resistance marking compass

Cartographies of resistance, explorations of identity

An outline of contemporary Ukrainian sound art

When I asked a range of people who, in their view, is the “founding figure” of Ukrainian sound art, I received a wide variety of names and pseudonyms ranging from individuals tied to new media art to those primarily active within the quasi-academic sphere of contemporary music1. Different environments, different circuits, different forms of institutional anchoring—the genealogies of Ukrainian sound art are as diverse and heterogeneous as anywhere else.

What do we even mean when we talk about “Ukrainian sound art”? How do we define each part of this phrase? How do we outline the field and grasp the essence of sound art—is it closer to the Anglo-Saxon British tradition of sound art, or perhaps more aligned with the German Klangkunst tradition? Or should we frame the field differently altogether, moving away from external, Western European concepts and discourses? In the context of sound art, are we interested in certain peri-academic musical compositions that venture into spatial, multi-speaker music, or in visual artworks enhanced by an additional sound layer, starting, for instance, with paintings accompanied by composed music or spoken text? And what about video works and their audiovisual nature, or (post?)conceptual pieces that engage with sound or listening?

On the other hand, Equally, does this question concern sound art “created by individuals holding Ukrainian citizenship” (including members of the Ukrainian diaspora), or rather works that were “created (and perhaps even exhibited or performed) on Ukrainian territory”?

In the following text, I have tried to approach the subject broadly, including works and activities that function on the ground of include a variety of various disciplines and arts. This is barely a preliminary field mapping; it is a sketch open to further development and additions. deepening the marked threads. At the same time, I have constantly tried to balance the work being produced in Ukraine today and the work of artists who are currentlyare as well as projects of figures currently co-creating Ukrainian cultural life outside the country.

The ventures (concerts, exhibitions, festivals, residencies, fellowships, individual works, etc.) are often carried out under the auspices of at many institutions at the intersection of musical life and the visual and/or performing arts, which operate in parallel in the country and abroad. Initiatives, such as the Kyiv Biennial, have become international umbrellas for promoting contemporary Ukrainian art, acting as a “hybrid” (both here and there), and connecting and networking networks of individuals and artistic communities. This also activates the contemporary Ukrainian diaspora, and the events themselves are part of international cultural policy.

Sounds of war

“In wartime, the primary human sense is hearing. You yourself are literally transformed into one big ear,” wrote Liubov Morozova2. Today, with the third anniversary of the full-scale invasion by the Ruscism regime behind us, the war soundscapes and the experience of listening to military sounds lie at the heart of contemporary Ukrainian sound art.

The shocking work Repeat After Me II by Open Group — widely discussed and exhibited, including at the Polish Pavilion of the Venice Biennale (and, as I finish writing this, at Warsaw Zachęta Gallery) — directly addresses the experience of wartime listening. It is an audiovisual video installation in which civilian refugees recount their experiences by mimicking environmental sounds they heard during the full-scale invasion. In an eerie, tragic form of karaoke, they invite the audience to repeat the same sounds, guided by peculiar textual scores based on the artists’ literal interpretations of the rumbles, swishes, and other sounds of wartime danger. The experience depicted is fundamentally incommunicable and untranslatable — only radical, artistic translations or approximations are possible, breaking down language in a tradition rooted in Futurism, Dadaism, Constructivism, and Concretism. The situation is at once tragic and absurd.

Repeat after Me II, installation view, Polish Pavilion Biennale Arte 2024, photo by Jacopo Salvi / Zachęta archive

For years, discussions within the performing arts have debated the possibility of conveying experience through recorded media. Repeat After Me II stands out as a powerful artistic argument for the importance of the personal transmission of experience. At the same time, many art projects focus on building sound archives based on field recordings and other captures of the auditory landscape —such as Alevtina Kakhidze’s visual diary, in which the artist graphically mapped the directions of artillery fire she heard in February and March 2022 from the Muscovite suburbs of Kyiv. Both these works highlight how varied documentary formats can be: people themselves can serve as living archives, just as recordings can be vital documentation of experience.

From the perspective of sound art theory, we can distinguish two non-exclusive, complementary aspects at work. Firstly, the archival-documentary side of artistic activities that orients towards constructing collections that may look like the bringing together of audio fragments or series. Secondly, the impulse to create a sound monument, an artistic interpretation of the surrounding reality. This may present itself as a narrative framework, highlighting a selected issue.

