Avant-garde cocktail glass straws

Artistic resistance in times of war

In times of war, revolution, and other profound social upheavals, in which, traditionally assumed, ‘the muses are silent’, a specific art emerges, that actively intervenes in events. It is the result of powerful impulses of social and individual emotions, personal initiative and the need for participation. At the same time it results from the discomfort that traditional art is outmoded and insufficient1. Ukrainian society, which I left as a teen, has been in a state of instability since the birth of the Ukrainian nation-state in 1917-1920 and again since 1991. Born in the year of independence, I belong to the new generation of artists, living in Germany and travelling the world, who are striving for understanding and connection to cultural life in Ukraine, making the cultural gap between the so-called Western and Eastern Europe smaller.

Through music, I would like to learn something about the transformations in Ukrainian society and the cultural sphere in times of war. And since the massive migration due to the war, I am also interested in the spread of ‘Ukrainian’ culture beyond the borders of Ukraine, especially the spread of experimental electronic music and sound art, as well as the underground DIY music scene. I follow the summary of Ukrainian avant-garde history with fresh insights which I gained from interviews between 2020-2023 with artists and collectives who described their personal experiences of creating socially effective work in their field. Among them are artists from each of the following collectives:

1) Detali / Insha Osvita based in Ivano-Frankivsk,

2) The Institute of Sound /Women’s Sound based in Kyiv and across Ukraine,

3) Biorhythm based in Kyiv and on the Internet2.

This is a young group of experts who have gathered their personal experiences in the last seven to 20 years. While examining the lived realities of artists and activists, the central question of my ethnomusicological research was whether and how experimental music influences society (or parts of it) and vice versa – how does the current situation in the country influence artists in their creative work? The initial idea was to examine the after-effects of the Revolution of Dignity in 2013-14 and the war in the Eastern part of the country. Then the pandemics crashed in, followed by the full-scale invasion, both episodes having changed the circumstances drastically.

In psychology, there is a widespread assumption: everything unprocessed repeats therefore history must be understood and processed so that it can be considered ‘closed’. Only then can it move into the past and not stand in the way of the future.

In my conversations with artists, I asked myself what constitutes the identity of these people, what social issues affect them, what sounds they use, how they express pain or grief, what they distinguish themselves from in terms of arts and values, what they perceive in their social surroundings and want to change. To think about today’s artistic resistance without making a connection to the ‘avant-garde’ would be like starting a sentence in the middle. The term ‘avant-garde’ historically refers to the epoch between 1910 and 1930, driven by artistic pioneers with the urge to think the world anew. The artists of this movement strove to break through artistic, aesthetic, social, and ideological boundaries. Being self-reflective and critical, they saw themselves as an artistic-interdisciplinary and international movement. So, there lie the roots of globalised art as we know it today; for my generation of artists, it is as natural as finding the social impact or a certain degree of self-reflection that we try to convey in our art. After all, art and culture are also affected by profound changes and socio-political upheavals, and thus a fortiori by deep emotions, personal initiative and the urge to participate. ‘Experimental’ art also means forward-looking, seeking innovation, but this expression is clearly less connected to socio-political contexts than ‘avant-garde’, ‘social art’, artistic activism or ‘artivism’. A particular hotspot for such art is in Ukraine right now.

The mood of the Russian avant-garde in the years leading up to World War I, was not very different from the mood elsewhere – except that it started a little later and sounded and sounded a bit shriller. It was part of the fin-de-siècle feeling, the decadence and symbolism, of protest against a life that was too quiet and orderly. It was the same feeling of suffocation that the generation of 1914 complained about all over Europe, the same boredom and search for a new faith.3

The history of the Soviet, and especially the Ukrainian, avant-garde was marked by several socio-political events. Among the most important events was World War I; the February and October Revolutions in Russia in 1917, and the formation of the first nation-state of Ukraine in 1917, which did not survive beyond four years; the founding of the Soviet Union in 1922; the Holodomor instigated by Stalin; and World War II4. During the numerous regime changes from the Habsburg monarchy to brief Ukrainian nation-statehood to the Soviet regime and the German occupation of 1939-45, the society experienced a state of permanent unrest. The whole period was accompanied by unstable politics as well as inconsistent territorial reforms that were Romanianised, Polonised or Russified5.

The avant-garde was affected by these fast-moving transformations as well as sociopolitical upheavals. In the Soviet Union, the avant-garde was quite welcome as long as it adopted the rules of the Soviet government. The reflexive voices of avant-garde artists on these aggravated social conditions are indispensable for understanding the times and circumstances. In many ways, parallels can be found with contemporary Ukraine, ‘where the avant-garde plays a significant role in the debates surrounding cultural memory6.The history of the Ukrainian avant-garde 100 years ago would be much easier to follow if it was only about ethnic Ukrainian artists. However, this raises the question of whether artists at that time identified themselves as ‘the Ukrainian avant-garde’ at all. Therefore, in the following, I will rather refer to the cultural territory of Ukraine when I write about the ‘Ukrainian avant-garde’. I do not mean exclusively the Ukrainian ethnicity or nationality.

While the mass culture of Ukraine, which had been Sovietised since the 1920s, was marked by several campaigns of Russification, the opposing or system-critical positioning of some avant-garde artists from the 1930s onwards was labelled as ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism’ and banished, remaining underground or in the personal archives of their creators and friends7. Thus, many works and ideas remained unpublished until 1990, often due to state censorship or self-censorship on the part of the artists. Only with the opening of Ukrainian archives in 1990, did it become possible to access and process them. Nowadays there is literature by Slavic scholars, among them Myroslav Shkandriy, Vera Faber, the art historian Myroslava Mudrak, and Stefan Simonek, who reviewed the history of the innovative art of the last century in Ukraine separately from Russian art history.

