reinterpretation freeforms set

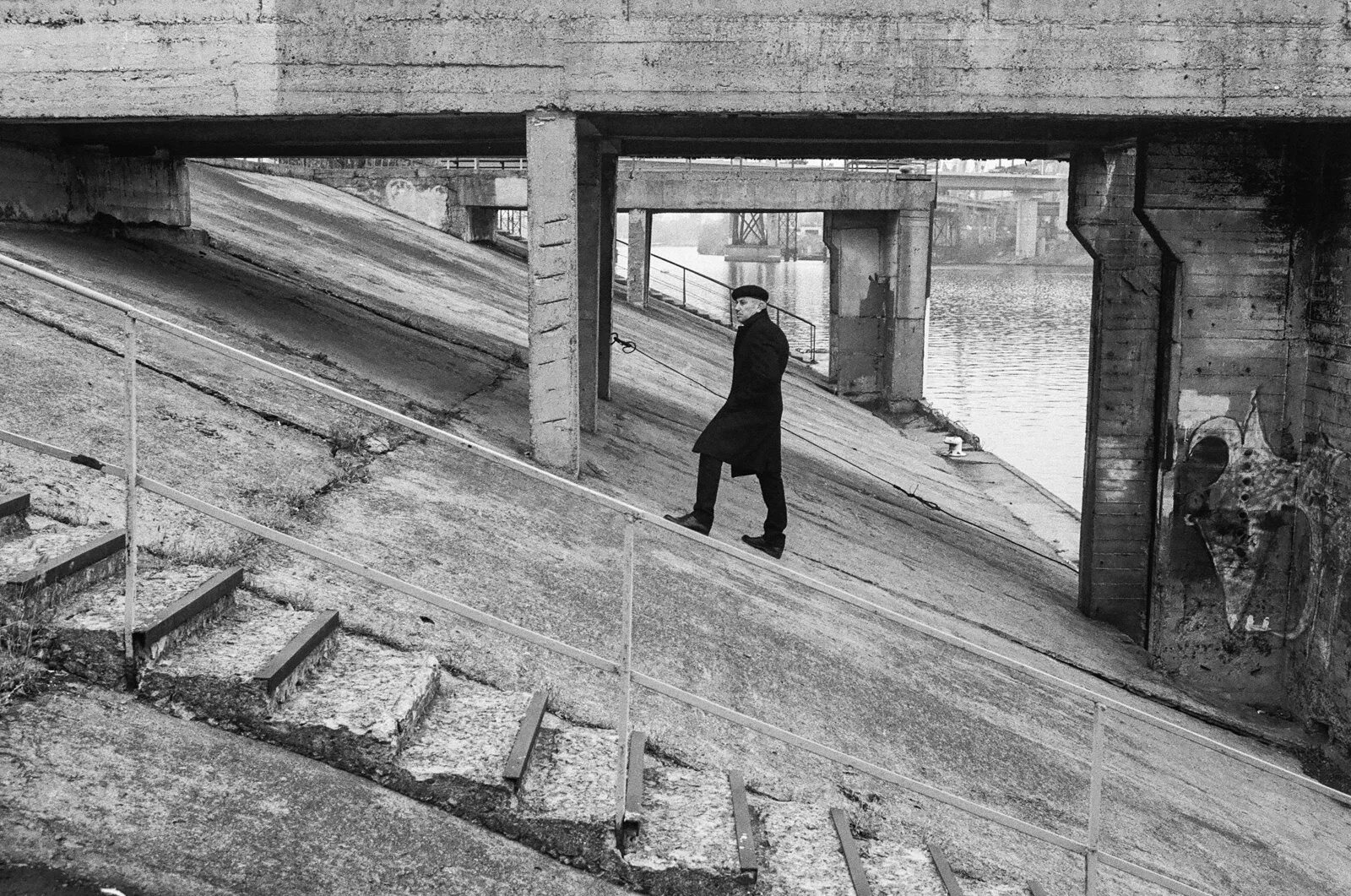

Ihor Tsymbrovskiy: cultural survival

When I first heard of Ihor Tsymbrovsky some ten years ago, he was part of the Ukrainian musical Atlantis, an essential part of the fabled underground scene of the 1990s which flashed brightly before collapsing into an internal exile. Overlooked by the public, disregarded by critics and barely recorded on physical media – this world has only re-emerged into the public eye thanks to the efforts of musical ‘diggers,’ treasure hunters in their parents’ attics unearthing sources of nostalgia amongst millennials for the fabulous times of no-budget masterpieces.

