Digital analog remote control

UKRAiNATV: the future starts here

They mix art, activism and technology to create a dialogue across Europe. Meet the internet TV project UKRAiNATV, featured at Unsound 2023

The world of music is in perpetual motion, always seeking new frontiers and challenging the established norms. In this ever-evolving soundscape, the Unsound Festival in Kraków has carved its niche as a bastion of experimental music and avant-garde exploration. As the festival gears up for its 2023 edition, it promises a unique blend of sonic innovation, critical discourse, and a push for diversity and inclusion.

I scan through the lineup of the festival, and from the sea of famous and emerging experimental and underground artists, I spot the name of UKRAiNATV, a local collective who had earned the victory of Unsound’s open call.

While the festival is well-known among experimental music connoisseurs in the West, there’s a glaring lack of insight into the thriving Central and Eastern European music scene, where Unsound calls home. In a bid to pierce through the Western echo chamber that often obscures the neighboring Eastern musical landscape, I decide to spotlight the internet TV project UKRAiNATV. Their mission? To empower an eclectic ensemble of boundary-pushers among refugees, expats, migrants, creatives often stifled by state control and lack of possibilities, regardless of their nationality or culture.

Promote Ukrainian culture

Without moving much far away, the collective UKRAiNATV operates directly in the very city of Kraków since a year and a half. Their funding situation is also precarious, they arrange things as they can, while also launching a charity campaign for Ukraine. Behind their Dadaistic approach (much in tone with this year’s Unsound theme) lie concrete aims and practical deeds in social and creative terms, aiming at developing those decentralized points, that Mariana Berezova argues for, right in the middle ground between Ukraine and Western Europe. For Unsound, they will perform on October 6 in a stream art session from Kraków’s historic Jewish quarter.

