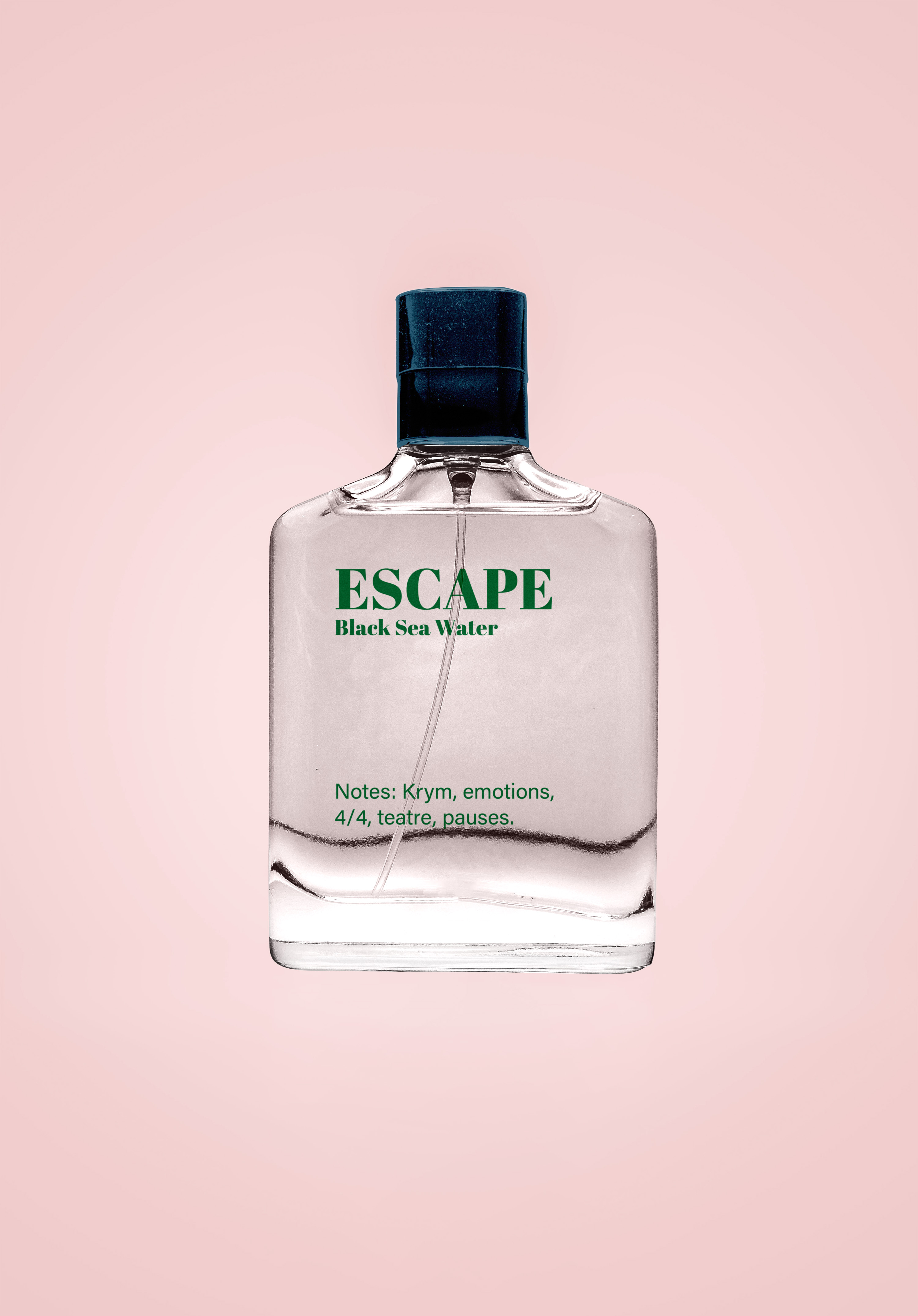

the essence of composing perfume

Zoya Mihailova: on dialogue with the audience

Solar Festival, Silesian Museum in Katowice, photo by Kacper Krzętowski

NP: The last time we spoke was during your preparations for the play Siedem historii okrutnych (eng. Seven Cruel Stories), directed by Justyna Wielgus and based on a play by Justyna Lipko-Konieczna. This is a unique play about human-animal relations showing a non-anthropocentric view of the world. How did the collaboration work?

