Composer Tamagochi

Creativity is my inner pitchfork. Interview with Maxim Kolomiiets

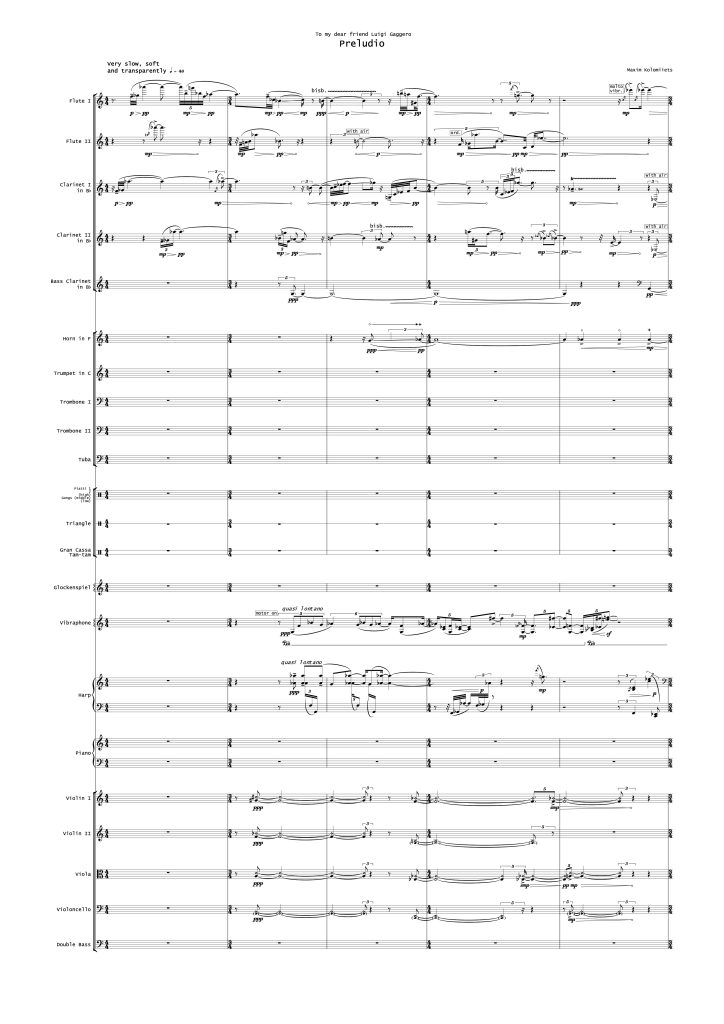

The famous Ukrainian composer and oboist, co-founder of the iconic Ukrainian contemporary music ensemble Nostri Temporis, Maxim Kolomiiets, is currently in Germany, where more than 10 of his works have premiered over the past six months. Here, Maxim also organizes Ukrainian music concerts and tells journalists the uncomfortable truth about the war that Russia has unleashed in Ukraine. In our conversation, the composer explained how he creates the hermetic world of his music, how he works with emotions, and that honesty in creativity is related to a social stance.

Stanislav Nevmerzhytskyi: Recently, you adapted a piece Under skyline, which was performed in 2012 on the territory of the former insulation materials plant “Izolyatsia” in Donetsk, for the Ensemble Proton Bern. What are your memories about this unusual art space, which since the beginning of the Russian-Ukrainian war in 2014 has been transformed into a torture chamber by the terrorists?

Maxim Kolomiiets: It looked like an ordinary Soviet factory, which the owners decided to transform into an art space. It was no longer functioning, but some employees continued going to work – at that time they were asked to assist the musicians, so that’s what they did.

We could do whatever we wanted, even if it looked strange. For example, we decided to saw huge metal sheets and hang them on large hooks. Why would anyone do this? The workers didn’t ask, but patiently sawed the sheets and hung them.

The performance took place in several locations. A brass quintet was located on a railway platform at the entrance to the administrative building. A solo flute played in the middle of the waste piles. Finally, we played in an iron cage with the ensemble.

Composer Bohdan Segin played in the pavilion, and guitarist Dmytro Radzetsky played on the top floor of the administrative building. There was a video projection from the top floor onto a huge factory pipe. It was fun.

The new version of the work reflects the painful changes in the role of this space. Is this somehow revealed in the musical language?

I have always tried to create a hermetic world in my works, which can be transferred to other instruments or to another space. The problem here was that everything changed – the instruments were completely different, as well as the space and acoustics. So, it was impossible to simply transpose the notes.