Nowadays, the memorial and the archive are the two fundamental figures of audio memorialization (personally, I prefer to use the term audio memorialization). They often complement each other and work on different levels of projected meanings of artistic creation—both in the context of references to the distant past and “hot” commemoration of events and contemporary figures.

The same can be seen in the Ukrainian sound art scene. Streams and maps become audio testimonies. The sound archives are an auditory documentation of the violence, but also a testimony-memorial to the resistance of Ukrainian culture and society. In this context, the collaborations and cooperations around field recordings, as well as their archives and streaming, have become particularly notable. Field recording has become a key media of contemporary Ukrainian art today, the basis of activities such as the multi-collaborative streaming project Soundscapes. Listening.:

- Museum of Modern Art of Odesa;

- the independent organization Righteous Rechi;

- past / Future / Art platform dedicated to cultural memory;

- soundcamp artistic cooperative;

- acoustic Commons international initiative.

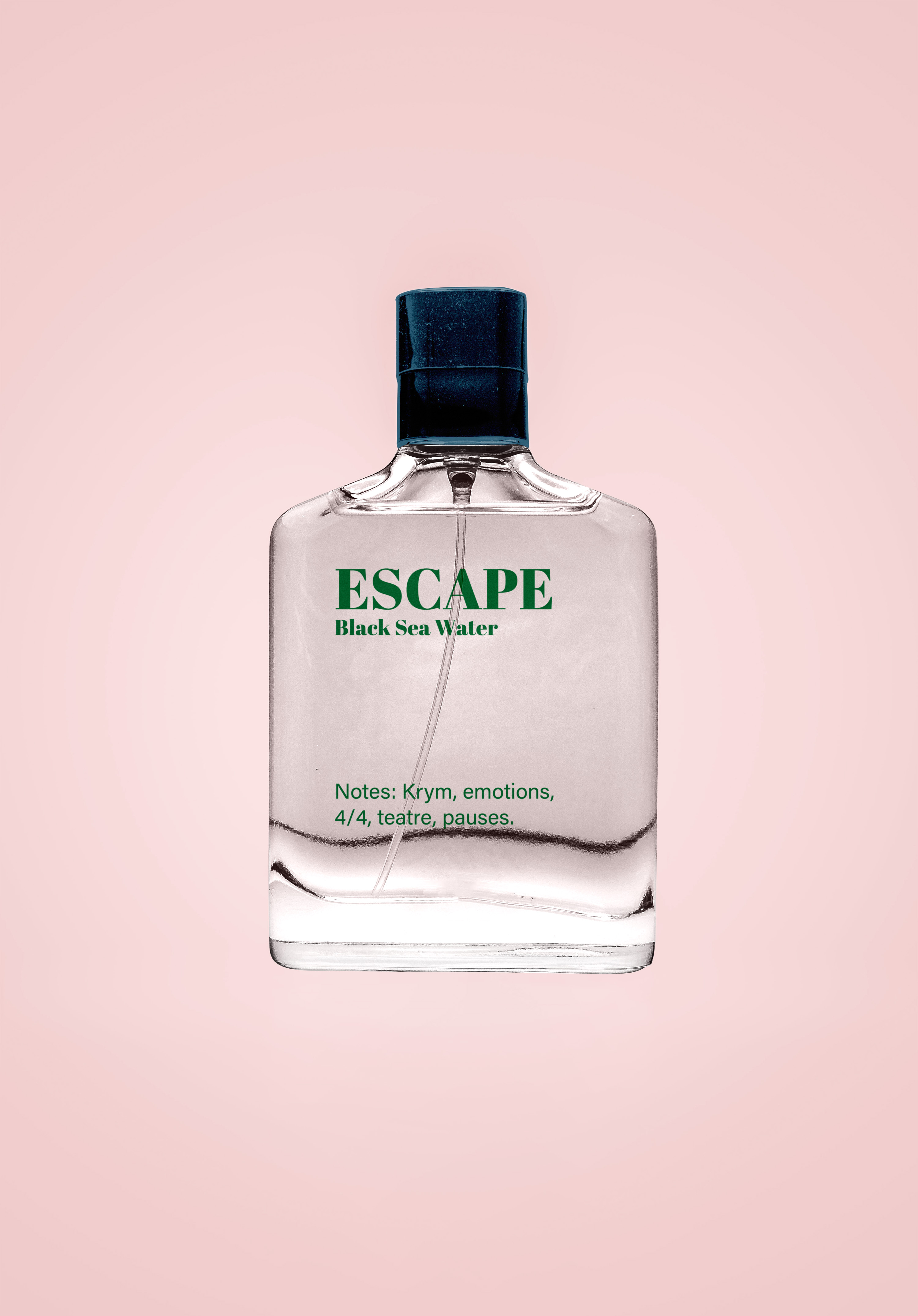

In exhibitions and presentations of this kind, auditory cartographies are largely shaped by curators. The act of connecting the dots that form the sound narrative is developed and expanded. Personal experiences stand in for places, collectively composing the map as soundscapes.. Listening originated from an idea conceived a few years ago to capture the changes in the auditory landscape along the Black Sea coast. Over time, however, it evolved into an aural document of the transformation of soundscapes and the broader environmental impact of the full-scale invasion, becoming part of the larger Land to Return, Land to Care project, which is dedicated to various artistic reworkings of wartime experiences. The five artists involved—Maxim Ivanov (Dnipro), Viktor Konstantinov (Odesa), Kseniya Shcherbakova (Kyiv), Ivan Skoryna (Kyiv), and Kseniya Janus (Uzhhorod)—represent different locations across Ukraine and bring with them distinct and different experiences of the war.

The recordings engage different types of memory and various layers of identity for the participating artists3. They are unified through the activity of walking , collectively weaving a rich fabric of wartime daily life soundscapes. The resulting sound archive has found a physical home in a dedicated listening space called Home of Sound in Lviv. This institution has become a hub for discourse on sound studies and sound art, as well as a venue for site-specific artistic projects exploring acoustics—such as the Graphic Improphase concert: Presentation by Ostap Manuliak (10.05.2024).

