Voices and Institutions: Insights into the Concert “Artefacts of Voice” in Kyiv

I set foot in the National Philharmonic of Ukraine slightly late. Quickly led through the philharmonic’s corridors, I slip into the Lysenko Hall just in time to catch at least part of the concert introduction delivered by Oleksandr Chornyi. Phew, I made it! It is Monday, October 21, 2024, and here I am at the Artefacts of Voice (артефакти голосу) concert, performed by the Kyiv-based Ensemble 24 and soprano Viktoriia Vitrenko.

The Venue

The National Philharmonic’s building in Kyiv originated as a sort of “gentlemen’s club” which, in the early 1880s, belonged to the Merchants’ Assembly. It began to operate as a concert space thanks to the efforts of composer Mykola Lysenko. After the Bolsheviks came to power, the building served various purposes before it ultimately became the Lysenko Philharmonic in 1962. Located in the very heart of Kyiv, at the end of the city’s central artery, Khreshchatyk (Хрещатик), on the fringes of Khreshchatyk Park (Хрещатий парк), it is just a few steps from Independence Square, also known as Maidan, where the fierce clashes of the Revolution of Dignity (2013) took place.

For over two years, the Philharmonic has served as space for an increasing presence of Ukrainian contemporary music. As Iuliia Bentia writes:

At the beginning of the full-scale war, this [that institutional programming can be done differently – AM] was proven at the National Philharmonic of Ukraine, whose repertoire – despite the difficulties of long-term planning – has changed dramatically. The refusal of foreign soloists to give concerts in the city, which is subject to regular rocket attacks, has given many Ukrainian artists a chance to perform on the country’s main musical stages. Moreover, the deletion of all Russian composers without exception from the program as part of a deliberate “quarantine” has shaken the foundations of the Philharmonic’s rather conservative repertoire policy. It opened the way to the prestigious stage of the Mykola Lysenko Column Hall to fresh and bold programs featuring Ukrainian music. At many concerts, Western European classics resounded alongside new symphonic works by native composers, written after the start of the great war 1.

Nowadays, Kharkiv’s musical life takes place quite literally underground. After the concert, while speaking with Mariam Verdiyan, a member of the ensemble, and Liza Sirenko, a co-founder of the site “The Claquers,” I learn that the balcony of the Lysenko Hall at the National Philharmonic of Ukraine has basically been closed off. And, of course, concerts are suspended if an air-raid alarm sounds during the performance. However, they are sometimes continued in the Philharmonic’s shelter. Three days after the concert I attended, the institution’s music director, Nataliia Stets, told me about such an underground continuation of Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, interpreted by Vitrenko. I must admit that I began to ponder the dilemmas of programming concerts for ensembles small enough to fit in a shelter…

On that Monday, thankfully, the evening in Kyiv was a calm one.

The People

Ensemble 24 is a recent initiative, a group that formed in 2024. At its roots lies the Octopus Society, led by Chornyi, which operates at the National Academy of Music of Ukraine in Kyiv – and it is from the Society’s activities (concerts, workshops, meetings, masterclasses) that the ensemble arose 2. The concert I attend is only their second official performance after their September event (which took part in the same institution), dedicated to animalistic inspirations in contemporary music. During that earlier concert, the ensemble consisted of a thirteen-member lineup, featuring works by Jérôme Combier, Alexey Shmurak, Clara Iannotta, Benjamin Scheuer, Panayiotis Kokoras, and Carola Bauckholt3. This time around, the instrumentalists – Tymish Melnyk on piano, Serhii Tarnawski on guitar, Nazarii Stets on double bass, and Yevhen Ulianov on percussion – perform alongside soloist Viktoriia Vitrenko, who served as the common thread weaving the performances together. Overseeing the electronics is Alla Zagaykevych, the very initiator of Ukraine’s first studio of electroacoustic music.

Ensemble 24

Vitrenko is not only a singer, but also a conductor and curator. Active primarily in Germany, she is the co-creator of several interesting musical projects, such as InterAKT, exploring performance, transmediality, and new media. An example of her willingness to delve into the dynamics of performativity in contemporary artistic practice (but also, among other things, the tradition of instrumental theatre), is her staged solo concert Limbo (a recording of which has been released by the independent label Kyiv Dispatch), dedicated to Maria Kalesnikava. Limbo is a voice of dissent against the actions of the Russian and Belarusian regimes, through her performance (in a poignant costume) of works by, amongst others, Zagaykevych, Agata Zubel, and Maxim Shalygin.

