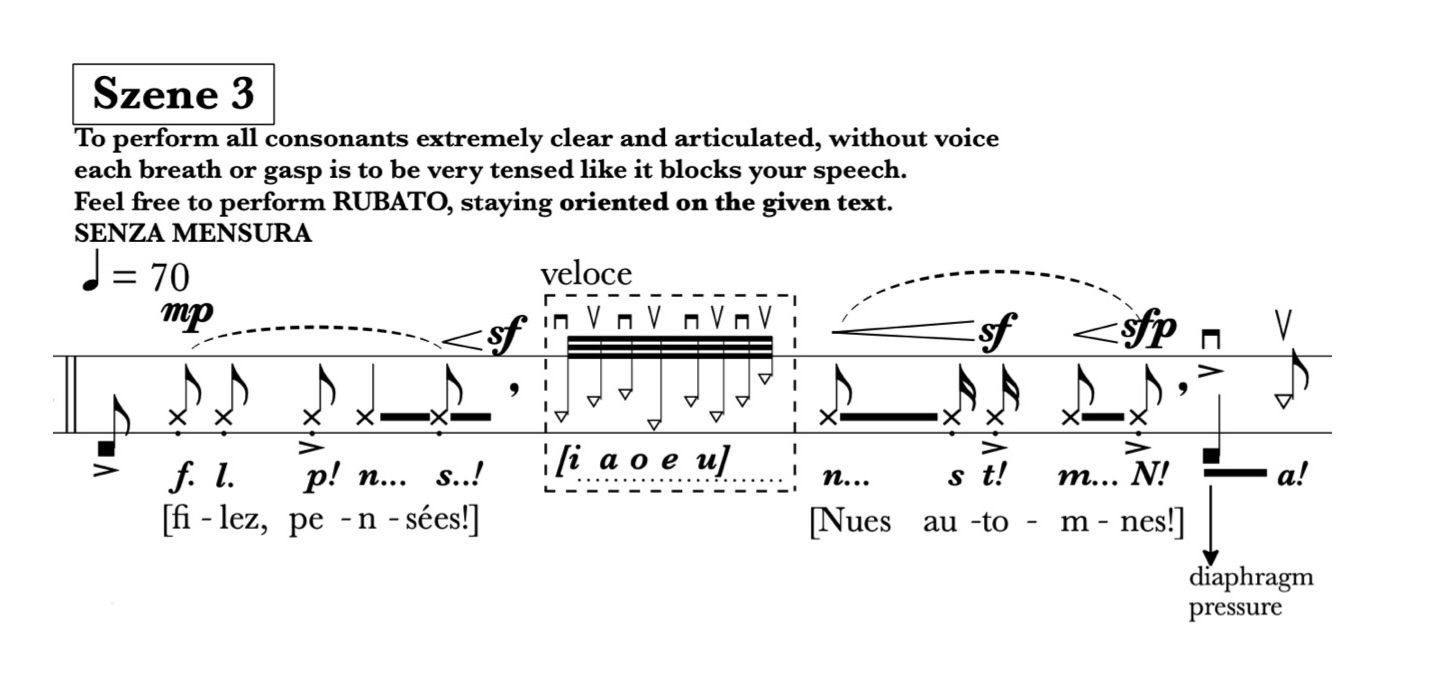

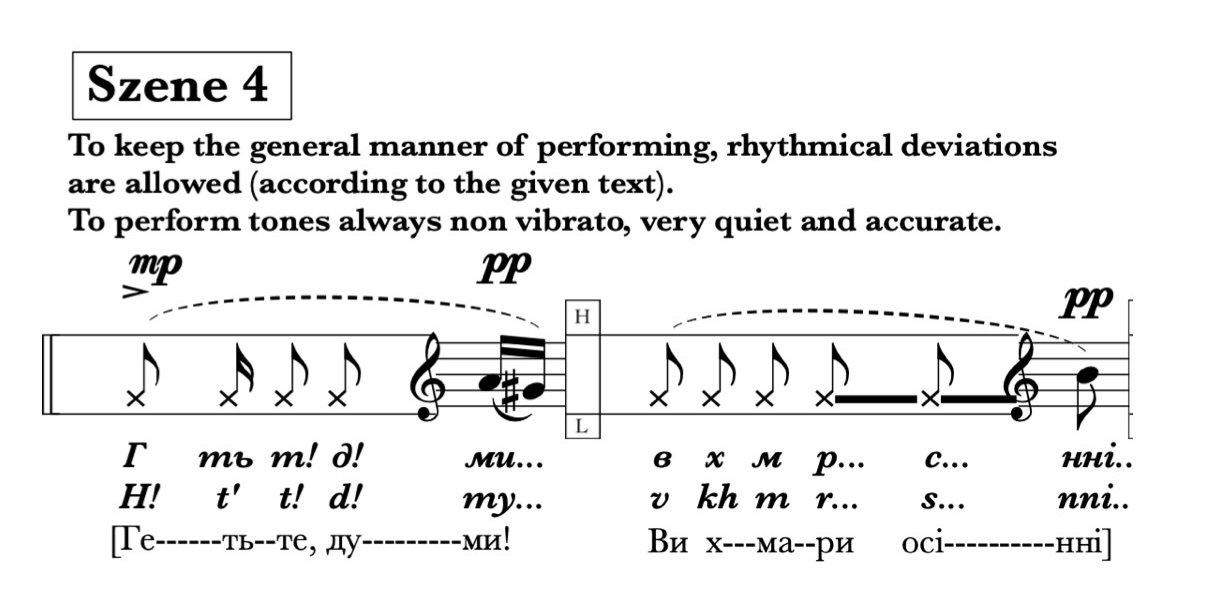

The elements presented above are intended to prepare the listener for the appearance in scene 3 of a new series of noises and sound colours, which is defined by the poem itself:

This is accompanied by short samples: abstract fragments of coughing, breathlessness, screaming, whispering, and vibrating sounds in the background. Another important symbolic element, from the point of view of the concept of the work, are the sounds of writing. Although this is an abstract and sonic embodiment of the text, it is nevertheless an important form of its preservation. I decided not to ignore it and to add the sounds of writing to the collection of figures in my work. A significant part of the electronic part in this piece is based on the rhythmic sounds of writing.

In scene 4, we can observe a continuation of the previous process. Here, I decided to add the same text, but in Ukrainian, and to give it due attention for several reasons. The sound models of languages differ, so this turned out to be a way to diversify the phonetic sound image from the previous section and to slow down the perception of words that could become understandable to the listener here. In addition, the transition to Ukrainian text in this section facilitated the process of vocalising individual syllables. In my opinion, the use of my native language ensured an organic and light beginning to the gradual vocalisation of this material.