Another series of record-based installations was curated by the Ukho Music Agency collective, juxtaposing the sounds of Kyiv before the war with the city’s current audio landscape. . Memory captured in recordings dating back to 2011 is contrasted with various elements of the current soundscape, forming the core of the audiovisual installation Kyiv Eternal by Oleh Shpudeiko (Heinali). Meanwhile, archives of recordings from 2022–2023, arranged into an auditory map, form the basis of Ian Spektor’s Death in June project. The entire series of Ukho Music Agency installations has been further enriched by the addition of a selection of home and private recordings from recent years4. Notably, Kyiv Eternal was released as a narratively structured album, and the release of Death in June is planned through the Ukho-affiliated label kyiv.dispatch. These two different narratives about spaces of memory sit at the intersection of auditory cartographies and psychogeography, and have been translated into media that can be potentially carried anywhere. The works clearly reflect an urgent need to respond to the impulse to archive fragile and endangered sonic worlds.

The wartime audiosphere demands to be voiced or shouted. This is clearly demonstrated by artworks that have been, in a sense, secondarily expanded with an auditory layer—such as the sculptural installation I’m Fine, created for the Burning Man festival by the Ukraine Witness initiative, to which a sound component was later added during the festival by Vitaly Dejnega.

Leslie Khomenko’s paintings of her husband, Maks Robotov (who serves at the front), based on his photographs, have also been exhibited together with his noise music in venues such as the Labyrinth Gallery in Lublin.

Testimonies also take the form of archives or collages of statements, stories, and speeches. This is evident in the sound installation created by the Secondary Archive platform (a network-archive dedicated to women’s art in Central and Eastern Europe) for Manifesta 14 in Pristina (2022), which was later presented in Warsaw. The network gathered contributions from fifty Ukrainian women artists at the Kosovo Biennial, with fourteen of them producing sound works that were showcased not only at Manifesta, but also at the Warsaw Observatory of Culture (WOK)5.

The documentary aspect of works based on speech and text can, of course, be mediated;testimonies can be processed, transformed, translated, and reinterpreted. This is the case with Alisa Kobzar’s composition The Ocean I Am, largely constructed from the texts of Maria Kalesnikova, a Belarusian activist and prominent instrumentalist imprisoned by the Lukashenko regime, and Vasyl Stus, a Ukrainian dissident poet and key figure of the shistdesiatnyky movement. The texts, interpreted by Viktoriia Vitrenko, form part of Kobzar’s electronic, spatial composition, which has at times been presented in installation form, utilizing a multi-walled, multi-directional, and multi-channel speaker-sculpture, among other setups, at the Audio Art Festival in Kraków. In this work, the artist creates a kind of “subjective collective consciousness”6 immersed in electronic sounds that overflow between different channels—drenched in the sonic sea of memory and identity. The texts, as interpreted by Vitrenko, occasionally emerge from the depths of thought, as if floating to the surface of consciousness.