The figure of Ihor Tsymbrovsky is unusual even against the background of this colorful riot of underground heroes. Although professionally fulfilled as an architect, music lovers know him only through one cassette Come, Angel (Koka Records, 1996), an album with extremely unusual vocals.

At the same time, there was a series of club performances — mainly in Poland and Germany. However, by Tsymbrovsky’s own admission, the many attempts to develop creative potential and maintain levels of interest were thwarted by a lack of enthusiasm and a prevailing feeling of inertia.

For a long time, Tsymbrovsky withdrew from public music-making. Notably, his return to activity has again inspired international enthusiasts. In the summer of 2016, Berlin’s Offen Music label released a vinyl record featuring three tracks from the album Come, Angel, an offering to a new generation of listeners. The revival of interest has also been accompanied by recent concert demand and Ihor can again be seen on the stages of music clubs. Together with percussionist Taras Melnychenko, accompanied by a metronome (which the artist treats as a stand-alone instrument, not just a rhythmic framework for a beginner pianist), Tsymbrovsky performs a new program and is reluctant to look back.

Ihor’s first performance in Kyiv in a quarter of a century (!) took place online on 26 November 2020 as part of the Am I Jazz? festival. In the surreal setting of an epidemic, in a closed club, without an audience, the concert was reminiscent of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron in its entire context, when, in the midst of a raging plague, several gentlemen locked themselves in an isolated villa, entertaining each other with playful tales.

As a musician, you have returned to the public space after a period of silence. If you compare the time when you started making music with the current situation, have your intentions and approach to creativity changed?

The approach has obviously changed. In the 1990s, my music was an overture to something bigger than me. Then there was a break, and now I’m back and trying to realize what I wanted to do then. The systems I developed for myself at the time remain. Now they take new forms, because art adapts to the part of the means of expression that is changeable, leaving only what is unchanging and fundamental. I have painting, architecture, poetry; the methods are all different, but the philosophical approaches are similar. In music, I do not set myself any theoretical tasks, nor do I treat it as a field for experimentation. For me, musical creativity is a certain way of cultural survival. What is important to me is this life context: rhythm, melody, the relationship to language, poetry, life space, real, virtual or imagined.

For me, it is very important how the declamation of the piece sounds , how the consonants and vowels dissolve in the singing, and how they combine musically. I conceive of the sound space as a field of my own interpretations, preferences, and priorities. I do not use direct imitation. If I hear a melody, a musical phrase or even an entire musical trend, and it sticks in my memory, I later bring out that element already in my own interpretation as something that was shaped by that particular field. In general, in art, the purpose is contained within the work itself, not outside of it. For me, the motivation has become: “To be is to create a new reality” (a different reality).

Are you now focused only on new material, or can we expect reissues of your archival works such as Sirota, Askold, Intermezzo?

I only have a few recordings of those works as hardly anyone was interested in them at the time. However, I have a number of songs that I wrote twenty or even thirty years ago, and now I play them anew. I wanted to organize the repertoire, for example, ten songs for one album, twelve for another, but at the time it was not recorded and did not survive. Now I have a plan formed for the texts of Vorobyov, Antonych, Semenko, as well as my own and other authors. These works are still in the process of being formed, but I am hoping, with luck, they will be realized.. Folklore has always been among my interests. At the end of the 1990s, in the folk laboratory operating at the Academy, I had the opportunity to listen to material compiled by my friends and began to rework it a bit. I was particularly moved by the song Sirota, which was performed by a lyricist, so I had an idea and started to form a concept album, but it was not realized. Similarly, I worked musically on Apollinaire’s texts in the original — only one piece remains from this. For that, the studio-recorded INTERMEZZO 2000 material remains.