In Donetsk, your goal was to fill up a huge space with sound…

The goal was different because the work was performed open air with sound amplification. The idea was to do something like an outer space with the music dissolving beyond the horizon.

For the Ensemble Proton Bern, however, the goal is to create something more academic and traditional. We have a concert hall, an insulated room, a kind of incubator, where music is adapted to this space. This is a completely different task. I had to work on making a good version of a conventional academic piece.

The process of “transposing” a piece from one instrumental ensemble and site to another is a big tectonic shift for musical material. How much did this influence the idea of the piece?

Of course, it had an immense impact – basically, it was impossible to keep the original idea. For example, the pianissimo performed by the brass quintet [as in the original – ed.] is very different from the pianissimo of the woodwind quartet [Proton Bern composition].

Moreover, the wind quintet is a powerful ensemble that creates a feeling of unrevealed force. The wooden quartet is a completely different set of instruments: they cannot play anything louder than the mezzo forte; the timbres vary between each other, and the sound density is different. Therefore, the concealed force of the brass quintet was impossible to reproduce.

We had to invent something new. So, we had to create completely different relationships and dialogues which did not exist in the first version at all, instead of a soprano part, which was juxtaposed to the brass quintet. Eventually, it became a different piece, based on the original musical material.

But you said that you create some kind of hermetic world in each work that can be transferred to new spaces. What parameters ensure its unique identity?

I said that it is a hermetic world, which can serve as a basis for creating something new, in order to discover new dimensions by pushing its boundaries. As for this work, it remains expansive, there are many very long notes.

We can think of the first version as the world of dinosaurs, which is observed from the position of the dinosaurs themselves. In the second version, we look at the world of dinosaurs from the position of the mammals that crawl among these dinosaurs. Basically, it is the same world seen through different eyes.

Do you think that the composer must invent a new language in each new piece, or work on one style, trying to improve it?

This is a good question. I once discussed this topic with a composer colleague. I believe that one needs to constantly reinvent oneself, create something new in each work, reevaluate what you did before, and try to reach a new quality or a new level. In contrast, my colleague said: “What’s wrong with remaining yourself? For example, [Olivier] Messiaen never tried to reach a new level – he always remained himself. We can recognize Messiaen’s music from the first chord of any of his works.” In fact, these are just two different approaches to creativity.

Many composers follow this approach of refinement of their means of expression – I see this among many contemporary composers, such as Beat Furrer or Bernhard Lang. But I am simply not interested in this. Let’s say I’ve developed a style in this particular piece, where long notes go on endlessly and a certain mood or emotional state is achieved by means of stasis. This sounds interesting for the first time, but then you need something else to continue being interested. It’s boring to sit on these long notes and not to search for anything else. So, these are two different approaches, and each composer chooses their own.

To some extent, the composer’s choice to work in a single style is determined by his or her own creative nature and the practical side of musical life – one needs to be approachable and predictable for the organizers of festivals, competitions, and ultimately for the public. On the other hand, an artist who chooses the path of creating something new is doomed to confront their previous self. Would this cause a certain resistance and doubts whether a particular approach or a theme has happened before while working on a new work?

I’ve been thinking about that lately. Living in Germany, I’ve been observing how others are working. I have noticed that some of the current trends do not interest me at all – not because they are bad, but because I have a different agenda. I agree with you that when a composer works on honing his or her style, it often happens because they live in the modern-day media space. Festival or concert curators who commission works always want to know what to expect from you. Anyone who orders a work from Philip Glass or David Lang will certainly know what style it will be composed in, and this is convenient for those who curate concert or festival programs.

That’s fine with me, but I have realized that I write music that should be attractive first and foremost to myself, music that would not let me get bored. Maybe it will not get where I want it to be – that’s too bad – but otherwise I am not interested. Otherwise, I would become a slave to this system, where you must write only what is expected.

Do you think that this situation might be a consequence of the specific situation in Ukraine, where composers are left to survive on their own, without any commissions and performance opportunities, where all they can do is entertain each other with their own music?

Yes, I have matured as a composer in Ukraine – and this situation seems both funny and tragic at the same time. In Europe, I see that there is interest in music, performers commission works, composers are in demand – this is a normal situation. In Ukraine, however, it seems surprising when someone is interested in your music, apart from yourself or your narrow circle of colleagues. I still can’t get used to this. This situation is really a vestige of the Ukrainian realities, and it influences creativity.