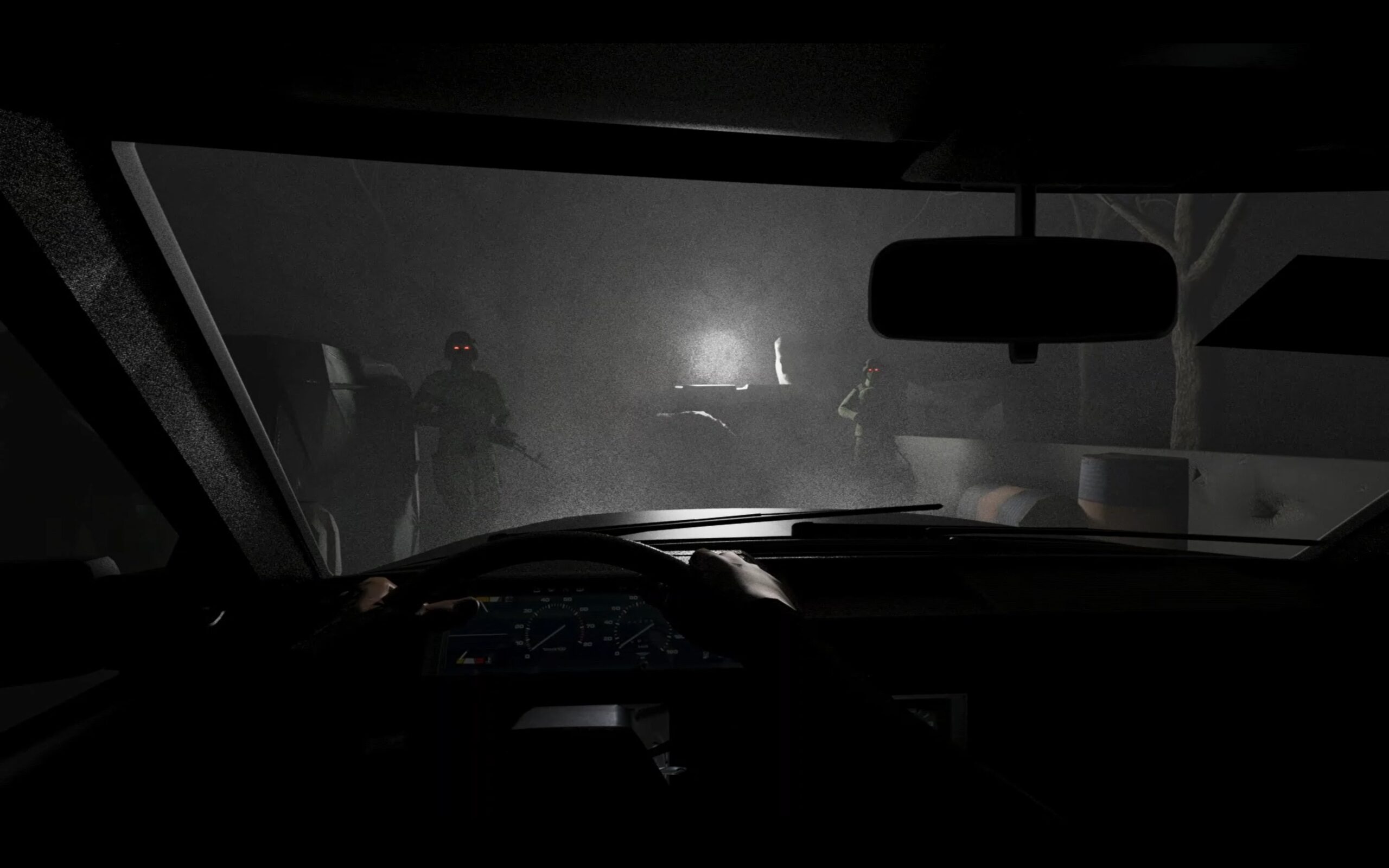

A sound document can be created almost involuntarily, for example, Sashko Protyah’s documentary My Favourite Job, which follows people heading behind the front line toward Mariupol in the spring of 2022. The documentary’s sound layer is a crucial, though potentially retraumatizing, dimension. As a result, when the film was presented as part of an exhibition during the Survival Art Review in Wrocław (2023), I also experienced it as a sound work. I was particularly pleased with the placement of the work—displayed in a separate room, not far from other pieces with a loud, audible layer.