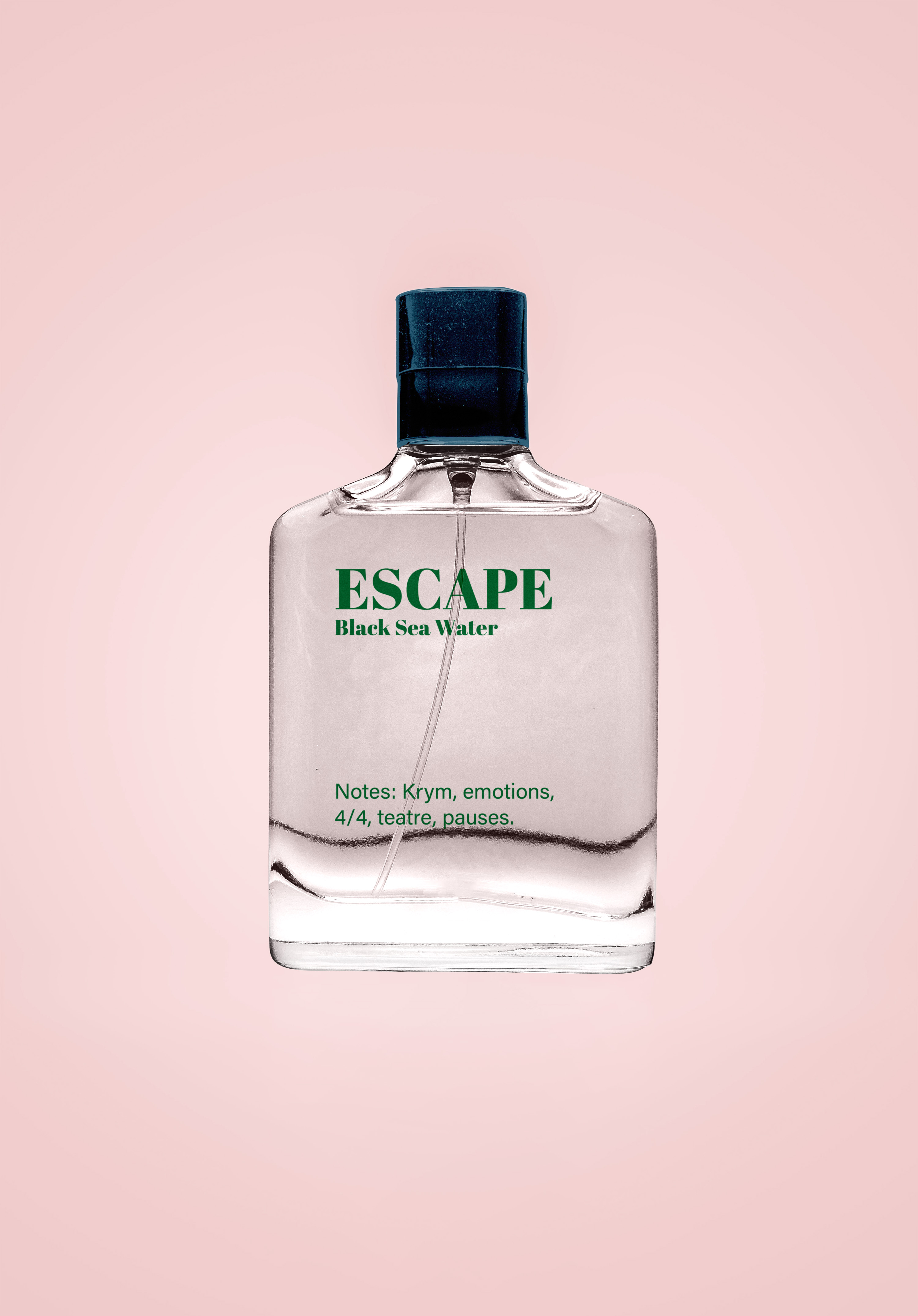

Operating under the STREAMART collective, UKRAiNATV amalgamates art, activism, and technology. Live-streaming from the #StreamArtStudio, it establishes a haven for war-displaced refugees and emergent creatives from the region, evolving into a versatile platform for underrepresented youthful perspectives often overlooked in conventional media. Employing traditional and experimental technologies in the attempt to blur the distinctions between the tangible and the digital, it fosters a “glocal” environment of diversity. StreamArtStudio, functioning as a lab, and UKRAiNATV, a transhuman collective, emerged as experimental internet television in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Their content encompasses culture, art, and human experiences, blending in performances that showcase innovative ideas and artistic expressions and uniting technological and artistic perspectives in their research efforts.

Since March 2022, they have curated over 60 hybrid, live-streamed events, known as #EFIRS. These events feature contributions from diverse artists, activists, DJs, writers, journalists, and performers, spanning Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, Italy, and beyond. UKRAiNATV and StreamArtStudio serve as a research hub where people, technologies, machines, cables, and data converge to create parallel realities. This hybrid fusion is central to their mission, which is to explore new frontiers through streaming. They host weekly live streams in its fourth season, airing every Thursday at 6 PM on multiple platforms.

Ksenia Mirgorodska: We use several platforms at once also because we never know where we will be blocked. We are blocked by platforms from time to time.

Giada Dalla Bontà: For what specific reason have you been blocked? Is it related to your DJ sets streaming and copyright protection? Or is it more about the content itself?

KM: You never really know. Sometimes, bans are due to our music, sometimes for publishing content that does not align with YouTube’s standards. For instance, our exploration of performative uses of Shibari was banned, although it wasn’t explicit nudity: it was just a Shibari practice with ropes.

Rom Dziadkiewicz: It is unpredictable, although bans often relate to sensitive subjects, occasionally delving into social-political contexts.

Gleb Dovzhuk: Our interviews are grounded in these social-political contexts. We showcase prerecorded or live sets from invited musicians and producers, along with interviews featuring artists primarily from Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, Italy, Kurdistan and elsewhere. While Ukraine remains our focus, we stand with minorities and those facing imperialistic challenges in their lives and countries.