I think: “Well, if others are not interested, at least I’ll be interested.” This is a starting point for me, and I don’t see anything wrong with it. Even if I do not get closely integrated into this system in Europe, I will create something that will be valuable to me. In any case, I really like where my own work stands today.

Can you give an example of a piece in which you worked specifically on inventing your own language?

Espenbaum is an example of a work that I composed completely for myself. It is related to a tragicomic situation. The concert organization Ukho commissioned me an opera; when I wrote it, however, it was no longer needed.

Once I realized that the opera would not be performed anyway, I started focusing on the things that were important to me. Basically, it is an aria. The plot of the opera may be weak and static, but the opera does have a plot. The main character stands in front of the river and realizes that his life didn’t go as planned, just like Celan felt in his time [some parts of the opera were composed to the texts by Paul Celan].

What we have is a landscape and an experience of the protagonist’s tragic past, and his thought that he is about to end his life, and the feeling of frozen stillness.

How is this reflected in the music?

Technically speaking, Espenbaum in the opera begins at the end of the previous aria, built on the growling of Celan’s text. This growling is taken over by the orchestra in the next aria; it is dynamic, gets louder, and climaxes. And then it gets transformed into a piccolo flute solo, which is interrupted by woodwind passages. Overall, a fragmented drama, which is confined by the frozen and uneventful moment. It is a kind of landscape that begins with mountains and ends simply with the horizon.

So, it is a musical embodiment of the human condition before committing a suicide. It is hard for me to imagine what one needs to feel in order to embody this in music…

In fact, this is my condition, which would not leave me for the rest of my life.

You mean – depression, suicide…

Yes, this is my natural condition, I think about it all the time. But please understand me correctly: I do not have a constant desire to commit suicide, that is not what I am talking about. Once I was ready for it, but certain circumstances did not allow it to happen. Yet I do think about it all the time. Actually, any insightful person who contemplates complex ideas thinks about this in one way or another.

Do you communicate your psycho-emotional state through music?

I would not exaggerate the significance of channeling my current emotional state into music. It’s more like traces of the emotional state of my past self, when I was still very young, around 15-20. But what is music for me now… I guess I do need to talk about this. For me it is important to feel the response of the musical material during the process of composing.

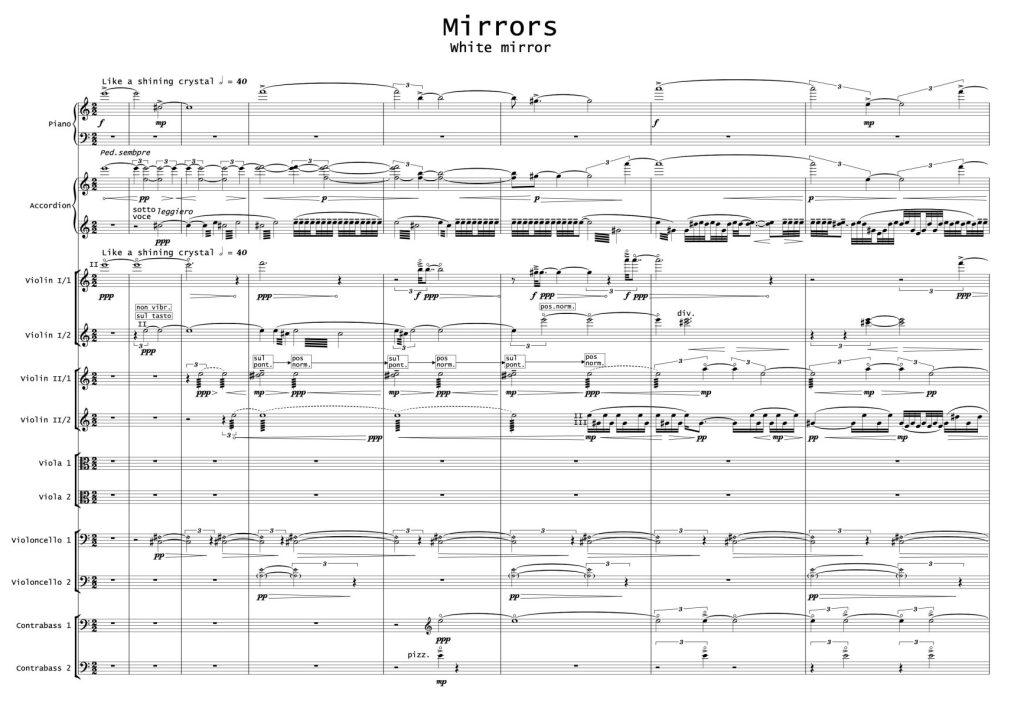

If I had to come up with an image for this, it would look like this: you create an ideal mirror and keep looking into it, trying to understand who you are, what you are made of, and what is your real essence. In this sense, I have been quite successful because now I understand much better who I am. This also refers to the fact that I am not much interested in making a career of a composer; rather, I am interested in what I create.