ZM: In addition to composing and producing, I focused on creating surround sound based on projection channels in the simplest quadraphonic format. The premiere of the show took place in a non-theatrical space, in a large rented hall at Gen. Józef Haller Square in Warsaw, where we built the stage and sound from scratch. I wanted to make the perception of the audiosphere as realistic as possible and working with surround sound required me to rethink the existing structure when creating the soundtrack. Working with the group at the Kammerspiele in January 2024, during the Libido Romantico show, where I collaborated on a ten-channel speaker system, inspired me to experiment with separating layers of sound into different zones in the space, which added an extra dimension to each scene.

Siedem historii okrutnych, press photo, source: website Teatr 21

I developed my work with surround sound for Novika’s collective as part of the Sen maszyny (eng. Dream of the Machine) project in June 2024. This project, carried out as part of the BMW Art Club, consisted of two main elements: an ambisonic radio play in the garden, designed for ten speakers (the sounds were arranged dynamically – changing depending on the position of the viewer), and a soundtrack to a film essay presented as a six-channel sound installation. For me, these kinds of projects are a search for new forms of communication through sound and a desire to engage the listener.

Zoi Michailova and Maria Magdalena Kozłowska during the concert inaugurating the exhibition Sen maszyny (The Dream of a Machine) at the J. Słowacki Theatre in Krakow. Press photo, source: Słowacki Theatre website

NP: Theater 21’s announcement states that “the performance was inspired by Sunaury Taylor’s book, Beasts of Burden. Animal and Disability Liberation.” What does this essay mean to you? How has its content, which critically addresses the objectification and categorisation of the lives of people with disabilities and animals, influenced your approach to this art?

ZM: The book itself served as the starting point for the director and playwright to develop the script and establish a common thread for all seven stories. While working on the sound, I already had a broader and more specific idea of the structure of the show.

NP: This is not your first collaboration – at the beginning of the year you went on tour with a performance called Libido Romantico, which deals with the feelings, love and sexualities of people with intellectual disabilities. How do you work on sound when addressing such important topics

ZM: Libido Romantico is definitely one of my favorites when it comes to theatrical performances. It contains many authentic and intimate themes drawn from the real-life stories of the actors performing in the show, which are dramaturgically underpinned by specific themes from Adam Mickiewicz’s collection, Ballads and Romances. It is a manifesto based on a story from contemporary life concerning the perception of the love and intimate sphere of people with intellectual disabilities, and you can see the similarities within the works of the greatest poet of Polish Romanticism.

Working on Libido Romantico also gave me a lot of internal emotional stability and a sense of caring for each other, which was much needed during the period when we were creating the show – it was spring 2022, just after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

NP: Center for Inclusive Arts on Mickiewicz:

He spoke the language of the group with the lowest social status, giving them the right to embody their fantasies and desires. Filled with eroticism, sensuality and amorous frenzy, the texts also played an emancipatory role, becoming a manifesto of a new sensibility, abolishing class hierarchies and postulating a democracy of feelings. With his ballads, he introduced new, socially unacceptable images that hit hard at bourgeois prudery. Can his lyrics evoke similar anxiety today?1

How would you answer this question after composing music for a show inspired by his ballad?

ZM: Music only bolsters the message here. I think the answer definitely lies more in the texts/script based on real-life stories of actors and actresses. I could say more, but it would definitely be a spoiler for those who haven’t seen the show.

NP: How does acting in a group, particularly in specific projects, affect you, and how does it influence your approach to music?