Your performance will take place as part of the Am I Jazz? festival, whose name plays with genre stigma. Is the context in which your music is considered important to you? Do you think of yourself in terms of specific labels, or are you closer to the currently fashionable concept of post-genre?

Post-genre, from my point of view, is a normal term and I see no need to classify my work. My music is the result of diverse musical views, embedded in the way I play. I was heavily influenced by choral works, choral aesthetics, classical music and the 20th century music I grew up on. The influence of, for example, Denys Siczynski or Petr Nishchynsky, as well as Ukrainian melos, from pure ethno-authenticity that has survived to our time, conventionally through mannerism or baroque and romanticism, to contemporary interpretations, is extremely important to me. Until the sixth or seventh grade, I listened to and learned from examples of classical music. Later, I had already heard Western rock music, which at the time was taking over the streets and creating an alternative to the official media. There was no similar Ukrainian music, and what I lacked, I tried to make up for on my own. I call it “street music” because I played as I walked the streets, which created certain associations for me. Now, of course, the circle of interest has changed, but the principle of such spatial, virtual association remains.

Speaking of the festival experience, the specific form of organization of this performance cannot be overlooked. This is the second online performance in this pandemic year. How does it affect you when you play? Do you miss a live, in-person audience?

I find performing in public quite difficult so performing online feels slightly more comfortable. Since everything is recorded anyway, there is always an audience present. Ideally, I would like to write a piece and then observe its performance. I am an architect by training and in terms of my perception, worldview and mindset. I am satisfied with the situation in which I create a design, according to which the building is created and the space is shaped. The finished object can later be evaluated separately and continuously over time. It’s the same with music – I write or record a piece of music, and then I want to listen to it and evaluate it from a different point of view – that of the viewer. Therefore, concert performances are the process of creating music on stage, which should replicate the process of composition and rehearsal as closely as possible. Only then can the maximum effect be achieved. Equally important from this point of view is the continuous work on the material in studio conditions (which I miss). I would record some played themes or single fragments on cassettes in order to think about them later, develop certain motifs and use them compositionally. Now I also save these seeds of composition in an everyday way – on my phone. Later, I go back to them, dive into my inner mainstream and see if they resonate there. Since I started this practice, I’ve stopped listening to other people’s music for fear of losing something important. That’s why it’s curious to me when sometimes someone says I’m similar to a certain performer – and I may have never even heard it.

A renewed interest in your work has already occurred in the Internet era, in which the boundaries of cultural identity are largely blurred. What are digital technologies to you – a visualization tool, a way to shape the environment, a duplicate of reality or something else?

The release of this vinyl became the starting point for me to return to my music career.. It confirmed my feelings that I can still make music – and not just “for the drawer.” Somewhere back in 2011, when I felt the need to make music again, I consciously decided to switch to an electronic piano, since the technology of the hammer mechanism of the keys had already become more accessible. I had previously performed exclusively on an acoustic instrument, and those two poorly organized concerts in the 1990s, when I played an electronic instrument instead of a classical piano, were a disaster for me – they gave nothing to me or the audience. Now the situation is different. Everyone is curious how such a specific sound was achieved in the recording of Come, Angel. It was partly thanks to the acoustic resonance between the vocals and the ESTONIA piano, which I was able to realize live in the studio, without additional interference from the sound engineer, artificial hardware manipulation during recording or mixing, and also thanks to the specific sound of the Soviet electronic instrument, whose tapping keys were picked up by the vocal microphone.

This approach was conscious, and corresponded to my demos. Digital technologies presuppose a different kind of work with sound. The object of this work is precisely to construct, to model the “nature of sound.” Currently, I use the minimum that is available to me for financial and organizational-practical reasons, and which I can operate on my own during performance. This is the simple software built into a Yamaha digital piano. However, in my opinion, at this stage and under the right circumstances, it can also produce an interesting effect – as can the simplicity of the approach with the 1995 recording. At the moment, I put the main emphasis on the musical development of the material, rather than on its sound processing. Full-fledged work on sound requires the use of advanced software, which is in my future plans and will require the realization of creative intentions probably involving like-minded people and related organizational and financial issues.