Before we get back to the titular concert, I want to mention Anna Arkushyna, the composer of the concert’s opening piece. A deeply compelling, versatile artist, she braves the spheres of (near-academic) contemporary music, and its relation with electronic music or sound art. She is currently based at the University of Music and Performing Arts, Graz. Just recently Tomasz Szczepaniak performed her Énouement (percussion and electronics) in 2024, while Kwartludium would at various occasions play her 2015 piece The Song of Future Human (for Cl/Bass Cl, Pn, Vn, Percussion). In her artistic explorations, Arkushyna readily turns to acousmatics – the note “acousmatic music” accompanies a substantial group of her compositions. …au ciel enflammée, which opens the concert at FNU, was created as a reflection of her residency at IRCAM.

Photo by Viktoriia Holovchenko

The Concert

At the beginning, the audience is surrounded by a system of eight speakers. Vitrenko engages in a vocal dialogue with them. I am inside an invisible acoustic shape, whose structure is constantly changing.

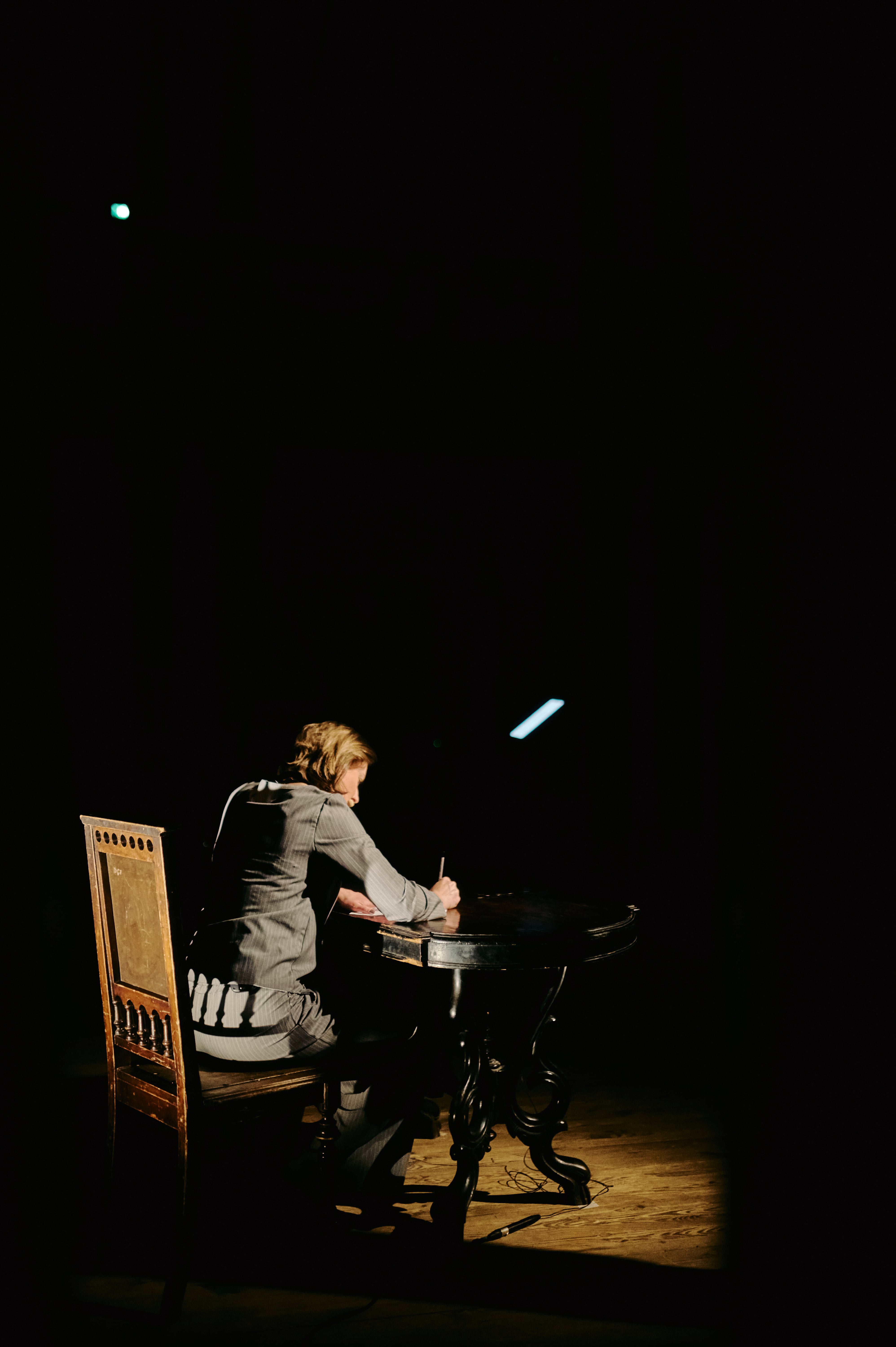

Compared to last year’s premiere performance (available online), Vitrenko is decidedly more subdued. Of course, she still expressively explores the sound-poetic-ish layer of the text, based on the works of Lesya Ukrainka – gradually moving from sounds and phonemes toward language, making the French translation a material for expanded vocalism. However, she operates more sparingly with gestures. The conclusion has a distinctly theatrical-dramatic dimension – Vitrenko sits behind an amplified desk, and I begin to hear (perhaps due to the power of suggestion) the sound of paper in the layer of electronics.

Viktoriia Vitrenko, photo by Viktoriia Holovchenko

This version definitely speaks to me – perhaps even more in this performatively low-key expression. I find it easier to direct my attention on the rustlings, murmurs, and hisses of the electronic layers. Arkushyna mentioned in interviews that her intention was for the electronics to be partially activated by voice, so that they find their own realisation in live performance as well. The spaciousness of the surrounding sounds is astounding, with the movement between channels and speakers setting a dynamic sound space into motion. Zagaykevych might play a part in this, with her experience in spatial sound engineering for this type of composition.