The third great art of our time, which arose in connection with the advent of radio technology, is music. By affecting millions of people, it is intended to tear them out of the tonal limitations of tonality. A great storm of tempo sounds is a yet undiscovered land in front of the ears of musicians and listeners. Composers, open it up! Fill the ether and the air with sounds no less varied and beautiful than the sounds of a disorganized musical life. Make the rhythms more complicated and write them down, beat on new instruments and leave the boundaries of jazz and termenvox!8

In Ukraine, the avant-garde is divided into two periods: The ‘first wave’ began around 1920 and ran until the beginning of the 1930s9. Its musical development was stopped by the spread of the Socialist Realism movement in the USSR and he accompanying struggle against bourgeois formalism, which included exhibitions, ballet, opera, and the music of the avant-garde10. The propagation of a Soviet musical aesthetic began in 1918 when the Bolsheviks established the People’s Commissariat for Education (short: Narcompros) for ‘cultural enlightenment, education and promotion of artists of the Soviet Union’11. The sub-department for music was called MUZO. From then onwards, and until the end of the USSR, Narcompros was responsible for approving musical tours, concert programs, announcements, and the distribution of concert tickets.

The Glavrepercom (Main Repertoire Committee) decided which works could be performed. To show the proletariat the roots of their culture was accompanied by the necessity to clearly de-ne what Soviet proletarian culture was in the first place12. While the ‘Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians’ (Russian: Vserossiyskaya Associaciya Proletarskich Muzykantov, or RAMP for short) implemented the party directives from 1923 onward, the Russian avant-garde formed a more liberal and progressive counterpart in the Association for Contemporary Music (ASM). The ASM did consider the Western avant-garde, but only to distinguish itself from the Western avant-garde and to develop its own compositional systems 13. It was a matter of the continuation and revolutionisation

of the occidental tonal system, as in the ultrachromatic condensations of the tonal space in Nikolay Obukhov, the quarter-tone music of Ivan Vishnegradsky or Nikolay Roslavets’ dodecaphonic ‘synthetic sounds’. […] With the dissolution of the traditional tonal system, the dawn of a new high culture freed from the shackles of tradition.14

The greatest challenge since the mid-1920s for the musicalavant-garde in Russia was how to combine their revolutionary thinking with the given Soviet musical aesthetics. It was unclear how the guidelines set by the state could be integrated into their own creation of compositional material. If this was true for the avant-garde in the centre of the empire, it was also true for the composers on the periphery, perhaps in a somewhat weaker form, and here I consider Ukraine as part of the Soviet periphery. However, a closer look at the artistic milieus of Lviv, Kharkiv, and Kyiv reveal differently influenced musical creations.

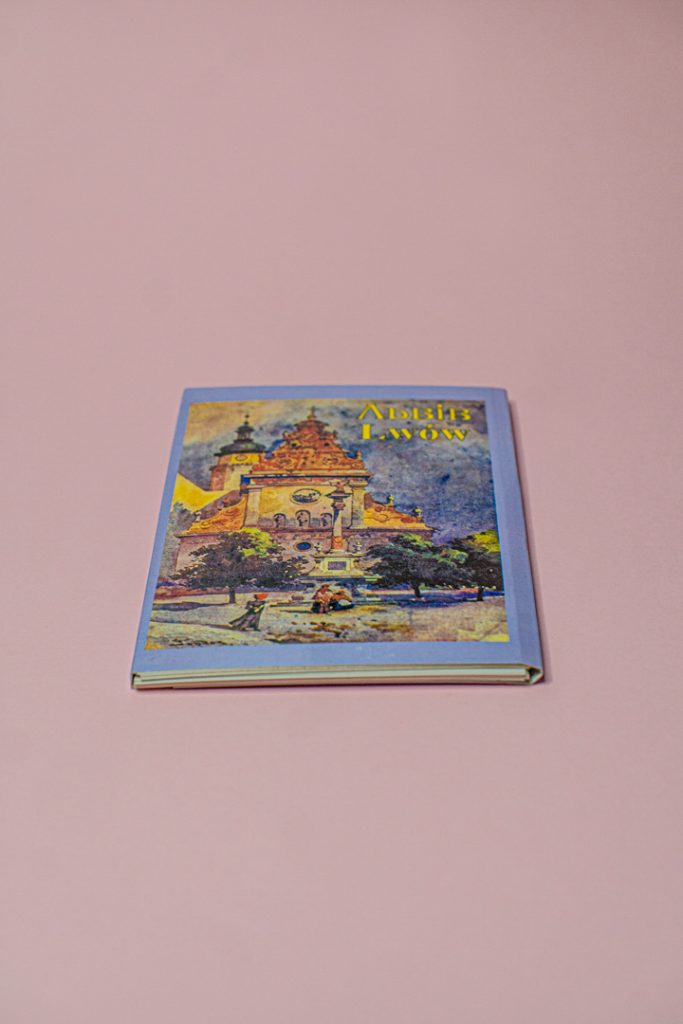

The western regions with the urban centres of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, Chernivtsi, and Rivne belonged to Poland, Romania or Czechoslovakia until 1939. The Ukrainian avant-garde of the interwar period in the West had more developmental difficulties than the rest of Ukraine which belonged to the Soviet Union. The city of Lviv was not an avant-garde metropolis, and the focus was on Ukrainian folklore art here. The city was also under Polish rule. Neoclassical and dodecaphonic compositions by Lviv-based Polish composers with Jewish roots – Józef Koffler (1896-1944) and Tadeusz Majerski (1888-1963) – reflect the interwar period15. Majerski survived the war but submitted himself to strong external censorship by turning away from dodecaphony as a compositional technique16. The dodecaphony, according to the music journalist Lyobov Morozova, ‘became the symbol of the new system and the language for honest narratives about the horror of war’17. The formation of the Artes [ukr.: Áртес] group which both composers joined, was once again multiethnic and consisted of Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish members, among them Otto Hahn, Marek Włodarski (Henryk Streng), Jerzy Janisz, Ludwik Lille, Aleksander Krzywobłocki, Roman Selsky, Margit Reich-Selska, Tadeusz Wojciechowski, Pavlo Kovzhun, Andrzej Pronaszko, Debora Vogel, and other artists18. Due to endless murders, deportations, and numerous stories of emigration of the musicians of today’s Western Ukraine, there is a difficulty in retracing the musical history of Lviv between the wars – a city in which art is interwoven with ‘the peasant idyll, sometimes by the petty peasant leitmotifs of suffering, […] isolated and isolating itself from the global context’19. In Poland, the artists of the Artes group did not gain recognition, as their play with the primitive and the provincial was considered to be part of the Ukrainian nationalist movement20. Today, though, Artes is also referred to as a Polish group of artists, with crucial differences in storytelling21. Researchers from both Poland and Ukraine, often in cooperative academic projects, are now processing the history of the avant-garde in Lviv and Western Ukraine22.