My Favourite Job (2022), directed by Saszko Protiah

Sound commemoration, in contrast, can involve not just the recordings themselves but also the objects associated with them. An excellent example of this is Zhanna Kadyrova’s Instrument (2024), an organ constructed largely from repurposed Ruscism shells. Produced in collaboration with the Pinchuk Art Centre, the work is a sound sculpture-instrument in the tradition of the Baschet Brothers and Harry Bertoia. The instrument is part of a broader series of works by Kadyrova based on objects that bear the marks of wartime destruction (see the exhibition Unexpected), yet it carries a monumental dimension. It functions almost as an installation-monument, while also serving as a manifesto of contemporary Ukrainian culture—a work born of violence but creatively repurposing its remnants.

Identity

A significant portion of contemporary Ukrainian sound works is focused on exploring Ukrainian history, culture, and identity. These works are also, to some extent, connected to the war and primarily in the context of the broader imperial conflict waged by the Ruscism regime against Ukraine’s culture. The struggle for cultural independence is one of the key sectors of the cultural frontline in this war. Ukrainian institutions, alongside intellectuals and artists, are actively working to dismantle outdated Russian imperial narratives surrounding Ukrainian culture. As a result, one of the central themes of contemporary Ukrainian cultural policy has become positioning Ukraine and its culture within post-independence, colonial, and post-colonial discourses. In the realm of music and sound studies, this issue is being explored by figures such as Anna Kwyl at the Institute of Sonology at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague, among others.

Cultural institutions today are increasingly using sound as a tool to shape exhibition narratives, blurring the lines between sound design and sound art installations. International exhibitions have become a particularly significant instrument of Ukrainian cultural policy in recent years—both domestically and abroad. As a result, much of the work in question has been displayed where Ukrainian cultural policy institutions have directed their efforts. Many of these exhibitions are also accompanied by specially composed works that lie on the border between contemporary or independent music and post-ambient sound design. For instance, for the traveling exhibition Ukraine In Miniature, which showcases the country’s cultural heritage, a sound layer was composed by 29 (!) composers, musicians, and sound artists. The exhibition, built around 3D models of selected monuments from various Ukrainian cities, features these compositions as ambient soundtracks, while also attempting to create a musical dialogue with the architecture7 . You can also listen to the show online.

It is impossible to cover all the compositions here, but it is worth highlighting a few approaches to creating a sonic relationship with selected places. Some of the invited artists chose to make references to folklore and folk traditions (e.g. Zoltan Almashi, Jehor Litvinov), while in some electronic compositions, one can hear allusions to specific aspects of certain places (e.g. Olesia Onykijenko aka NFNR, Sashko Dolhyj) or the use of field recordings (e.g. Veronika Kanishcheva). Hanna Bryzhata (The Bryozone Project) created a fictional soundtrack for a computer game about the so-called Vitautas Tower in the Kherson region. I was particularly struck by Yana Shliabanska’s piece, which is dedicated to the water tower in Vinnytsia, an iconic part of the city’s soundscape that functions as a clock. Shliabanska’s composition is based on the deconstruction of the sounds of the city clock (ticking, bells), crafting a rhythmic structure from gently murmured sound artifacts and alluding to how the tower shapes the rhythm of social life.