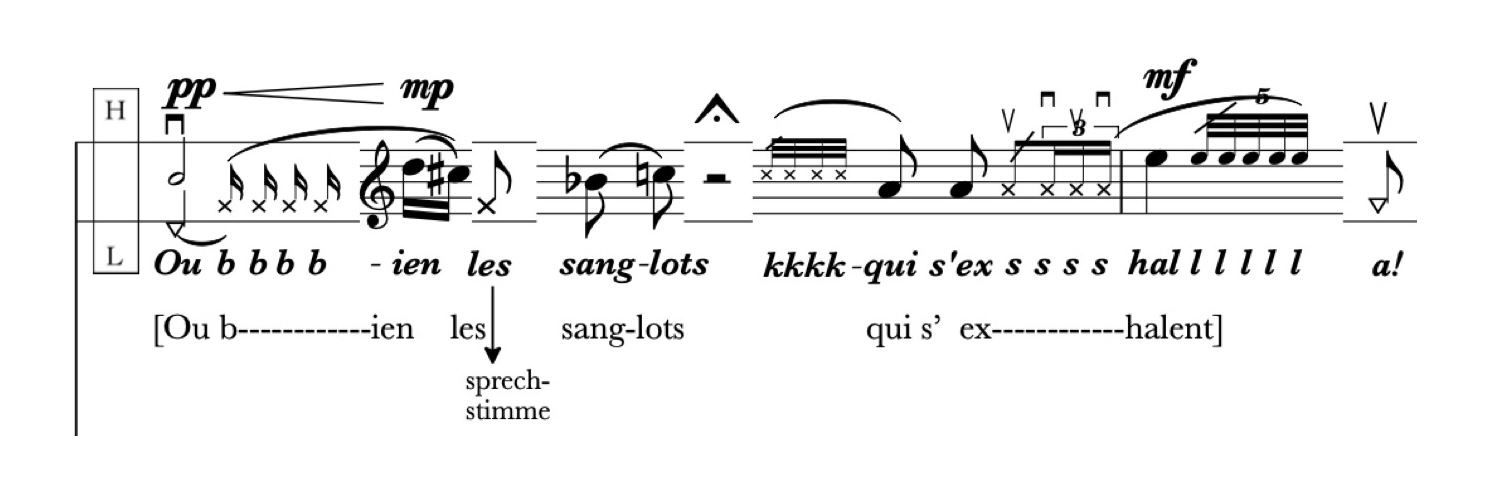

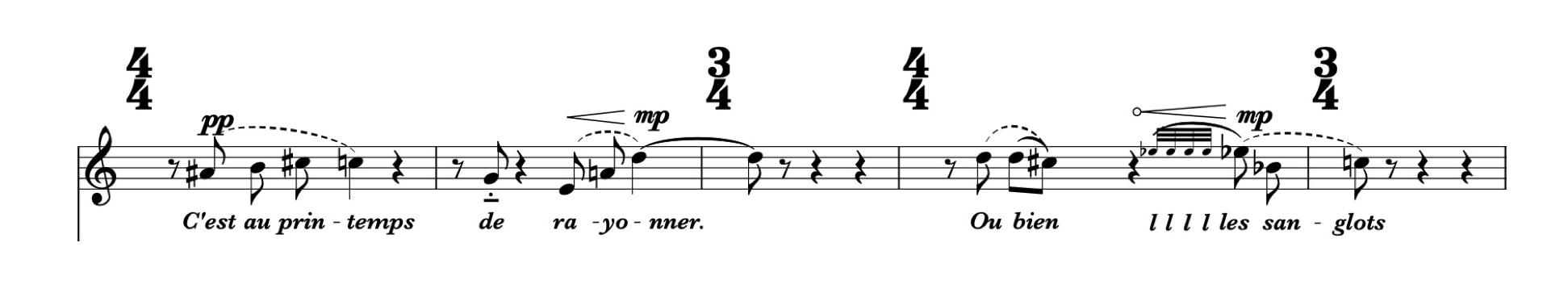

In scene 5, I return to the French version, reinforcing individual syllables with notes from the melody of the next song, which will be sung in its entirety in scene 6. The piece seems complete here, but it is not yet properly expressed, because the individual motifs and phrases are uttered in an interrupted, stuttering manner, as if they were inhibited by an outburst of emotion or crying, which initially blocks any clear articulation. This is expressed by means of small rhythmic sounds before and after the motifs, which accompany every second or third word:

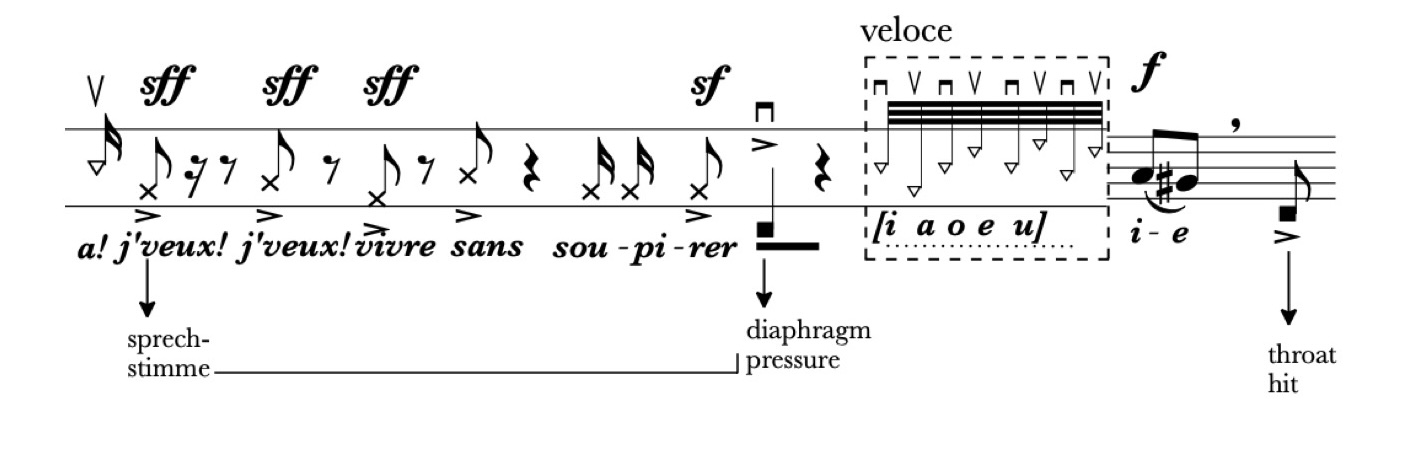

It is also worth noting a small deviation from the structure of the text at the boundary between the two scenes. Scene 5 marks the moment when the text and its idea are already sufficiently understandable, which gives me reason to believe that the main character has finally regained her speech. For me personally, this happens at the moment when she finally speaks – not singing, but emotionally shouting the phrase ‘j’veux!’ several times and formulating the sentence ‘vivre sans soupirer!’ [‘I want… to live without sighing’]:

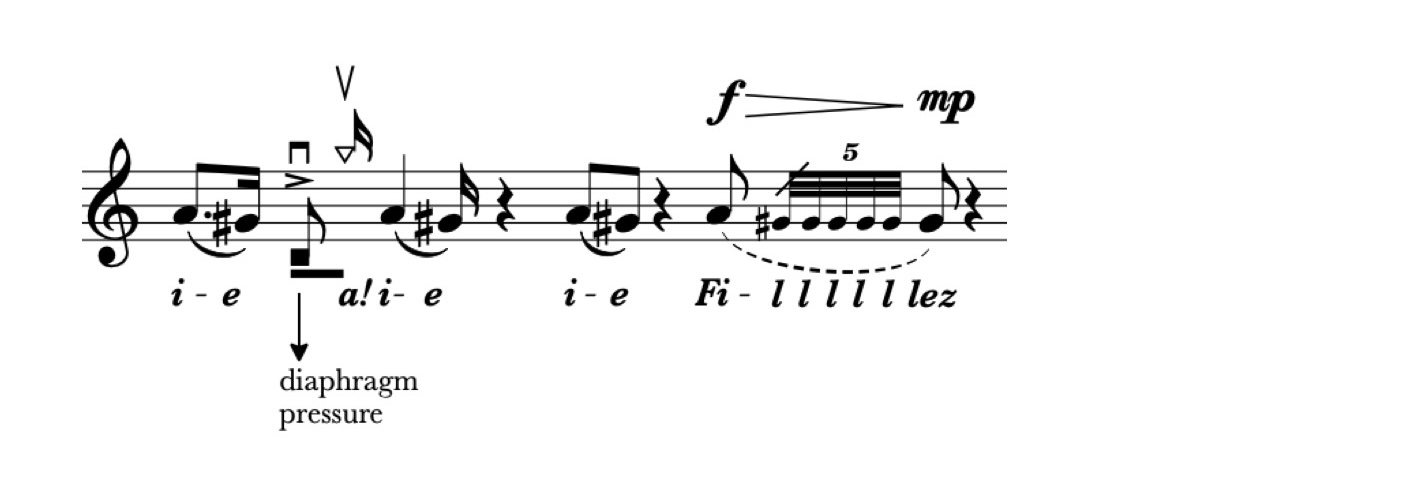

This is followed by the singing of the first motif of the song (a minor second, a–g sharp) on the vowels of the word ‘Filez!’ [Away!]. For me, this moment became the final round in the game of comprehensibility and incomprehensibility of words:

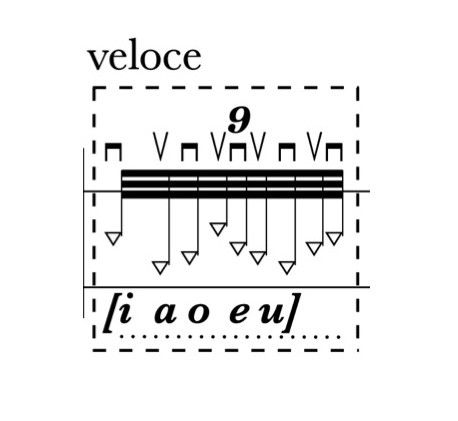

Before I move on to the analysis of scene 6, I would like to draw attention to additional structural details in the overall course of scenes 3, 4 and 5. Of course, I did not want to reveal all my cards at once, so I tried to hide this structure not only behind the sound material, but also behind individual elements of breathing. In addition to the text, there are often stable ‘breathing transitions’ – marked veloce and performed on various formants – as well as single sighs, laryngeal strikes and intense exhalations accompanied by strong tension in the diaphragm and abdominal muscles (typical of coughing). All these elements constantly accompany the poetic work, but most often appear between the lines, further disrupting its recognisability and at the same time giving a strong emotional character to the image of the main character.