To whom did the avant-garde belong? Of course, the avant-garde belongs first and foremost to itself, but according to cultural historian and director of the Ukrainian Institute for Cultural Diplomacy Tetyana Filevska, viewing art history within the framework of the nation-state of Ukraine is an important lens necessary ‘to reappropriate the non-obvious cultural heritage with the lost particles of the Ukrainian cultural field.’23 In the first third of the last century, the Ukrainian avant-garde was to be seen more in the context of the Russian Empire and other countries that Ukrainians emigrated to such as Canada, the USA and Western Europe, rather than only within the national borders. Today, again, Ukrainian culture clearly extends beyond the borders of the nation-state. Also, while Ukraine is now (forced to be) in the middle of a national liberation movement, the real question is about how to actually avoid nationalistic tendencies in a globalised world.

In Kharkiv, among the important artistic formations was the ‘Association of Panfuturists’ [Асоціація панфутуристів or Аспанфут] founded by the artist and literary figure Mykhaylo Semenko. In 1924 the group changed its position to Socialist Realism and was renamed as the Association of Communist Culture. Here again, we can see the influence of the USSR’s cultural policy on the art and culture of the country. Kharkiv was the capital of Soviet Ukraine from 1918 to 1934 – a status that had administrative and formal character. Although Russian was the predominant language spoken in Kharkiv, the city was more oriented toward European and cosmopolitan culture. An important name that emerged from the Kharkiv school, according to musicologist Iryna Dratsch, is that of the composer and pedagogue Semen Bohatyryov24. He was interested in the New Viennese School, the dodecaphony of Schoenberg, and serial composition and passed these interests on to the graduates of his composition class.

Some interesting experiments in ‘sound poetry’ [збукопоезiя] at the intersection of music and language were done in Russian, Ukrainian, Yiddish, and at the time popular arti-cial language Esperanto. According to the Socialist Realist understanding of art, even the publications about jazz and foxtrot as well as published sheet music to the jazz etude by Yuliy Meitus (1903-1997), were seen as hooliganism! Meitus was a member of the Association of Revolutionary Composers of Ukraine [Асоціяція революційних композиторів України, in short: ARKU]. In ARKU’s short period of existence from 1927 until its dissolution in 1932, other young composers besides Meitus and Koljada worked to develop Ukrainian symphonic music, opera, and instrumental chamber music25. Meitus was considered to be a musical ‘opponent’ because he used to work with elements which were common in Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar folk music26. Some pieces were based on texts by Ukrainian poets Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Franko. The modern processing of folklore also took place in other artistic branches of the so-called folk futurism movement.

This tension in the avant-garde art movement in Ukraine caused an ideological split from the mid 1920s onwards. Some groups stood for artistic independence from Soviet funds and authorities and thus were against the imposition of ideas. Others worked in close cooperation with the Soviet state and gained recognition and reach, among them the composer Boris Tihonov (1901-1988), in his early years, Halyna Tyumeneva (1908-1999) and Lev Revutskyi (1889-197). Those artists who addressed taboo subjects were at least admonished, if not threatened or punished, which you can see in examples below. The avant-garde criticism of musical-aesthetic norms and formalities such as classical harmony and tonality did not suit the government. The so-called ‘oppositional’ avant-gardists like Meitus and Bohatyryov wanted to break with old traditions and artistic aesthetics and invent new rules of composition and performance. They wanted to be outside of a tradition with their experiments, while in Russia a new music for the proletariat was being designed.

In Kyiv, power changed several times between 1917 and 1921. After the establishment of the first Ukrainian Central Council in 1917, democratic principles were implemented for the first time in Ukrainian history. More specifically, it was about ‘the national-personal autonomy’, a right to protect national minorities such as Russians, Poles, Jews, etc. It was passed on January 9, 1918, on the initiative of the Jewish Ministry. The law was intended to ‘protect the right of all non-Ukrainian nationalities to independently organise their national life.’27. On this basis, Jewish culture in Kyiv, despite the Civil War and mass pogroms, had access to better opportunities than in other parts of Eastern Europe28. Subsequently, in January 1918, a League of Jewish Culture was founded, today known worldwide as the Cultural League. Literature, fine arts, librarianship, school education, adult education, publishing, music, and theatre were all included within its remit.

The workers’ movement under Lenin promoted the idea of freedom for all and condemned the anti-semitism of the Russian tsarism29. It was about the return to folk art in the Soviet Union on the one hand. On the other hand, it was about the assimilation of the peoples and their turning to solely valid Socialist Realism, which was propagated until the 1980s. Both Ukrainians and Jews suffered from linguistic prohibition and Soviet censorship as soon as their works suggested a trace of ethnic or national identity, and from the 1930s onward, mass imprisonment of Jewish and Ukrainian intellectuals and artists occurred under the rule of Stalin30.