What does it mean to be a composer physiologically? Do composers get tired? How?

(laughs) To be honest, I hate working. It is difficult and exhausting, especially the revisions of an existing work. It is emotionally draining. Today, I would not say that my work is intellectual, because over the years I have already developed some shortcuts and know what works and what doesn’t.

It’s like playing an instrument – at first, it’s an intellectual process, when you have to think how to play the C major scale correctly, but when it happens automatically, the process is no longer intellectual, it is physiological … or rather an intellectual mechanism. It is an automatic process in which you are no longer thinking about the origins of your ideas, you are just writing and that’s it.

I am currently working on a concerto for two violins and orchestra. The most difficult thing is to discover the essence of the work, what emotion should guide it, and what you want to say… Once you find out what that emotion is, the rest is a routine operation, which no longer involves much reflection.

That is, the creation of a work emerges from an inner state, from emotions?

Yes, without emotions there is no need to even sit down to work – nothing is going to happen. In fact, it often happens that you start working, and then try to discover an emotion. Later, however, once you find the real thing, you will discard what you’ve done and start from the beginning. So, it is better not to work without emotions – it’s a waste of time.

How does the translation of this psycho-emotional state into music come about?

You have a set of devices that can help implement certain ideas. But in fact, if you have a complex emotion or image, it dictates to you which means to use, the means emerge from the very nature of the emotion.

I somehow thought that emotions were considered improper for contemporary composers…

Well, it depends on how we interpret the concept of emotionality. For example, I recently attended a festival where the Senza Sforzando ensemble from Odesa performed the music of contemporary Ukrainian composers. It was an interesting experience, because it’s one thing to listen to this music in Odesa, in its original environment, and another thing when you can compare it to the works of contemporary German composers. It was quite obvious: Ukrainian music is in fact very emotional, and it sounded very different from the German music that was performed next to it.

Emotion should not be contrasted to intellect. For me, intellect should follow emotion — a complex, rich emotion that you have to recreate, rather than just simply dispense into the score using simple techniques. It is precisely because these purely technical things can be quite complex, you can discover additional nuances in this emotion, make it more vivid and refined.

Going back to Espenbaum. Its emotion is this: what does a person feel at the end of life, sitting on the riverbank and thinking about broken, completely wasted lifetime? Emotion is not an impulse. It resembles the Kyiv landscape: large and small houses, roads, ravines, and rivers. It’s a complex nervous system that I have to realize in my work.

As a composer, how do you listen to music?

It’s a shame, but at home I usually listen to music when I’m doing routine work: typing notes or some kind of text. A couple of days ago, I re-listened to my playlist — what a collection! I have to admit that I don’t like much of new music, I like old music more, the one that is not related to academic music.

I have a selection of composers that I can listen to endlessly – Schumann or Bach – but the rest I listen to only when it’s necessary… I am currently writing a piece for piano. It’s been a year that I am working without an instrument, I can’t even check any notes.

I listened to a lot of piano music, contemporary and from the past, to look at technical ideas of other composers; as always, I didn’t like anything. In general, I rarely like anything. Therefore, I either listen to music I already know is good, or go to concerts, where it’s hard for me to be happy.

Are you annoyed by the quality of performance or by the music itself?

Everything annoys me. I don’t like that I can’t leave a concert when I want, that I have to listen to this exact music and this amount, that I can’t just rewind, and that the performance is somehow not right, or the seat is uncomfortable. In the middle of the concert, I can remind myself that I didn’t have breakfast, or start thinking how to get home afterwards… That is, all my thought would be not about music, but about running errands or other mundane things.

Why does this happen to me? First, it’s the performer’s syndrome. I am more interested in performing music than in listening to it; by performing, I feel in the right place. I worked in the theater for 20 years [Kyiv National Academic Operetta Theater], so I am used to listening to music while performing it. Second, in the 1990s in Kyiv, very few performances of contemporary classical music were held, so the only thing I could afford was listening to music on CDs. At that time, I developed a habit of listening to music the way I want – rewind, or repeat, if you like, make it louder, quieter, put it on pause. I developed a perception of music as something I can collaborate with.