Scene 6, or song. Nothing remains in the voice of the previous dynamic, diverse material, except for the lyrics – which are now completely understandable – and the melody to which they are matched. All accompanying elements have been transferred to electronic material, which in turn becomes very dense. It is as if all the inner physical effort and anxiety of the person, previously expressed by the performer, have finally detached themselves from her and transformed into something else.

The piece itself, which I call scene 6, should sound very naive, even somewhat restrained. The main element here is the melody, which consists mainly of seconds, fourths and fifths. There is no fixed key; as soon as there is a hint of a tonal centre, each subsequent phrase immediately takes us to a different functionality. Suspended harmonies in the electronic part further prevent tonal tensions from occurring in the piece. The rhythmic pattern of the piece is limited to very simple figures – mainly eighth notes and quarter notes, and the periodic change of metre (3/4 – 4/4) smooths out all accidental syncopations:

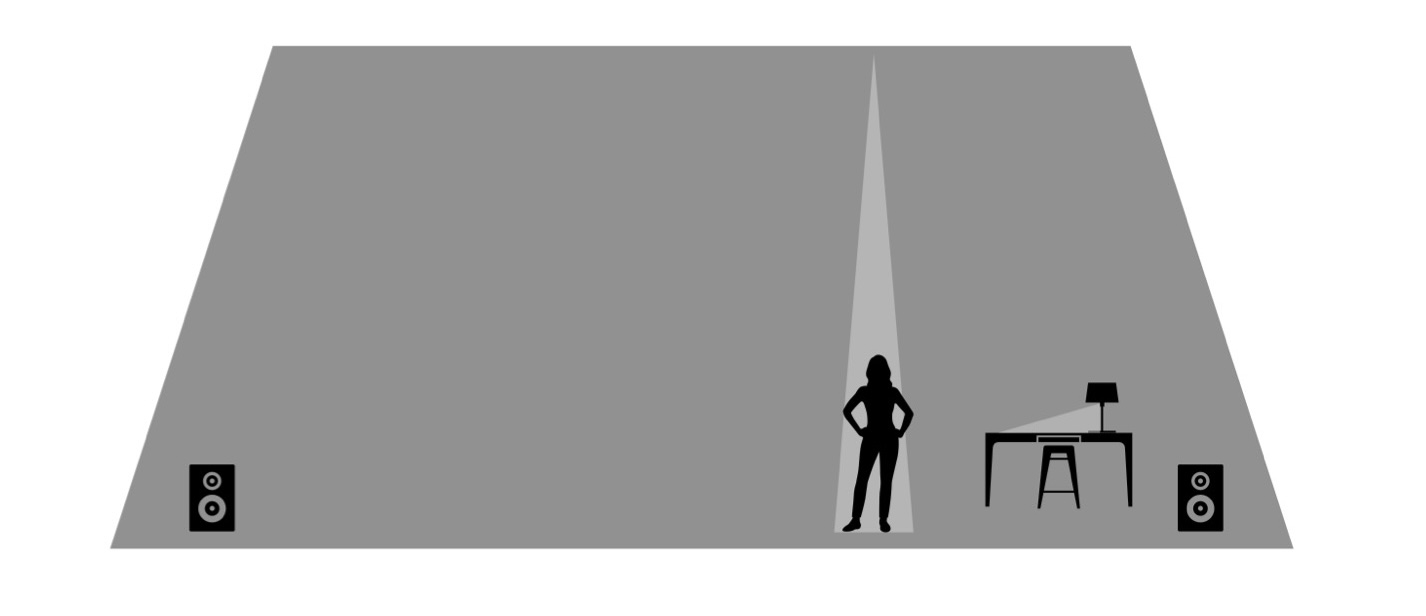

When I composed this melody, I did not model it on French or Ukrainian songs, but simply tried to follow the words. It is therefore worth adding here that this structure reflects only my own auditory perception of the French language. From a dramatic point of view, the interval between scenes 6 and 7 is probably the last moment of consciousness in which the character regains the ability to express herself. The work thus enters its final phase. It is worth noting that this is the first time I have used a small set design in my work. The stage is empty and dark, with the light falling only on the singer, a small black armchair and a desk with a lamp, a pencil and a piece of paper on it.

Scene 7 is semi-technical in nature, as I want to seat the singer at the desk. At the same time, I dramatically emphasise her ability to express thoughts that now become understandable and fully reveal the content of the poetry. In this case, the artist whispers and mutters two stanzas of the poem, one of which has already appeared in the piece, and the other is new, thus enhancing the intimacy of the moment. It contains a description of a star, the ruler of the night, whom the main character tries to find in every darkness.