ZM: Each collaboration unfolds differently, but they are almost always united by collectivity and the sharing of experiences. In the theater, I begin working with the director/dramaturg from the inception of the idea’s creation. I look for my own inspiration during this time, and after a certain structure is revealed, we sit down to work together to determine the shape of the soundtrack. Here, I work mainly with emotional and spatial associations while trying to avoid musical references because, in my opinion, they can have their own interpretation for each person based on associations, their own emotions and nostalgia. I record sketches and suggestions for seeing a scene, and then we choose which track we follow.

I really like to work collectively. With this kind of work, I work more with the context than with my own emotions. The same is true for performative, choreographic or visual formats.

I also love musical collaborations – in 2023, we created a musical project with Maja Kowalczyk, an actress from Theater 21 and saxophonist. Although it was a challenge of sorts (I’ll admit that I had some resistance to using an alto saxophone at first), we managed to play off its delicate, romantic sound brilliantly, processing and distorting it so that it sounded different – still romantic, but also glib. In 2024 Jerzy Rogiewicz invited me to create a joint project as part of the “Warszawo, Moja Warszawo” festival. I had an absolute blast playing together. George’s way of improvising and complementing each other’s sound, rather than emphasizing a particular musical part, allowed us to feel our synergy. I would like to develop these projects further.

I also work alone, for example, on Czy to pogłos odwiecznego świata? (eng. Is this the reverberation of the eternal world?) and individual sound works for exhibitions. Then I definitely involve personal emotions more in the creative process.

I also have a DJ alter ego and for the past eight years I have dedicated as much of my life to the club community as to the art community. Since 2017, I have been working with the queer-feminist collective Kem, where I co-organize and co-curate regular performance-music events at Dragana Bar. This collaboration means a lot to me. Kem events in the space at Podskarbinska Street (until the developer took over the area in 2018) were the beginnings of my playing and organizing events in Warsaw. At that time I also met Ola Osowicz, who offered me my first collaboration with choreography, after which we did Love is in the air in Wroclaw, directed by Aleksandra Osowicz and Matthieu Ehrlacher.

Transitioning between artistic and club reality gives me balance and helps me avoid burnout. When I feel tired of studio work and sound analysis, DJing becomes a springboard. On the other hand, the return to more introspective art projects, after the intensity of the night’s events, provides a sense of rootedness and opportunities to explore other forms of expression.

These two worlds also inspire each other. As a DJ, I work with the rhythm and emotions of the audience, connecting on a level of the here and now. In turn, working on art allows for a deeper contextualization of sound and narrative thinking, which enriches ideas for the structure of my DJ performances.

NP: When did you start working with sound? Do your works focus solely on sounds, or do they introduce dialogues between sound and other art forms, such as costumes, choreography or other visual elements?

ZM: I have held many jobs and worked in various industries throughout my life. I have a higher technical education. I used to work at the airport, but for personal reasons, I gave up a strictly technical profession. Until 2019, I also held so-called transitional jobs to support myself financially, until I was more or less well-established as an artist and could start living solely from my own creative work, such as music or playing at events. I also have a musical education, which was compulsory at my school in Simferopol. I finished piano class and also played guitar. My technical studies provided me with useful knowledge in understanding sound synthesis and DAW structure, as they were related to electronic devices in the aircraft cockpit and their software, and when composing and producing I work mainly on VST. I became incredibly excited and determined to work in music production after a workshop on Ableton production with Radek Sirko. What really appealed to me was his openness and experimental approach in understanding the technical issues of the whole process.

NP: Are your works always in dialogue between sound and other art forms?

ZM: My work does not always directly engage other art forms, but dialogue, both literal and metaphorical, is an important part of my approach. When I create in collaboration with other musicians, the dialogue takes place at the level of aesthetic and technical exchange, the sound becomes a field for tensions and contrasts, and opens up new possibilities for expression.

I also try to explore the multi-layered dialogue that occurs between music and its reception. Music in itself does not contain definitive content, it does not exist as an object without a medium such as a record or cassette. Its meaning is created in the context of reception – by the listening situation, the visuals or the emotions of the recipients. In this sense, each sound work is a dialogue with the audience, who, through experience, give it its final shape and value. This dialogue, whether it is between media, creators, or viewers, is an important aspect of the creative process for me.