Let’s rewind the conversation a little. You said that when you had to come up with a compositional approach while writing a piano piece, you turned to the music of other composers. Is this your natural creative method? Or did you do this only because of the lack of an instrument while writing the piece?

Any musical work, especially a masterpiece, is based on a number of ideas. Normally, it takes composers a long time to come up with these ideas – it may be thousands and thousands of hours of work, based on experience of less successful and unsuccessful works. It seems rational to me to learn from this experience. Many ideas are available to you – choose whatever you like. Even if your own piece is completely different, you can still consult the score and analyze why did a composer make specific choices notating their works, and what will happen if one writes differently? So, you can see the logic that guided a composer, trying to understand why specific devices are used.

You can build your compositional logic even on the basis of what is missing, rather than what actually was composed, and use these ideas as a starting point. As a result, my piano piece does not resemble any scores I have consulted. It is called City of Stairs; it was commissioned by the Ukrainian pianist Yehor Shevtsov, who currently lives in Norway.

What composers have influenced your music?

Of course, some composers and some works have, but it is difficult for me to talk about it now, because some of them have become a kind of compost, in a positive way.

Some composers have laid a foundation for all my further ideas and explorations, even though I don’t listen to their music anymore. They affect me even when I don’t listen to their music because I already know it too well and it doesn’t make sense to listen again. But there is a certain number of new works that are not connected to academic music. I find a lot of interesting ideas in the music that many composers do not consider serious, for example, I got hooked on compositions from some computer games. There are so many layers, the [composers of video game music] work with emotion in interesting ways, they use interesting sources, groove, beat, peculiar pitch combinations… The way this music is created is so cool, I am simply amazed!

We have already concluded that you are a “bad” listener – you are not satisfied with the concert setting itself, it is not comfortable for you as a listener – but do you think about your listener when you write your own music?

Certainly. No matter what I have said – that I write only for myself – I do work for the listener, and it is important for me to find a way to them, to share my feelings, to convey this emotion – this is very important to me. Because if everything was limited to writing for yourself, then I would not leave the room at all.

Before sitting down to work, you construct an emotional image. This image may be complex, heterogeneous, it may contain a plot. How can one describe the emotions of a composer whose country is at war?

In the first days of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, I had great doubts whether an author was even needed in such a situation if he or she cannot stop the war. Any soldier is more important in this situation than I – someone who just sits at home and generates some ideas.

Then I thought that if I let these emotions take over me, if they start to control me, then I have already lost my personal war. I cannot influence the course of the war, but I can resist losing my own. At that moment it was important for me to find something bright inside myself, to try to see it clearly and show it to others.

The first works I composed after the start of the full-scale invasion were quite bright – I saw your reflection in the river mirror and Waiting for the light, which was performed in Sofia Kyivska Cathedral. In the last one, the light appears for a brief moment, then disappears again, but we begin to live with the feeling that, after all, we have seen this light.

Another work, which I have not shown to anyone yet, is White Mirror. Back in 2010, I started writing the Black Mirror/White Mirror diptych. Black Mirror has already been performed several times in a version for button accordion with a string orchestra. I was postponing the composition of White Mirror for a long time. And then I realized – if not now, then when? This is also a very bright work.

Many Ukrainian artists ask themselves how they can be useful for the victory of Ukraine. What is your response to this question?

In Europe, there is a kind of vacuum with respect to Ukrainian music – it is very little known. Now there is no need to explain who Valentyn Sylvestrov is, but other contemporary composers are not familiar to the audiences. Even for the festival I was talking about, the ensemble from Odesa came only because the war had started. Before that, the organizers were going to invite another ensemble, where do you think they were from? From Russia, of course. They were going to perform Russian composers. Even in such a small town, we were losing. We managed to improve the situation with the performance of Ukrainian music slightly, and only because the war started, but this is only a drop in an ocean. We must have a million of such concerts [in Europe], I am not exaggerating. We should have many concerts of Ukrainian music of high artistic quality so that Europeans can say that they perform it not only because of the war, but because these are good works.

My contribution to victory depends only on myself – I have to create and promote good music. In fact, something like this is already happening: we are preparing a festival of Ukrainian music in Bonn, where Ukrainian performers will be invited. I myself will play in three concerts. This is my contribution.