On September 29 and 30, 1941, one of the worst massacres of World War II took place in the city of Kyiv. On these two days, 33,771 Jews from the city of Kyiv were taken to the Babi Yar ravine and killed31. However, it was not until February 1944 that Nikita Khrushchev received an official report on the atrocities at Babi Yar. Admitting that the Nazis primarily murdered Jews as a group meant that the Soviet government would have to acknowledge the existence of Jews as a minority in Soviet society. The author Ruth Schweitzer describes the case of the Jewish-Ukrainian composer Dmitri Klebanov, who composed the symphony for the ‘Remembrance of the Martyrs of Babi Yar’ to commemorate this event. Tough there were rehearsals for this symphony in Moscow in 1949, the performance was ultimately cancelled because ‘it seemed unpatriotic to focus on Jewish victims rather than Soviet mundanities.’32 According to Schweitzer, this was only one example of the campaign against ‘rootless cosmopolitans’, especially Jewish artists of all stripes, who were arrested or killed. Anti-semitism was absurdly intensi-ed after World War II in Ukraine and the Soviet Union, Schweitzer writes.

While in Kharkiv the musical avant-garde had become increasingly conformist, a strong avant-garde scene developed in Kyiv after the end of World War II. The scene expanded in the 1960s, hence its colloquial name – the Shisdesyatnyki (Sixties). By then, the music and its creators had already gone through 30 years of Soviet cultural policy. The government had its eye on the head of the composition class, Borys Lyatoshynky, at the Kyiv Conservatory, who did not teach and compose ‘according to the rules of socialist realism.’33 He was a board member of the Association for Contemporary Music [Асоціяція сучасної музики = Asotsiiatsiia suchasnoi muzyky, 1924-32], which had attracted early attention, especially with its formalistic and cosmopolitan tendencies, for which he was indicted in the late 1940s. Stalin’s commissioner for culture, Andrei Zhdanov, punished Lyatoshynsky by rejecting several of his works with a ban on performance in 1949, because in his opinion Lyatoshynsky had opposed Soviet cultural reforms.

After that, Lyatoschynsky focused on his work at the conservatory. The fact that he stood up for his right to have his own style and his own artistic position attracted many other like-minded people to him, including his colleague Igor Blazhkov who had some contacts as a conductor from across the Iron Curtain. Musical (post)-avant-garde inspiration came from there – aleatoric, sonoristic, musique concrète, and from the 1970s onwards, electronic music and algorithmic composition. Scores and radio recordings were secretly passed backwards and forwards, despite the strict measures that were taken against the rebellious composers of the Sixties.34.According to Yelena Zinkevych, these included: expulsions from the conservatory and cancellations of scholarships, exclusion from the Union of the Composers of the USSR, bans on publication of works and performances, and bans on leaving the country for several years.35.

What made the Kyiv 1960s avant-gardists musically distinct? The composers counted among them were classically trained and knew the folklore traditions. Each of them had their own style, but their distinctive features of musical expression include dissonant 12-note tone rows, atonal improvisations, gestural impulsiveness, unusual sound generators (with hidden symbolism, e.g. matches in Silvestrov’s Drama), slow harmonic resolutions to dissonance (‘discorded melophony’) and Ukrainian folk songs manipulated beyond recognition. The strict repertoire requirements were ful-lled, but in order to cover up the material and references to Ukrainian folklore, for example, they worked with means of defragmentation and collage (‘polyphony of styles’), overlaps (of harmonies, melodies, rhythms), with unexpected jumps in registers, musical turns, and, in contrast, with contemplative moods. Many works can be read as a processing of individual and collective pain. After the war, psychological wounds remained, which were concealed by the Soviet government. Thus, the musical avant-gardists of Kyiv were once again in opposition, finding ways to express all of this in their music.

Wrap-up

Musically, in my opinion, the Ukrainian avant-garde played with variations of what was happening in the Western European avant-garde. Its contribution to the avant-garde depended on which region of Ukraine it came from: in the Western Ukrainian city of Lviv, it was a play on what was considered ‘primitive’ and ‘provincial’ according to the dominant Polish culture. This was especially true in regards to the depictions of folklore. Because of its previous affiliation with Poland, the city of Lviv and its art tended to be associated with Western European institutions. The example of the Kharkiv Music School and the musicians belonging to the Avanhard group highlights the futurism and constructivism movements that flourished in the city. In these revolutionary innovations of the musical language, the ethnic-national aspect was also present in Kharkiv, but the predominantly Russian-speaking capital of Ukraine was closer to the Soviet centre of Moscow. Despite the intensive exchange between these cities, the Kharkiv Music School could not escape the pressure and control of Moscow and could not live up to its own avant-garde standards after World War II.

The artistic activity then gravitated towards the new capital Kyiv. The second wave of the musical avant-garde after the war was inevitably adapted to the system, but subliminally included the motifs of oppressed ethnic groups as well as criticism of Soviet rule. It was also concerned with the performativity of pain, loss, and mourning, of repressed war traumas, and of the need for reparation, recognition, and recon-guration of the past. In the transition to the 1970s, increasingly electronically generated sounds attracted attention and the musical avant-garde was characterised by a polyphony of styles, or ‘polystylism’ à la Schnittke36.