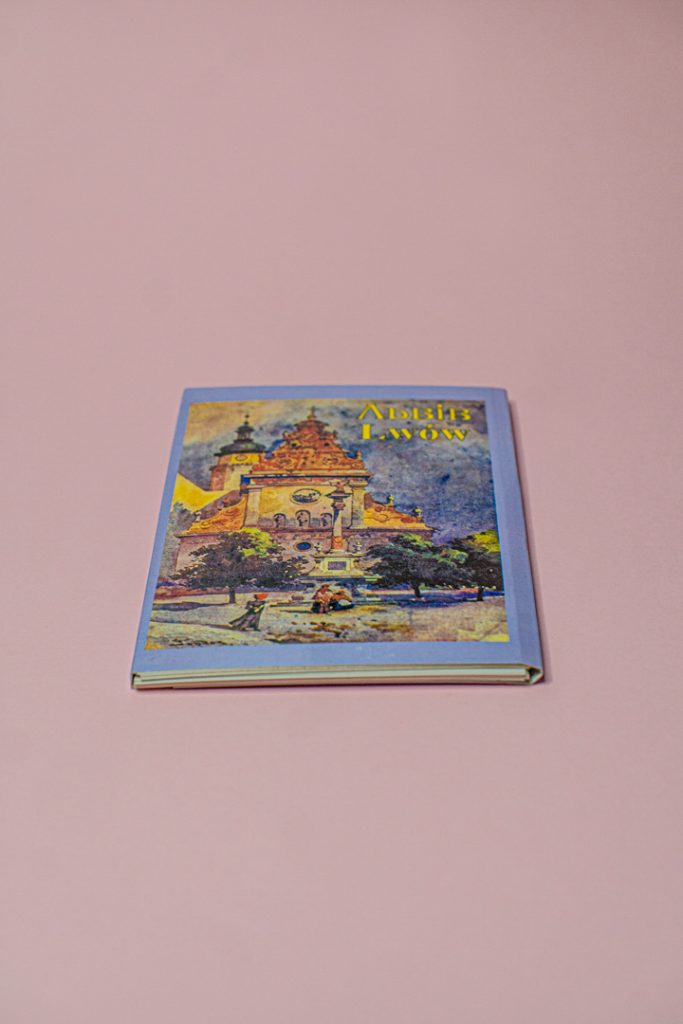

KM: At its core, our mission is to provide a platform for these people and anyone else to showcase their work. This is why we’re also a research project trying to develop new technologies, and blending elements that are still thought incompatible. This is our primary objective. It’s crucial to note that we adopted the name UKRAiNATV because we emerged during the full-scale war. Our primary goal is to promote Ukrainian culture. Over time, we’ve collaborated with institutions like INC [The Institute of Network Cultures] in Amsterdam and worked closely with NTNU Trondheim [Norwegian University of Science and Technology] in Norway. What I’ve personally discovered is that many people in the West, even at conferences, have limited knowledge about Ukraine and its neighboring countries like Belarus. We’re also working to connect Belarus to our mission because our region often gets overlooked, but our ultimate focus remains on showcasing Ukrainian culture. In fact, we’re going there in two weeks to open a collaborative studio in Kyiv, aiming to build a bridge between Ukrainian and Western cultures.

Shaping a new future

GDB: From what I gather, your approach is not only rooted in your local context but also aims to provide a space for people in similar situations worldwide. This decentralized, or as you call it, “glocal” approach, could also be seen as loose translocal communities: interconnected globally while remaining firmly grounded in the local scene as well.

KM: Absolutely, building a community around us is a central goal. Kraków, where we’re based, serves as a perfect hub, bridging connections between Ukraine, Belarus, and the western parts of Europe. It’s an ideal location for our mission.

RD: It’s an ongoing learning process, given the complex historical issues in our region involving Ukrainians, Belarusians, and others. We’re faced with the challenge of how to come together and shape a new future in the midst of the transition from neoliberalism to what I refer to as the new imperial period, both in a geopolitical global context and within the digital corporate landscape. Recently, we participated in a conference in Sarajevo, which was a poignant encounter with people who are still dealing with the post-war conditions. They too face the question of how to foster unity. This issue, while local, also has regional and global dimensions. Our presence at such conferences serves also as a call for partners and a plea for dialogue across Europe.

GDB: The diverse and, for me, partially unfamiliar languages I met when I first watched one of your Efirs, created a soundscape of “multicentrism”, where communities strive to connect amidst the differences and similarities within the region. Simply listening to unknown languages is a valuable cognitive exercise, socially and sonically. How do you handle language on your platform?

KM: To give you an example, Roman is from Poland, I’m from Belarus, and Sofia and Gleb are from Ukraine. We use at least three languages in our studio and in almost all our #Efirs, we aim for at least a bilingual approach, incorporating languages like Polish, English, Ukrainian, and now Belarusian. We recognize that not everyone speaks English, so we strive to be flexible, and speaking our native languages is both natural for us and helpful in our multiple attempts to organize donation initiatives and charity events.

GDB: You mentioned that the project started during the war. Can you share more about how it began? Was it born as an already consolidated and structured project or did it emerge in response to the crisis, evolving as events unfolded and people got involved? And how did you transition from the war context to streaming art? Kraków played a crucial role as one of the first cities to welcome refugees.

RD: The studio quickly became a vital hub for people, including refugees, arriving in Kraków during the early days of the war. It served as a gathering point for those seeking shelter and connections. It was a 24/7 space where people came to meet, share information, and seek solace. We were gathering information both at the border and in the railway station, where some of our team was on-site, while others were in the studio. We recorded interviews and meetings, capturing a truly significant and testimonial moment. Originally, the studio was meant for research and streaming art, but the urgency of the situation shifted our focus. We adapted, learning day by day how to be more effective. Now, we have a stable program and team, going beyond technology to engage in social, political, and artistic activities. Our team doesn’t have a stable budget for proper full-time jobs. We’re doing our best with the limited resources we have, but it’s very basic. Poland follows a quite monolithic vision of the ‘one nation, one state,’ and somehow is focused on Poles only, but on the other hand we are in a very multicultural city now, so we face some form of skepticism (someone said that there are aliens in this studio), and we do not receive big support from the city council although all in all there is not hate towards us. To sustain our work, we rely mostly on support from international networks. It’s exciting, but it also presents its challenges.