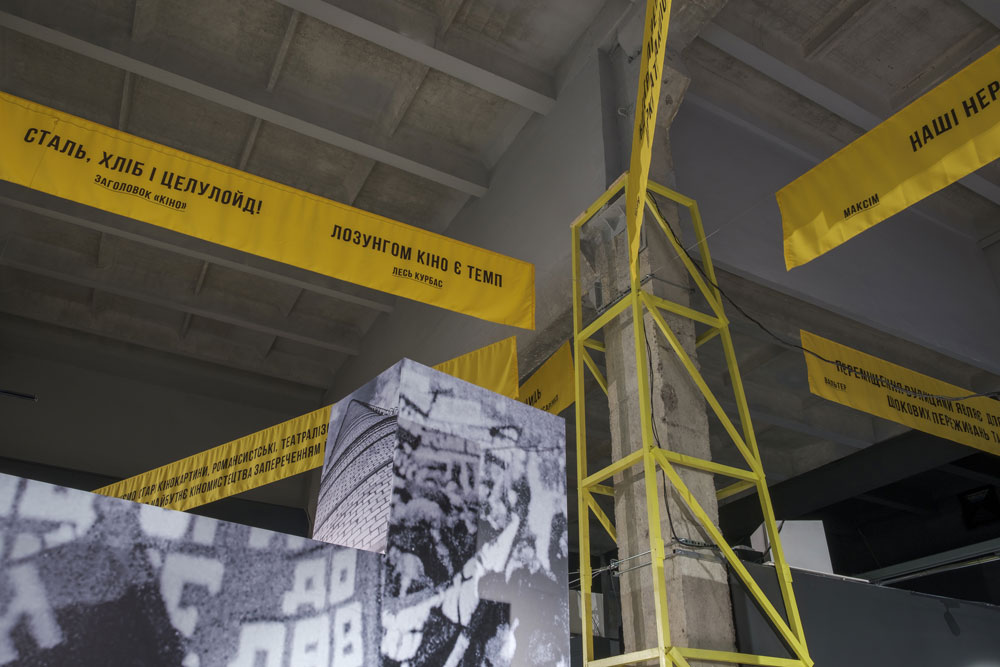

A similar example of composing the auditory layer for an exhibition focused on cultural heritage is the collaboration between George Potopalsky and the Dovzhenko Film Centre. Potopalsky created an installation exploring the sounds of modern metropolises, which serves as the sound backdrop for the section of the exhibition dedicated to film depictions of the city and urban life in the 1920s and 1930s (https://vufku.org/en/vystavka/the-city-drugs-and-the-cinema-2/). Furthermore, by expanding the existing music of Yuli Mejtus for Kira Kiralina (1927) by Boris Glagolin, Potopalsky, together with Alla Zagaykevych, also created a sound installation exploring the sonic breakthroughs in cinema.

Installation “The City” by Georgij Potopalski

The entire exhibition reinterprets the history of the Ukrainian film industry within the context of the Soviet transformation of interwar culture. Contemporary sound installations act as modern sound essays, redefining established narratives and shifting focus, attributing causality to key figures in the films of that era while reconfiguring the narrative framework. This is just one example of the contemporary museum-decolonization narratives emerging in cultural institutions across Ukraine today.

Beyond “localness”

Placing the category of “localness” issues like cultural identity and current struggles at the heart of creativity raises concerns about the potential for art to be excessively pigeonholed and reduced to selected narratives.

When searching for sound art that explores diverse themes, one will encounter a wide range of projects involving the aforementioned Alisa Kobzar—a composer, sound artist, designer, and game programmer affiliated with Graz University. Kobzar is a versatile artist who embraces transdisciplinary and collective projects, including sound works. In her pieces, she addresses themes such as migration, the Anthropocene, and climate catastrophe (The Anthropocene Maze, private network), while also creating abstract, resonant sound spaces. She tackles some of the “universal” themes of today as well as creating works focused on sound, listening, and architecture.

Understandably, migration is a recurring theme, and here personal experience intersects with one of the most urgent topics of modern times. . It can be found, for example, in Anna Chwyl’s auditory walks, Kyiv—Den Haag—Kyiv—Den Haag (2023) and Still Present As You Notice Its Absence (2024), in which the artist problematizes her position as an immigrant listening, so to speak, “from outside” Dutch cities.

An important strand of experimentation with autotelic sound art over the years has been rooted in Ukrainian independent music, particularly electronic music. The Kvitnu label played a significant role in this, with Dmytro Fedorenko (formerly Kotra, now mainly Variat) and Kataryna Zawołoka (Zavoloka) leading the charge. The best testament to Kvitnu’s conceptual approach to electronics and sound in the digital age is not necessarily found in the label’s impressive catalog (which included albums by Pan Sonic and Muslimgauze), but rather in its most recent release: SILENCE (2020), a work filled with silence and an endlessly looping structure. The core of this release is not the sound itself, but the accompanying artistic manifesto by Kotra and Zavoloka, which frames the silence as the primary content.