There has been no mention of electronic or electroacoustic music so far. The Kharkiv musicologist and vocalist Alla Zahaykevych o,ers a review of the history and details about the electronic innovations that domestic and diasporic Ukrainians have been involved in since 1910. As an example, she mentions the electronic Ukrainian artists Maximilian Brand and Yevhen Scholpa37. According to Zahaykevych, the reappraisal of history often results from detours and contacts abroad. Compared to other regions of the world, electronic experimentation in Soviet-Ukraine, apart from popular music, was a rarity until the 1990s. In its oppositional spirit, the musical avant-garde in Ukraine was strong, almost martyr-like, for it was often a matter of life or death in the captivity of imposed ideologies. It spoke of marginalised national cultures, which were expressed in their local languages, but at the same time were striving for a modernist utopia. Myroslav Shkandriy said the following: ‘Utopianism and faith in the future were a part of this modernism, but the local was the vehicle for reaching this future. A key to understanding the semiotics of this art lies in the cultural discourse out of which it grew.’38

The artistic ‘in-between-ness’, peripherality and cosmopolitanism

In the previous (inter-peripheral) Ukrainian centres of the avant-garde, such as Kharkiv, Kyiv, Odessa and Lviv, reports and sources of biographical research testify to a rather heterogeneous community in which multilingualism was common39. It was almost normal to pursue artistic activities in several cities, as people went abroad to study art or composition. In general, the metropolises preferred by artists of the time were St. Petersburg and Moscow, as well as Paris, Munich, and Berlin. For music composition, in particular, the cities of Vienna, Budapest, and Leipzig were popular places of study for Ukrainian musicians. Te artistic interest in Ukraine in the decade between 1910-1920 tended to be directed more towards the ‘East’, i.e. in Russia, where there was already a fairly strong higher education system (as well as a strong basis of common prehistory and linguistic understanding). Therefore many studied and later worked there. In the ‘West’, especially in Germany, Italy, and France, the boom of the avant-garde had already happened and was advanced in discourse. The avant-gardist ‘dual citizens’ from Ukraine, who were active in the West, brought Ukraine into the Central European consciousness in the first place – despite a rather lacking identification with their region and country since they themselves were not necessarily ethnic Ukrainians. In the visual arts, there were some names, such as the well-known painters Kazimir Malevich and David Burliuk, who identified themselves as Ukrainians, and others such as Sonia Delaunay, Alexandra Exter, Vladimir Tatlin, and Alexander Archipenko, who ‘associated their work with a Ukrainian inspiration.’40 The cities mentioned above in Russia and in Western Europe were the centres of the avant-garde at the time, so the Ukrainian cities, with their avant-garde scenes, were rather peripheral stations in the art world.

While the Soviet Union was supported by many artists because of its internationality, Russia as a political centre of power which dictated artistic norms was criticised and rejected. This is clear from the research published by Vera Faber in the journals Nova Generacija and Avanhard, in which numerous critical artistic works, manifestos, and polemics of the avant-garde can be found41. The twofold peripheral position between the ‘primary center’ of Russia, from which Ukraine turned away in the 1920s, and the ‘secondary center’ of Western Europe meant that Ukrainian artists were in exchange and orientation in both directions. Among other things, the All-Ukrainian Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries made efforts to bring East and West together [Українське товариство дружби і культурного зв ́язку із зарубіжними країнами] that was active from 1928-31 and from 1940-8542.

The ‘in-between peripherality’ in which Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek locates Ukraine, should be critically considered within postcolonial studies, not least because Ukrainian artists have experienced terms such as ‘imperialism’ and ‘semi-colony’43. In their polemics, they understood ‘he sense of ideological, political, and cultural oppression’, although the term “semi-colonialism” had already been used at the time of the founding of the Soviet Union in order to distinguish itself from Russian Tsarism44. According to Edward Said, ‘imperialism […] is the practice, theory, and the behavioural styles of a dominant metropolitan centre dominating a remote territory’ 45, provided that the rule is accepted by the ruled. This was not necessarily the case in Ukraine. According to Tötösy de Zepetnek, the system of the Soviet Union produced a peculiarity of colonialism, ‘that manifests itself in a ‘secondary’ colonisation through ideological, political, social, cultural, and other means.’46. A dynamic confrontation with discourses in the Russian centre led to a reevaluation of norms and traditions on its Soviet peripheries. The past, and the current turn, toward Western Europe is less critically scrutinised. This is possibly due to the idea that Western Europe saw Ukraine as a rather unknown, formerly Sovietised country, in contrast to Russia, which spread dominant narratives of Soviet art history worldwide.

It is noticeable that the perspective of Ukraine as a cultural space is missing from the international avant-garde discourse. On the one hand, this was adapted into the dominant discourse of Russia or the Soviet Union, and on the other hand, it is because the (literary) language of Ukraine lacked official status. The ‘Ukrainian avant-garde’, which is important for Ukraine’s cultural identity today, was read in the past as ‘the Russian avant-garde’. Russia invested money and energy into writing and archiving history, while the 30-year-old independent country of Ukraine has only been seriously devoting resources to writing an alternative narrative for about 10 years. This is also accompanied by a collective processing of historical events and a growing cultural awareness. Presumably, it was not the lack of productivity of the Ukrainian music avant-gardists, but rather the lack of visibility.

Contemporary art in Ukraine is also characterised by an examination of the first generation of the Ukrainian avant-garde and its themes. There is thus a historical understanding of common experiences of occupation, foreign domination, and lack of freedom.

The revival of the lost

With the collapse of the Soviet infrastructure, all cultural-industrial frameworks were lost and the new Ukrainian state completely neglected its own cultural life. With independence in 1991, a neoliberal policy emerged, followed by a reorientation towards the West, new travel opportunities, and new role models, which served as ‘copy models’ during this identity crisis. This can also be seen in the quality of music during the 90s and 00s. The Revolution of Dignity in 2013-14, in which art played a major role, was a turning point in history and a meeting point for people of different political attitudes and social backgrounds. This is where an older generation who grew up in a centralised world met a younger generation brought up in a globalised world that is no longer isolated. Since then, contemporary art and music in Ukraine have been on the upswing again.

The state’s recognition of certain artistic biographies depends on how strongly the theme and idea of an artistic work compliments the idea of the state. Cultures and nations look for artistic representatives. According to the Soviet understanding, artists should be presentable and acceptable. If not, there were problems and artists lost their right to criticise society. The pressure to conform created a mentality that could not be easily overcome after 1991. It is slowly being overwritten.