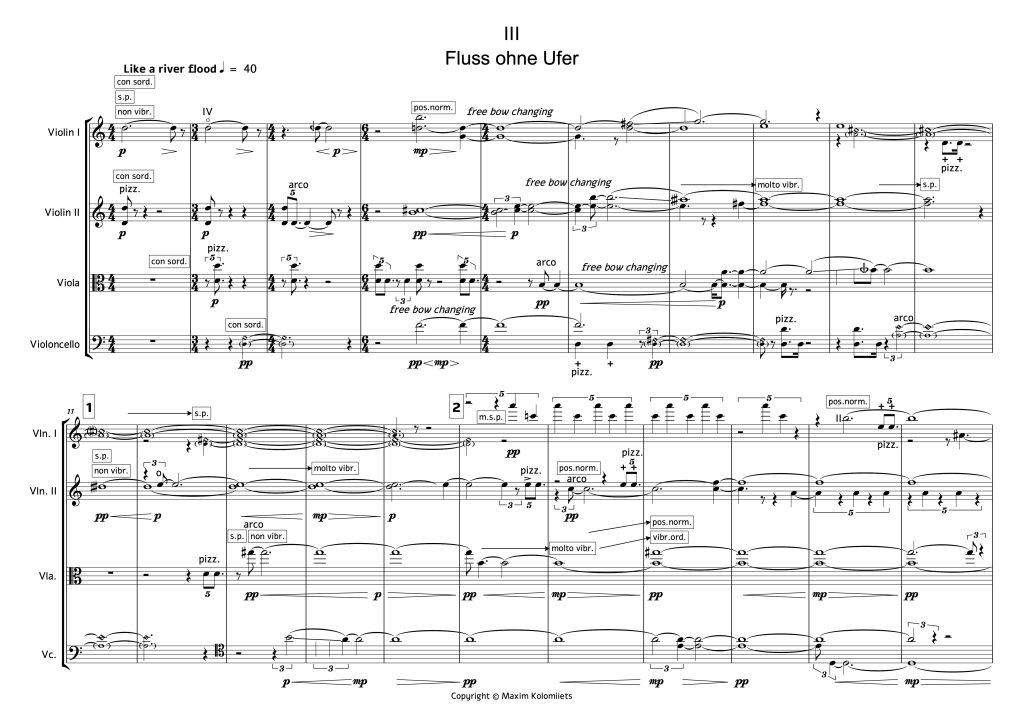

I have become very strict to myself and make more effort to compose at a high level, so that I don’t let Ukraine down. In fact, I have surprised myself by some of my recent works – they are truly the best I have written in years – String Quartet No. 2 and Mond und Steine on a poem by Serhiy Zhadan.

I give interviews in which I say things that journalists don’t always want to publish, such as the call to send more arms to Ukraine. “But this is an escalation of the conflict,” – some German journalists commented. Unfortunately, not everyone understands that escalation will happen precisely with the lack of weapons.

Can your creative work become the means of delivering the truth?

Creativity and music in a social context are rather multidimensional things. In some way, if you set such a goal, then it can become possible, but delivering the truth is not the most effective function of music. Can music work as propaganda? It certainly can. We can think that communism was a terrible thing, but on the other hand, Luigi Nono was a communist, so maybe communism is not so bad after all? Thinking that Nono was the supporter communist ideas, these ideas may seem less terrible.

It is better to simply be a composer with specific convictions than to channel your convictions directly through your music. Let’s look at an example of how our enemy works. There is a [Russian] pianist Valentina Lisitsa. She performs Chopin and is an outspoken supporter of the Russian world. She helps to build a positive image of Russian culture not because she plays Chopin, but because she is a very good pianist. That is, the Russian world is presented positively because of her high professional level, which has nothing to do with propaganda.

Is it natural for you to embody this combination of composer and performer with an active social stance?

An active social stance depends on how honest you are in your creativity and with yourself. Naturally, ideas that contradict your values will annoy you. When, let’s say, you protest against Yanukovych, you don’t do it because here is an abstract politician and here is your abstract idea of creativity; it happens because you have developed for yourself a certain vision, a benchmark of honesty that you yourself must meet. So, if you see that something unacceptable is happening in your country, you will protest, because your principles require it. You respond to what is happening around you, and it pushes you to the barricades.

Creativity is a reflection of you as a person. It is the inner pitchfork that resounds what I really am.

Тranslation: Oksana Nesterenko