Do you have the paradoxical impression that unlimited access slows down progress? That we have everything, and we don’t know where to go next?

This illusion stems from the sense of having unlimited resources at one’s disposal, and in this widespread affluence, it has become very fashionable to go to the extreme of individualism – creating one’s own schools, circles, creative circles, sticking dummies. Using off-the-shelf mechanisms is a utilitarian approach, and the information revolution has opened up vast resources for this. It is what allows anyone to make a “creative” product. As a result, we are in danger of living in a simulator – a world of equal-variety, devoid of phenomenon. Who is popular on YouTube today? Who can have five million subscribers? The one who will say something simple and easily understandable to everyone. If you are a freak or incomprehensible to your audience – no one will like you. Everyone is looking for something similar.

If we speak in Umberto Eco-style categories, the information network is flattery – it’s a network of flattery, as people seek and find like-minded people, projecting their popularity. And if you dig deeper, all these characters are very similar, in fact identical. They are the sum total of memes that everyone has long understood.

If we generalize it even further, man today has the ability to process the world more quickly in his own likeness and not perceive, appreciate the diversity, phenomenality or substantiality of phenomena – it’s a world of averaging waste, vanity, self-indulgence and disrespect. It’s a world of kitsch. And only a well-organized social and cultural structure can counterbalance this.

I started making music and painting art while being in a completely opposite world – an ideologized world, a world of information hunger, a world of dosed and distorted information. Creation was a window to freedom for me. My turning precisely to music was somewhat forced, because in the sound space there was no system, there was no Ukrainian music – this is what I call “choice without choice.”

Let’s move on to your formative years as a creative person. For many young people, your songs from the album Come, Angel are important as a manifesto of free, subjective self-affirmation – how much of this is in line with how you entered music-making in the late 1980s? To what extent did the Lviv art community of that time in general have a drive for subversion and experimentation?

Yes, it was a manifesto – for me it was a revolution. In 1987, I was accidentally invited to participate in a concert of contemporary or new Ukrainian songs (I don’t know what to call it) because someone heard my demo tape, which was circulating in certain Lviv circles. Then, during the concert, in the midst of a more or less traditional sound, my performance became a kind of cultural revolution. During my performance, one guy turned off the electricity in the hall, came on stage and announced that you can’t sing Symonenko’s poetry in this way, that it’s a disgrace. Of course, I thought it was some security service, but it turned out that it was a manifestation of the cultural conservatives. He was supported by a few people, but the vast majority were ready for this aesthetic.This was the new generation of Ukrainians.

After half an hour of cultural discussion in the hall, I finished my performance. Very telling in this context is one of the reflections on Emir Kusturica’s film Underground – when people who lived underground for a long time prepared to come to the surface, they did not take into account that the world has changed in their absence, and that their preparations are illusory, and that after coming out their skills will turn out to be lifeless, absurd and theatrical. I am cautious about the word “experiment.” In my philosophical essays, you can see the thesis: to get freedom, you need to get out of the mainstream. An experiment is a choice, and I had no choice. I had a virtual listener that I created for myself. You don’t look for listeners now, when you have to perform at a concert, you have no idea who will find your work. I have created a virtual ideal listener for myself who is the epitome of what you need and how you see the world and work for it all the time – that’s the inner goal. Then comes the fear when that ideal listener is not there, and you have to go out to the real audience. This is the experiment,whether you will become part of the culture of a given environment or it will reject you.

The falsetto’s incompatibility with post-Soviet prejudices about singing, including gender stereotypes, may have played a role in how the average listener perceived your music at the time. Have there been cases of rejection or, on the contrary, admiration and support from people who do not fit into this normativity?