Artistic and musical works are still closely associated with the biographies of their creators. However, it seems that the poles have reversed. If artists in the Soviet Union had to prove their closeness to the Union by dedicating a pro forma poem to Lenin, artists in today’s Ukraine are tested for being ‘pro-Ukrainian’. The politics after 1991, and especially after the Revolution of Dignity in 2013-2014, is characterised by decommunisation and Ukrainian rootedness – korenizatsiya. The maintenance of the Ukrainian language and the sovereignty of the state are considered the highest priority.

I am most interested in the broader question of how artists deal with the past and the future. Is it possible to separate from the ‘semi-colonial’ past without excluding everything that is not ‘yours’ and without falling into ‘colonisation-compensating thinking’? The danger behind it is ‘defamiliarisation’, which is the sense of groundlessness and depression that may follow the impulse to reject everything that one has learned or that one has been taught. The cultural scientist Madina Tlostanova points out that it is important, after a ‘delinking process’ from, for example, a theory, to look for new theories, which she calls ‘relinking’47. Interestingly, artistic work also consists to a large extent of delinking and relinking processes. This includes abstracting and collaging, the reweaving of the world, in which it is brought into the absurd or otherwise transformed, from the imagination of a future that is not based on the nostalgic past. The connection to folkloric or indigenous roots, alongside experiences of globalisation, mechanisation, and digitalisation give many post-colonial artists the possibility to free themselves from colonial history. Soviet nostalgia no longer seems to be an option for contemporary artists, either because they did not experience it or because they no longer identify with it. However, there is still more investigation to be done in this area.

Current Ukraine and decolonization struggle

For Ukraine, as well as for the entire post-Soviet space, dealing with the issue of decolonisation is indispensable. It is a matter of becoming aware of oneself and one’s own past in order to finally let go of it and look for a new position in the world. The importance of these themes is confirmed by the director of the research platform of the Pinchuk Art Center in Kyiv:

We are a young country, and that is why the question of self-identification plays a huge role in contemporary artistic works: who are we, what is our national identity, what myths do exist about this identity, who are we on the world map? Our past and its reflection takes a lot of space. […] Neither are there limitations, nor the function of boasting something, because the state institute of commissioning arts, as it was in Soviet times, no longer exist. Art has ceased to be a part of propaganda and an instrument of popularisation. The individual is now important: the opinion and reflections of the artist. There is no longer someone who dictates the structure of everyday life saying: Paint Danaë, but in such a way that she looks like my wife!48

The expression ‘being in between’ describes the state of indecisiveness or being torn back and forth. In fact, Ukraine’s situation is not clear-cut. It has influences from both the East and the West and carries these elements within itself, which makes it richer. The phenomenon of the Iron Curtain during the Cold War drew a systemic, and therefore ideological, border between the Soviet Union and the USA/Western Europe – between capitalism and socialism. Today, like any country open to the media, the country carries a number of global influences. What happens to art and culture in the course of such ideological shifts? How does Ukrainian society deal with changing cultural influences? To what extent is it responsible for this?

What is on the minds of artists in Ukraine? Half a year before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Irina Tofan, in collaboration with Pinchuk Art Centre, examined the top five themes or trends in Ukrainian art over the past five years49. She described not only the tendency for museums to want to be more modern and accessible to society, and the increasing number of alternatives to traditional artistic education, but also noted that the themes of ecology and the re-opening of archives have become particularly interesting for Ukrainian artists. At the same time, she questioned whether these issues are now also the responsibility of artists: a justified question that comes to a radical head in times of war! As was the case before Russia’s war, artists often take on those tasks when the state does not have the resources or ability to do so. Synonymous with artistic activism, electronic musician Olesia Onykiienko (a.k.a. NRNF) speaks of ‘cultural humanitarian aid’, even though the artists have not trained as social workers, ecologists or archivists, and none of them have ever imagined that they might have to hold a gun instead of a violin bow. During the war, many of them have been engaged in humanitarian aid (e.g. care of the elderly, soldiers, children, and internally displaced persons) or in the protection and safeguarding of cultural heritage, e.g. archaeological museum collections, collections of national celebrities as well as young contemporary art and culture and their digitisation or evacuation from unsafe to safe regions.

If they still have time and energy left in the wake of all the everyday problems (e.g. power cuts, rising food prices), they act as cultural diplomats; in addition to the country’s military self-defence, cultural workers see themselves as soft power. Unlike in Russia, Ukrainian artists do not seem to question expressing their own position on a national and international stage. It is inconceivable for them to remain silent, calling out against oppression.

On the axis between folk arts and alternative culture(s), there is a negotiation of artistic diversity and its forms, and thus of the legitimacy of the country’s peoples and ‘small’ or subcultures. Since the Revolution of Dignity in 2013-14, which triggered linguistic reforms and the impulsive cleansing of public spaces of any sign of the Soviet era, Ukrainian art history is being discussed anew. The extent of the Soviet Union’s appropriation of art and artists’ biographies has been publicly reappraised afer Ukrainian independence in 1991; a search for the lost, the repressed, the forbidden, the overlooked. At the same time, this search also raises the question of whether such a large window of time as the Soviet one can be left out of Ukrainian historiography at all. Despite the wounds and collective traumas accumulated in society during the World Wars I & II, the Holodomor, the Chernobyl disaster and other ‘minor’ crimes of the Soviet era, the aim is to find an adequate way of dealing with history.

Putin’s encroaching imperial war policy has been trampling on the wound since the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Since February 24, 2022, cultural emancipation, which may have a different meaning in a future globalised society, has been on a clear course to free itself from the Russian sphere of dominance. It is impossible to say what will happen to the rather young, fragile structures that emerged in terms of cultural politics after the Revolution of Dignity. They continue to stand in a European, Eurasian, global context whose future is hardly predictable.