Scene 8 is the coda: the singer no longer sings or speaks, but just sits at the table. Her voice resounds in the electronic part. At the beginning of my work with the singer, while recording the poem in the studio, I chose certain words from it that symbolise its essence for me: ‘rire á travers les pleurs’ [laughter through tears], ‘vivre’ [to live], ‘fleurs’ [flowers], etc. They all resound in this scene, but in the electronic part – and in the form of two different recordings, because I use two languages simultaneously and I wanted to keep them separate, not mix them, so that each could be understood individually.

In this way, I gave the Ukrainian language a quiet, distant sound, as if it were heard over the phone, by filtering out the low frequencies from the recording and amplifying the mid and high frequencies. The French speech, on the other hand, became a loud, detailed whisper coming from a very close distance, synchronised with the Ukrainian text. Parallel

to the bilingual poetry, the sounds of writing can also be heard: the performer is writing down the words she hears, which are amplified by a contact microphone attached to the surface of the desk. In this way, the thought, the text and its emotional content, with all its imagery and physical struggles, are ultimately separated from the character through the act of writing, which can, however, heal her.

The architecture of electronics

Electronics are often used in musical works as an additional instrument. It can accompany a soloist or be included as an equal part, thus entering into a dialogue with the other musicians and contributing to the ensemble sound. This is especially true when the electronics are not based entirely on a previous recording, but are performed live together with the soloist, and the dynamic nuances are adjusted on the fly. One of the key roles of electronics – which is difficult to ignore and, in any case, not worth ignoring – remains the creation of the spatial dramaturgy of the work, along with its overall sound atmosphere. The location and movement of sound in space are often fundamental characteristics, as is the position of the musician on the stage where the piece is performed. When real-time sound processing is used, electronics serve as an extension of the instrument or voice. Sometimes it takes the form of a meta-instrument that adds certain characteristics to the soloist’s musical gestures, other times it takes on the function of the soloist’s double, changing their part or obscuring it.

In …au ciel enflammée for soprano and electronics, I use many of these features, and the electronic part plays an important role in creating the sound atmosphere at the beginning of the piece. An important dramatic aspect is the one-minute prologue, before the singer even begins to breathe. The entire electronic architecture of the work is based on the use of onset detection, a mechanism that enables the live detection of amplitude jumps in the incoming audio signal (from zero to a specified value). In my case, each such instance serves as an impulse to trigger various processes in real time: from the activation of prepared samples by the voice, through the ‘freezing’ of individual sounds of the soloist, to the change of sound processing parameters. This is facilitated by interactivity, as well as the close connection between the soloist and the electronics.

In most scenes, the vocalist uses her voice to trigger the playback of short samples that are percussive in nature, similar to live singing. Sometimes these elements merge into a whole, creating a cloud of sound, and sometimes the vocalist ‘plays’ on the electronics (as in the case of multiple breaths in the piece). The samples include both abstract, synthetic sounds and pre-recorded and edited concrete sounds: screams, coughs, gasps, whispers, typing, etc. These clouds move along a programmed trajectory in space, but because they are activated by the singer’s voice, their location cannot be predicted in advance. This introduces an additional level of interactivity and theatricality, as the soloist hears the electronic sounds coming from a different place in the room each time and tries to react to them.

One of the most distinctive and obvious ways of processing voices in real time in …au ciel enflammé is the tremolo used in the piece (scene 6). It serves to gradually break down and undermine the very act of singing the text and ultimately separate the text from the person performing it. The emancipation of the poem, recited by the character on stage, consists in its detachment from space. The transformation into a meta-interlocutor is also achieved by electronics in the code of the piece, as is the aforementioned linguistic splitting.

Translation: Jan Topolski

The text is a selection of excerpts from the author’s master’s thesis entitled Die Stimme als Bestandteil des Körpers in der Schaffung vokaler Musik (am Beispiel des Stücks …au ciel enflammée für Sopran und Elektronik) written under the supervision of Professor Christian Utz at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Graz

Bibliography

John Cage, Silence: Lecture and Writings, Wesleyan University Press, Hanover 1961

Peter Manning, Electronic and Computer Music, Oxford University Press, New York 2004

Jennifer Walshe, The New Discipline, “MusikTexte” 2016 no. 149

More on Anna Arkushyna and her works see her official website. ↩

Translation: Vera Rich ↩

http://henri-abril.fr/lessia-ukrainka-poesie-ukraine. ↩