Similar aspirations toward sound art that treats sound itself as an artistic material can be found, for example, in the spatial compositions of Anna Arkushina, Anna Chwyl, and Jana Szliabanska, as well as in the concert-sound art activities of the Lviv-based House of Sound mentioned earlier. A key figure in the development of this type of multichannel composition has been, and continues to be, Zagaykevych.

Significantly, some works have been recontextualized by the artists, who have infused them with new meanings in response to their own experiences. I mentioned this earlier in the context of the Soundscapes. Listening project. Another example is Stay in Touch by Maryna Khrypun and Valerie Karpan (2019–2023), which has evolved over the years in Wrocław. Initially created as a tactile object—a table designed to convey trans-sensory and trans-media stories about contemporary urban life—it serves as a kind of haptic interface embedded in a work of visual art, but operating through auditory narratives. The emphasis was on inclusivity for the blind, positioning the haptic-auditory experience within the realm of non-normative listening (aural diversity). The object itself, a table-sculpture-interface, was created in collaboration with the MiserArt Foundation, which works with people who have experienced homelessness. It wasn’t until the full-scale invasion that recordings from various Ukrainian locations were integrated, adding an audible layer to the work. When the interactive installation was exhibited at the NFM during the 20th WRO 2023 Media Art Biennale, these new contexts strongly shaped my perception of the piece.

Meanwhile, the idea of a multisensory, interactive installation, i.e. an instrument-interface operating a thoughtful library of uploaded sounds, is striking in the long run. A similar approach can be found in the collective soundart work by Shliabanska, Tetyana Khoroshun, Liuba Plavskaya and Ostap Kostyuk VERBOVA (2018). In it, the composer has created a spatial, perhaps topophonic, multi-speaker interactive sound installation—a kind of environment in which the audience moves on unfolded planks of bark, triggering processed recordings from the forest of the “Holosiiv” National Nature Park in Kyiv. In this case, as “local” sounds as possible have been used for a self-reflection on the sound of the digital age—processed and trimmed and then arranged into “tracks”, just like the wood used in the work. It’s a work that is rather in dialogue with the classic (proto)sound art works of conceptualism, headed by Robert Morris’ The Box with the Sound of Its Own Making.

Ukrainian culture is constantly engaging with today’s “great” and “universal” themes, exploring various media, forms, and arts in a modernist fashion. However, for more than a decade—and especially since February 2022—this exploration has been inherently influenced by the looming prospect of war. The total scale of Russian aggression—rooted, among other things, in the denial of Ukrainian culture—means that every sound work becomes, so to speak, “mobilized” as a testament to Ukrainian culture from its very inception.

The most common responses sent by a group of people you know: Ujif_notfound, V4w.enko, Ostap Manuliyak, Alla Zagayykewyczh. ↩

Lijubow Morozowa, Podczas wojny zamień się w słuch, tłum. Agata Pasińska, „Ukrainian Corridors”, „Glissando”,,, httpuc.glissando.pl/pl/podczas-wojny-zamien-sie-w-sluch/, accessed 07.08.2025 ↩

One key issue, for example: did the person stream from a place they consider to be “home?”, or did they have to leave “home” as a result of Putin’s actions in 2014, or after a full-scale invasion? ↩

See: https://docudays.ua/eng/2024/news/oglyad-programi/slukhayuchi-vidsutnist-zvukovi-arkhivi-nesporozhnilikh-kimnat-/ ↩

Jana Bachynska, Tereza Barabash, Osana Chepelyk, Olia Fedorova, li Golub, Kseniia Hnylyctska Alewvtin Kakhidze, Tetiiana Kornieievva, Yulia Kosterewva, Yulia Krivvicz, Mria Kulikowvska Anna Manankina, Valeriia Troubina, Anna Zwvagictsew. ↩

Phrase for: akobzar.mur.at/installations/oceaniam/. ↩

Significantly, very interesting compositions on the most up-to-date topics possible (including, for example, Excerpt from the Earth Diary by Kobzar ), were created, for example, as part of the Pandemic Polish-Ukrainian Media Space project. The project provided the impetus for sonic explorations focused on health, the body, or even isolation, as well as wider issues such as. ecology and even the global economy. A significant portion of the Ukrainian participants of the project prepared works that span contemporary music, experimental electronics and sound art. ↩