The first remark about my singing was in a note in a Lviv newspaper, which said that I was “the Lviv Farinelli.” Perhaps in this way they wanted to do advertising for me. Well, bad advertising is also advertising – even better. Actually, that’s what I call kitsch – something that gives neither truth nor understanding. It does not focus attention, but only promotes a momentary interest. If you see me as another Farinelli, you won’t be able to connect with my work because you will have a pre-conceived notion in your head

Why am I so vocal? I sang as a dikshant in the Dudaryk boys’ choir. Sometimes I would turn on a Robertino Loretti CD and try to imitate him. Then the voice began to change, and when I started singing in baritone as an adult, I noticed that with falsetto I hit every sound, and I couldn’t with the “normal” baritone. In this way, you can say that I did not let this childish voice disappear completely. I think another part of this was the desire for change, rebellion, and refusal of dogmatic traditions. I was also listening to Western rock records, where the British were using singing techniques that were unheard of in our country.

By the way, one can sense something similar in your recordings: expression or a certain similarity of form. Were you then influenced by the experiments of psychedelics, art-rock? Or, let’s say, performers like Czeslaw Niemen?

When I was about 12 years old, I accidentally (I think I was with my father on a walk in the park) came across a performance by Polish musicians on the open stage of the Green Theater. Passing by, I joined the interested parties who had gathered at the fence of the stands and climbed up trees to see where the music was coming from.

This was the first (and last) time I heard Czeslaw Niemen live. It was original music, sung in their native language, not an English-language cover. Of course, it was not something alien for me, because we listened to Polish radio, but to see and hear Dziwny jest ten świat [Strange Is This World] live – it was amazing. For us, the entire pop scene was based on three chords. Even if there was a solo improvisation later, the main harmony of the song was still the same. Western rock culture struck a completely different chord, and that suited me just fine. After learning about rock standards, I listened to art-rock itself. For example, The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway – this also gave me a boost. One more thing, important for my development – classical music of the 20th century, which reached us through foreign media and over time began to be performed in concerts. An understanding has begun to emerge in the public space that philosophical thinking does not end with Hegel, and academic music does not end with Verdi’s great operas.

We heard that after the release of Come, Angel you had a studio session in Poland and attempted to record new material.

That was Nakonieczny’s idea. I kept looking for people that I could collaborate with musically, but I didn’t want to repeat Come, Angel. From what I understand, he wanted to develop my existing format, but I was already starting to form different ideas and approaches. It was at the experimental studio of Polish Radio, where Tadek [Tadeusz Sudnik] worked.

There was a grand piano standing in a large empty room for a symphony orchestra. It was cold, and we were recording at night straight after the concert. I simply couldn’t cope, either mentally or physically. You can’t step into the same river twice. A song from a 1998 concert in Gorzów still survives. In those years I had several tours in Poland and each tour was usually seven or eight concerts. Once or twice I rode with Svetlana Nianio.

The organizers wanted to record one or two songs, we were supposed to agree in advance. The concert was held in winter, so it was cold on the stage in the club. My hands were freezing, I started warming up on the piano and played my “company” fast passage to one composition. The sound engineer wanted to record it beforehand, perhaps also because someone from the audience also responded positively to this passage, but I was not sure about this choice, because I am not a professional pianist, and at that time the main emphasis was on the original vocal technique. During the concert I chose another composition to record, with interesting vocalizations, which ended up in a compilation titled N/T. Together with Nesterov and Yaremchuk, I had a joint concert in Lviv, I think as part of the “Alternatywa” festival, just like the concert Come, Angel in the Dominican Church organized by Ruslan Koshev in 1996, just after the release of a cassette with the same title in the Warsaw music publishing house KOKA.

Tell us, please, about Psalms and Hymns.

I have chosen several poets whose poems I sing, including Bohdan-Ihor Antonych. When I started playing again, his words prompted me to write a series of compositions based on his poems. I have recorded twenty-three songs with Antonych, although the last composition is not yet completely worked out. I also have eleven works on Vorobirov’s poems, almost completed. Of course, the main material is based on Semenko’s poetics, my own poetry, and a few works by Tyczyna, and Symonenko. For music, I chose works by poets who are not widely read in our country. So I’m opening up another point of view on their work. As for Antonych, it is not “Antonych grows and the grass grows.” Poetically, it is different for me than how they portray it in the mainstream. Semenko is also different for me – his pathos, which is mostly emphasized, is only an attention-getting mannerism, not a poetic sensibility. What Semenko wrote in the roughly two decades before and after World War I, I consider to be the best of Ukrainian poetry of the 20th century.