The Covid-19 pandemic in 2020-2022 was a good example of unexpected events that can have a great impact on art and culture worldwide. On the one hand, it slowed down cultural life, on the other hand, it brought a unifying experience worldwide for all artists and cultural workers. And what will happen to the already ‘precarious art’ in Ukraine if the consequences of the pandemic are multiplied by a war? Does the feeling of competition between cultural workers prevail over the desire for community and interpersonal connections? A globalised world requires globalised thinking. Therefore, the examination of mixed identities, voices of artistic minorities, diasporic movements, subcultures and their environment can contribute signi-cantly to the understanding of today and today’s arts.

The reason that artists have difficulties in detaching themselves from the entanglements with politics and why they (have to) repeatedly offer artistic resistance becomes very clear: they are trapped in the specific context of their place and time. They become active in their own liberation in order to create a framework for action or to build a utopian counterpart. Many young people find themselves in the inclusive, ecological, diversity- and gender-conscious utopias of alternative, experimental music and art. And the good thing is that today’s artists and their initiatives have the potential to soon become new cultural institutions that future generations of artists can rely on.

Anatoli Strigalev, Agitprop – die Kunst extremer politischer Situationen, in: Berlin-Moskau/Moskau-Berlin 1900-1950, eds. Irina Antonowa, Jörn Merkert Natalja Adaskina, Helen Adkins, Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1995, p. 111. ↩

Case study I: Detali, site founded on 07.05.2017; Insha Osvita, site founded 18.01.2015; Case study II: Institute of Sound [Інститут Звуку], site founded 09.02.2019 and Womens Sound, site founded 10.02.2019; Case study III: biorhythm, site founded 01.02.2020. ↩

Walter Laqueur, Der Zusammenbruch der alten Welt in: Berlin-Moscow/Moscow-Berlin 1900-1950, 2nd edition, Irina Antonowa, Jörn Merkert, Natalja Adaskina, Helen Adkins, Prestel-Verlag, Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1995, p. 90. ↩

„Holodomor” means famine. This greatly affected the population of Ukraine in 1932-33. The „academic” food ration introduced by Gorky during the war saved many artists from starvation. Lyubov Kyanovska and Helmut Loos, Ukrainische Musik, Idee und Geschichte einer musikalischen Nationalbewegung in ihrem europäischen Kontext, Gudrun Schröder Verlag,Leipzig 2013, p. 15. ↩

The western region of Galicia and the northwestern region of Volyn were Polonised. The southwestern Bukovina and Bessarabia were Romanianised between World Wars I and II. ↩

Myroslav Shkandriy, Avant-Garde Art in Ukraine, 1910-1930. Contested Memory, Academic Studies Press, Boston 2019, p. 13. ↩

Ibid, p. 12. ↩

Valeriyan Polishchuk (1897-1938), 1st issue of Bulletin Avanhard, Kharkiv, October 1927, Kharkiv, transl. author. ↩

Hanna Skrypnyk, term Avantgardism, in Ukrainian Music Encyclopedia, Publishing House of the Institute of Art Sciences, Folkloristics and Ethnology NAN, Kyiv 2016), pp. 20-21. ↩

Svetlana Svereva, Aleksandr Kastalskyi, Idei, tvorchestvo, sud ́ba, Vuzovskaia Kniga, Moscow 1999, p. 182. ↩

Michael John, Ideologie und Musik – Über die Anfänge einer sowjetischen Musikästhetik in den 20er Jahren, in Die Anfänge des sozialistischen Realismus in der sowjetischen Musik der 20er und 30er Jahre, projekt verlag, Bochum/Freiburg 2009), pp. 278-300. ↩

Ibid., p. 281. ↩

Ibid., p. 284. ↩

Ibid., p. 285, transl. author. ↩

Lyubov Morozova, Galician Dodecafony: Josef Koffler and Tadeusz Majerski [ukr.: Галицька додекафонія: Юзеф Кофлер і Тадеуш Маєрський], „Lewy Bereg”, 02.02.2019 and Maciej Gołąb, Józef Koffler, Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, Kraków 1995. ↩

Lyubov Morozova, Ibid. Tadeusz Majerski’s Three Works (1935) were already composed in the classical major-minor system with a very subtle use of the 12-tone technique, so that they were even included in the collection of the Piano Compositions of Ukrainian Soviet Composers. ↩

Lyubov Morozova, Ibid. ↩

See entry Artes Group of Artists [and other stories of Lviv Modernism], Center for Urban History, Lviv 28.05.2021. ↩

Cf. Andriy Boyarov, Sofia Dyak, Iryna Matsevko, Culture (Without) Spaces: On Avant-Garde Heritages in Lviv, Center for Urban History, Lviv. ↩

Cf. Karolina Koczynska, The Myths of Surrealism in Poland: the story of ‘artes’, 1929-1935 (p. 1), University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh College of Art, presented in 2017 at the IV International Doctoral Forum on Eastern European Art History at Humboldt University, Berlin. ↩

You can compare information about the Artes formation with this blog entry: Artes: photography & visual arts, culture.pl. ↩

Some examples of such multi-national academic projects were initiated by Modern Art Research Institute, Prisma Ukraïna – Research Network Eastern Europe by the Forum Transregionale Studien or by the institute of Ukrainian studies at Viadrina University in Frankfurt (Oder). ↩

With this provocative question, Pinchuk Art Centre in Kyiv opened an online discussion series on 11.03.2021. Кому належить авангард? (Who owns the avant-garde?). In the first episode the artist Nikita Kadan, art historians Oleh Ilnyzkyi and Tetyana Filevska discuss with curator and moderator Lesia Kulchynska. ↩

Cf. Iryna Dratch, Charkowska kompozitorska szkola, „Zelena Lampa”. ↩

These include Mykhailo Verykivsky, Pylyp Kozytsky and Valentyn Kostenko. Cf. entry on Association of Revolutionary Composers of Ukraine [Ukr.: Асоціяція революційних композиторівУкраїни] , in: Encyclopedia of Ukraine, 2011, status: 11.08.2021. ↩