NP: I visited the recent Alina Foundation exhibition titled Chimera, where your sound installation Sarcophagus could be seen. It was an extremely theatrical, even performative experience for me – you talked about the concept of the project on the fly, which added a unique vibrancy to the whole thing. At some point I felt that you were sort of a living part of the installation, an integral part of it – an actress, monistically connected to her work. Could you tell us more about this project?

ZM: Certainly, conceptual works are better viewed and listened to on an artist/curator tour, which took place at the time. However, I don’t feel it’s a performative contribution. For the exhibition Chimera.Wokół Alina Szapocznikow (eng. Around Alina Szapocznikow) I was invited by curator Karolina Wiśniewska, and the idea for the work went beyond the classical symbolism of the Chimera, exploring the boundaries between material and conceptual meaning.

Sarcofagus, on the other hand, is a site-specific sound sculpture in which a concrete structure, seemingly massive and permanent, becomes a throat – a living, resonating channel – and a sarcophagus in which sound is retained and preserved, creating a tension between what is fleeting and what remains. The combination of the two reflects the tension between life and death, transience and permanence, which are the basis of this work. She was inspired by the work of Alina Szapocznikow, especially her research on hybrid, fragmented bodies. Inside the structure, I hid what I call a “monster” – a hybrid being whose voice fills the space. It is a sound composed of fluids, gypsy-like disturbances and choral structures that resonate in the concrete chamber, reaching a powerful, almost ritualistic climax.

Chimera, photo by Konrad Ciszkowski

NP: On a performative note, I wanted to ask you about Zwodnicze Syreny (eng. Deceptive Mermaids), one of the newer projects you’re working on in the new building of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

ZM: I was invited to Zwodnicze Syreny by Marta Ziółek, with whom I have collaborated several times before on performative works that have a ritual and emancipatory context: Monstera and Nawiedzenia i ekstazy na placu (eng. Visitation and ecstasy in the square). In the installation, I used recordings of seaside soundscapes, and for other scenes I produced hip-hop backing tracks with a simple melody but an elaborate, gypsy-like structure with a high content of high-frequency components and occasional low-pitched sounds to give this bitmejker work some error, also needed narratively in the overall structure of this art.

NP: In many of your works, such as the Polish-Japanese-Ukrainian Re-interpretations presented at the Osaka Festival, you address the theme of the liberation of Ukraine, the country in which you grew up. What were the key themes and goals of the project carried out during the residency, and how can engaged art, including soundscape works, inspire reflection on geopolitical change and the future in a post-colonial and migrant context?

ZM: Yulia Krivich, Taras Gembik and Marta Romankiv were invited to a residency at the Osaka Kansai International Festival, where they worked on projects exploring postcolonial and migration issues. They also invited me to the project to compose a soundscape for the presentation of the exhibition, which aimed to encourage the participants to discuss the future of the region in the context of current geopolitical changes. The curatorial focus of this project has been on creating art that explores the tools artists can use to reflect on a new future in the face of war and postcolonial transformation.

In this context, engaged art becomes a tool that not only educates, but also emotionally engages the audience, inspiring them to rethink their own beliefs and actively participate in the process of change.

NP: Recently, there have been an increasing number of events that create a space to discuss the situation related to migration and war. This is a very emotional and difficult topic that often does not find enough space in everyday conversations.

ZM: For me, a great example of an initiative that actively addresses issues related to the invasion and its consequences for the community is Kyiv’s K41, a key support venue that combines artistic and social activities. Events are held there, with all proceeds going to the front, showing that culture can have a real impact on aid.

In addition, K41 is also a space for education and artistic development, featuring exhibitions, workshops, and classes that foster community ties. I had the honor of performing there several times in its first years of operation, i.e. 2019–2020. This summer I had the opportunity to return there twice – I performed both as Zoi (concert) and Facheroia (DJ set). Each time, I felt how the incredible energy of the place affects the community, not only through music, but especially through collective action and caring.