Do you feel you are continuing a tradition, perhaps an avant-garde one?

I try not to limit myself with categories or definitions when thinking about new techniques or ways of doing things. My thought process is that the thing itself is important, and reproduction or imitation is a weakened form of it. How do I approach this? Well, if we understand this as a relationship between the ‘sign’ and the ‘signifier’, then the sign is a permanent form, but there is often fluidity, change and play between the sign and signifier.

The title Psalms and Hymns refers, so to speak, to a sacred theme.

Yes, because this theme appears in Antonych’s work. He was deeply interested in cosmology and well versed in religion t, and had a university education in philosophy and theology as well as philology. Vladimir Ivkovich experienced some disappointment when the text for Come, Angel was translated into English. Ivkovich treated this composition in its own specific sacrality (perhaps sacredness in a broader sense), and the translation has an erotic connotation. A magnificent translation of this text in a different, but also sacred way, was done by Lev Hrytsuk (R.I.P.). For me, this is where the interesting issue of the linguistic aspect in the performance or sound of the composition lies.

It’s interesting, does your current performance of your own lyrics in English translation have conceptual overtones and is it aimed at a global audience?

For me, it’s a conscious act. I used to sing in Ukrainian at concerts in Poland or Germany, and the main emphasis was on the melodiousness of the combination of language and music. And this satisfied both the listener and the performer, regardless of whether the content was understandable. The work presented the listener with a new form of linguistic phonetics that went beyond existing ethnic stereotypes.. It was a kind of mission. In those days, there were still attempts to sing in the languages I spoke (mostly phonetically) – that’s Polish and French, which had a good basis, because they were languages that were part of my identity, and included, for example, Apollinaire’s poems. With English, it’s a different story. Being brought up on the phonetics of English-language music, I composed Ukrainian lyrics to it, which made sense – not to imitate what you listen to. Now the performance in English has opened up to me the sense of new sounds of English translations of Ukrainian texts, namely: new intonation, some compositional changes in the songs under the influence of English phonetics, and at the same time the poetry, in its essence, in its original connotation, remains Ukrainian and is devoid of the banality of English-language imitation. Now it is a kind of discovery for me. It’s such a globalized mission and vision, which also gives a certain common denominator – its own internal virtual stage – a certain idealized artificiality, an unnaturalness that is measured by the truthfulness and naturalness that only falsetto gave before – it’s like watching the process from the side.

In new interviews, you have said that you yourself are leaning toward the mainstream, “coming out of the underground.” What does the mainstream mean to you?

Tori Amos or Björk. They initially existed outside of the mainstream but managed to bring their uniqueness and authenticity into the mainstream. |I am interested in these original ways of working.. In the mid-1990s (already after the release of Come, Angel). I was tasked with recording the musical accompaniment to a fashion show. It was an interesting time then.

Björk was working with techno in London at the time, and that got me interested. I superimposed my compositions on the instrumental version of Army of Me and one of Massive Attack’s (almost) instrumental compositions in the analog studio (in my opinion, it sounded quite organic) – these were interesting mixes that served their function in fashion and then they disappeared. Other ideas, such as the later INTERMEZZO 2000, were never developed any further. This actually contributed to stopping my musical activity for about eight to ten years.

I would like to end our interview with a conceptual question. Earlier you said that in our country the art market has not been formed. Recently, artists in particular have placed a lot of hope in the Ukrainian Cultural Fund, the Ukrainian Institute, etc. In your opinion, can kitsch, lack of taste, cultural emptiness be overcome institutionally? Is this an existential question that is not solved by institutions?

Now, this is probably the main possibility of existence in the non-market relationships we are in. For this to be possible, it is necessary to have a good expert environment and orientation, to be able to evaluate and see the value of the material. In this aspect, it is important to understand Kitsch as a thing that sees its purpose beyond the work. That is, if we see the work in advance as insufficient in itself, and as something that can produce a result outside of itself directly, the goal will never be achieved.. As for my business, I have projects ready to be implemented, and the main question is about organization and management.

Translation: Maria Kozan