GDB: It seems that sound plays a unique role in your sessions, almost like glue holding everything together. How do you view music’s role in your work, and does it differ from session to session?

GD: Music varies in its role. It can be the glue as the main act, but it’s never just background noise. Sometimes it’s the focus, like when we perform live. We use a mix of instruments, including drum machines, oscillators, guitars, and vocals. Music is essential, and everyone contributes in their own way. We’ve shifted from DJ sets to focus more on music production, although we still occasionally have DJs in our shows. Kraków, being a crossroads for artists touring or travelling from Ukraine to the West, allows us to collaborate with musicians passing through. We record live sets and interviews, giving them a platform to share their stories. Music is a tool, a soul, and simply the cherry on top of this tasty cake that is UKRAiNATV.

RD: Our sessions are quite diverse, but music is always a medium that brings us together, a language beyond words. It’s a way to exchange energy and ideas. We also serve as an archive while inviting other artists and musicians to share their work. It’s about the freedom of creation and a space for experimental electronic music. Sound is thus a space for collaboration, like our projects with the experimental feminist art performance band Chicks on Speed. We’re always open to new creative partnerships.

GDB: I’ve come across a transmission featuring music performances by a group, only to later discover that they were miming playback. The actual performers, which I believe to be in fact Chicks on Speed, didn’t seem to be physically in the studio, which completely shifted my perspective on space and performativity. Can you explain what that was about?

RD: It’s worth mentioning that this was part of a larger conference, the Society for Artistic Research, where artistic research was a key theme.

KM: Yes, we were at SAR in Trondheim and we met Alex, who proposed collaborating with Chicks on Speed. What we did was create visual performances during some of their concert shows. We streamed these visuals on a green screen while they performed live, and we also recorded the visuals in our studio.

GD: »It was like having a mini studio on the stage. We sent our signal with a green screen back to the studio as one stream, which was connected to the band’s program. We watched their concert while performing with the visuals received by Rom. The final output combined these two different locations, adding real-time visuals to the mix.

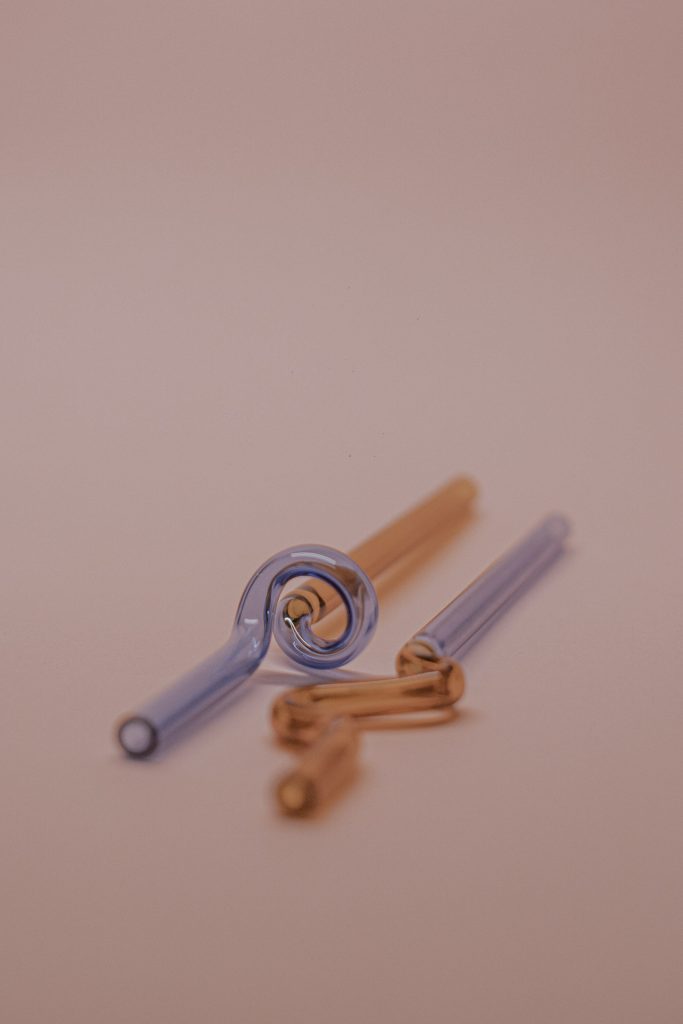

Anna Solecka: We were blending two different countries together. An essential aspect of this collaboration was Chicks on Speed’s focus on feminist empowerment, shifting away from the male gaze. We each worked with specific elements like pole dance, ropes, and silks, with a clear and focused intent. This aspect was a significant outcome of our collaboration.