Folkloric elements were found in Meitus’ orchestral suites, choral-orchestral works and in 14 operas, of which Perekop from 1938 is the best known opera. ↩

Aspects of Jewish Musical Culture in Ukraine. The Music Section of the “Cultural League” in Kiev, in: Ukrainian Music. Idea and History of a Musical National Movement, Gudrun Schröder Verlag, Leipzig 2003, p. 11. ↩

According to Simon Dubnow, between December 1918 and April 1921 there were over 1200 pogroms in which at least 60,000 Jews were murdered. Both the White and Red governments participated, but the Ukrainian nationalists were the most brutal. Yascha Nemtsov, Ibid., p. 10. ↩

Vladimir Lenin proclaimed in 1919: „Only the most ignorant and downtrodden people can believe the lies and slander that are spread about the Jews” Cf. Iryna Meleshkina, Research Director of the Museum of Theater, Music and Cinema in Ukraine, The history of Jewish theater in Ukraine, part 2, 2020. ↩

Myroslav Shkandrij, National Modernism in Post-Revolutionary Society: The Ukrainian Renaissance and Jewish Revival, 1917-1930 (pp. 438–448) in: Splinter Zones of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman borderlands, Indiana University Press, Bloomington 2013, pp. 443–448. ↩

Concentration camp operated until 1943, when Red Army conquered Kiev in the battle. More on that in: Ilia Altman, Victims of Hatred: The Holocaust in the USSR 1941–1945, Muster-Schmidt Verlag, Northeim-Sudheim 2008. ↩

Cf. Ruth Schweitzer, Ukrainian composer was banned in Soviet Union, „The Canadian Jewish News”, 2019. ↩

Here and below, see Yelena Zinkevych, Lyatoshinsky and Kyiv school, in: Ukrainian Music – Idea and history of a musical national movement in the European context, Gudrun Schröder Publisher, Leipzig, 2013, pp. 37–40. ↩

The „sixties” include, among others, Vitaliy Godziatsky (1936), who is considered “ultra-modernist”, Leonid Hrabovsky (1935), Volodymyr Huba (1938-2020), Volodymyr Zahortsev (1944-2010) and the internationally quite well-known Valentyn Silvestrov (1937), who worked in the style of „meditative postmodernism”’, Yelena Zinkevych, Ibid., p. 39 ↩

Yelena Zinkevych, The Ukrainian Composers’ School in the Socio-Cultural Context of the 20th Century, in: National Music in the 20th Century. Compositional and Socio-Cultural Aspects of the History of Music between Eastern and Western Europe, ed. Stefan Keym i Helmut Loos, Gudrun Schröder Verlag, Leipzig, 2004, pp. 155–164 ↩

Mihaela-Georgiana Balan, Polystilism in the Context of Postmodern Music. Alfred Schnittke’s Concerti Grossi, „Artes Journal of Musicology” 2021, no. 23 vol. 1, s. 148. ↩

Alla Zahaykevich, Українська електроакустичнамузика: Історія і сучасність’ (Ukrainian electro-acoustic music), in Часопис Національноїмузичної академіїУкраїни імені П. І. Чайковського. No 4 (Timeline of the P. I. Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music), Kyiv 2015, pp. 76-83. ↩

Myroslav Shkandrij, Avant-Garde Art in Ukraine, 1910–1930 Contested Memory, Academic Studies Press, Boston, 2019, s. 448. ↩

On the site of the Lviv Center for urban history, the history of the city of Lviv is presented in several digital histories and virtual walks. Among the most revealing stories about the city’s population and about concrete incidents and confrontations between several ethnic groups, including Ukrainians (formerly called Ruthenians) Poles, and Jews, include The General Regional Exhibition of Galicia (especially in the section Regional vs. National: The Discussion between Ruthenians and Poles section), Past, Present and Memory: Rediscovering Jewish Lviv, Life, Dreams, Fears: Literary Trip along Pidzamche. Depending on the region and city, the population consisted of different minorities. Also several German exclaves lived on the territory of today’s Ukraine until their expulsion after World Wars I and II. ↩

Myroslav Shkandriy, Avant-Garde Art in Ukraine, 1910–1930. Contested Memory, Academic Studies Press, Boston 2019, p. 12. ↩

Here and below: Vera Faber, The Ukrainian Avant-Garde between East and West, Verlag Edition. Kulturwissenschaften, Bielefield, 2019, pp. 9-30. ↩

Georgiy Kasianov, Wilfried Jilge, Vademecum – Contemporary History Ukraine. A guide to archives, research institutions, libraries, associations and museums, Institute of Ukrainian History of NANU, Berlin-Kyiv 2008, s. 16. ↩

Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Comparative Literature. Theory, Method, Application, Rodopi, Amsterdam/Atlanta, 1998, p. 20. ↩

V. Faber, The Ukrainian Avant-Garde, op. cit., pp. 29–30. ↩

(Edward W. Said, Culture and Imperialism, Vintage Books, New York 1994, p. 9. ↩

S. Tötösy de Zepetnek, Comparative Literature…, op. cit., p. 131. ↩

Oral citation Madina Tlostanova, online lecture The (hi)stories untold and the people erased: imperial difference, the cancelled socialist utopia and/in the global coloniality, occurred on 15.01.2021 at Aarhus University, Institute for Cultural Transformation ↩

Quotation by Ksenia Malych, translated from the interview by Hanna Mamonova Сучасне українськемистецтво – це територія розширених етичних рамок (engl.: Contemporary Ukrainian Art – this is the territory of the extended ethical frameworks), „Suspilne Media”, as of 09.04.2021. ↩

See Irina Tofan, 5 трендов украинского искусства за последние пять лет [5 Trends of the Ukrainian art in the last five years], Buro 247 – Online-Magazine, pub. 02.04.2021, opened on 23.06.2021. ↩