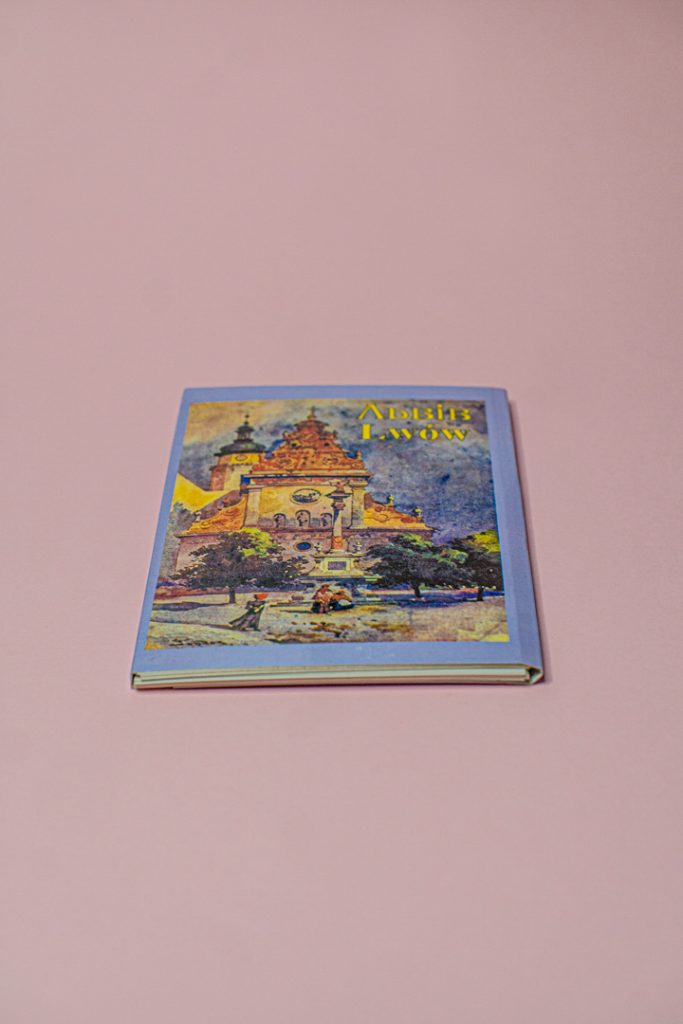

NP: How did growing up in Crimea affect you in terms of music? Do you have specific sound memories associated with this part of your life?

ZM: In music school I liked solfeggio lessons – because you’re in a group, it’s fun. Classical music education, which ran parallel to classes at a tenth-grade unified school, brought me little satisfaction. I grew up in a fairly diverse environment, but I think I was most drawn to doom metal or hardcore by the acrimony among friends. There was also a period of time when I was part of a sludge metal band, playing simple guitar arrangements.

Crimea is a very romantic place. While living there, I often went on overnight camping trips. Of course, we were always accompanied by an acoustic guitar at the campfire 🙂 I have always been interested in connecting with nature, being in wild places. These excursions were accompanied by a rich, natural soundscape. On top of that, there were also various stories and legends, which sound even more mysterious in such wild places. I associate all this with home. Being in the company of a dark and isolated nature, one gains concrete experience. I think I first started revisiting the Crimean audiosphere with my memory after reading the book Notatki z terenu by Marcin Dymiter, who describes the surrounding soundscape in a very characteristic and engaging way. When I lived in Crimea, I didn’t write down all those sounds, but there were reflections and feelings of nostalgia. That’s why, among other things, I began to be interested in the topic of acoustic pollution and acoustics in general, after which I carried out the project Czy to pogłos odwiecznego świata (eng. Is this the reverberation of the eternal world)? (2020) as part of an art scholarship from the City of Warsaw.

Zoi Michailova, photo by Maria Lubicz-Łapińska

https://artmuseum.pl/wydarzenia/zwodnicze-syreny-marta-ziolek ↩