RD: I like to call it inclusive feminism. We come from a background of post-queer culture, so it’s a meeting and mixing of various traditions and perspectives, which is very important.

GDB: Your sound sessions combine performativity and processuality, creating a post-internet aesthetic where diverse elements coexist, often with a very corporeal presence. The theme of suspension, both literal and virtual, is prominent in your frequent use of ropes and silks: Shibari is traditionally about constraint, but here, it transmits liberation from constraints through movement and sound.

Sofia Reznichenko: I’ve been working with shibari and ropes for the past two years. We’re exploring how ropes can be performative, incorporating acrobatic elements. The creations with ropes hang in the studio often, offering us a canvas for experimentation. Many of our recordings are inspired by these installations.

RD: It’s about blending gravity, movement, and the fusion of physical presence with avatars and 3D elements. This aspect involves multi-layered installations, and it carries several metaphorical aspects.

GDB: It’s fascinating to think of a person moving through this net of Shibari ropes as if on a web of cables and networks.

AS: Exactly. In the introduction of our #Efir, Sofia’s singing captured the essence of what we do here, mentioning in fact cables, ropes, and the network. The lyrics naturally emerged, reflecting our reality in a subtle yet melodious manner. I would recommend giving it a listen.

War and music

So, Sofia, you essentially sung an improvised manifesto song! Circling back to my question about the role of music and sound, how would you describe the evolution of music, particularly in the context of the war? Have you noticed any shifts in your perception, not just in music but also in performance art, particularly regarding sound?

Gleb Dovzhuk: »My perspective has transformed significantly. I have finally rejected the notion that music is apolitical. Personally, music has evolved into a powerful tool for not only conveying emotions but also sharing ideas and narratives. For instance, I occasionally perform live jams while reading letters penned by my grandfather, who goes to the frontline at least once per month to give supplies. He describes extensively about his surroundings – the changing of the environment, the cities and villages, often destroyed – or about his fear of the soldiers. Music, to me, is something much, much more meaningful than before. It transcends mere propaganda; it’s a unique vehicle for storytelling and conveying emotions, even if they are not yours. It’s a profound change for me.«

Rom Dziadkiewicz: Our project combines visual art performance and experimental music at its core, drawing from a rich tradition. We’re inspired by Warsaw’s experimental music studios from the 1950s to the 1990s, akin to Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne. We also take cues from Orson Welles’ radio work and 1990s grunge musicians who experimented with early internet streaming. Additionally, we’re influenced by the Institute of Network Culture and the ongoing quest for a decentralized internet, a tradition that dates to the late 1980s and 1990s.

Your involvement in the Unsound program promises performative lectures, tea ceremonies, and VR and AI elements, among other collaborative acts with partners in Kyiv, Amsterdam, and Vancouver. These dreamlike, immersive experiences aim to awaken a glocal and transhuman sense of community under the banner of #HOPECORE. Can you shed light on this term and the concept behind your participation in Unsound?

RD: What we refer to as ‘hopecore,’ while it may seem like a series of psychedelic acts, serves a deeper purpose. It’s a form of therapy at times, a response to stress, anxiety and the lingering fear of a war getting closer. Our special Efir for Unsound will likely span several hours and feature distinct chapters. The atmosphere may be less wild than usual; instead, it will be more reflective and dream-oriented, encouraging a more introspective and perhaps relaxing vibe. Our day program kicks off at around 4 PM, making it more of a tea-time event with carpets and pillows for lying down or even sleeping, rather than an all-night dance party. We aim to keep it open and flexible, with the possibility of collaborative activities such as workshops or singing with the audience who joins us.

GDB: Does this mean that the streaming will still be accessible to everyone as usual, but those attending the festival can also drop by and take part?

RD Absolutely, the event is open to everyone, not just festival goers, and it’s free. Feel free to come and join us.

You can follow their streaming for Unsound in their website, on Twitch, Facebook or Youtube, or visit them in Kazimierz, Kraków.

You can support UKRAiNATV here.

Translation: Andreo Mielczarek. Text originally published at our partner „Seismograf” page, there is also Danish version available.