Vitrenko is joined by double bassist Nazarii Stets after Arkushyna’s piece concludes. The two interpret First Leaves (2021), a work by Daniel D’Adamo, an Argentinian composer also associated with IRCAM. This five-part composition is based on excerpts from Goethe’s Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären (in various languages). The duo performs the piece in a fascinating way, full of vocal leaps, galloping double bass, a variety of sound effects, and extended performance techniques, contrasting dynamic changes, as well as exploring the relationship between the two performers, and the texture of the composition itself. Vitrenko involves her whole body in the performance, even removing her shoes before the third part to lower herself more confidently, grounded on her feet during transitions between vocal registers and various vocal techniques.

Nazarii Stets, Viktoriia Vitrenko, photo by Viktoriia Holovchenko

The third piece is a duet of the singer with Tymish Melnyk, another of the ensemble’s soloists. They perform Sechs Grabschriften (2017–2019) for mezzo-soprano and piano by Stefano Gervasoni (student of Luigi Nono, based in Paris). Another multi-part piece, this is the only part of the concert that feels a bit lengthy to me, although the dynamic beginning of the second part has my attention.

Tymish Melnyk, Viktoriia Vitrenko, photo by Viktoriia Holovchenko

Next up in the program is what can be called the beginning of the percussive finale of the concert – Musica Impura for soprano, guitar, and percussion by Mathias Spahlinger (1983). Vitrenko is joined on-stage by Sergey Tarnavsky and Yevhen Ulianov, each of them with their percussion instruments. A Kagel-Cage-like logic of sound event sprinkled with instrumental theatre hangs over the whole affair. Voice and guitar (and a whole lot of dampening!) also function here as elements of the percussive whole. For me – sounds great. Spahlinger wrote that his piece is a musical response to Pablo Neruda’s idea of “poésie impure”, and that the inability to (fully) translate poetry to the language of musical composition, has key importance for him. Knowing this context ties this piece well to the themes raised by Arkushyna’s opening composition.

Sergey Tarnavsky, Yevhen Ulianov, Viktoriia Vitrenko, photo by Viktoriia Holovchenko

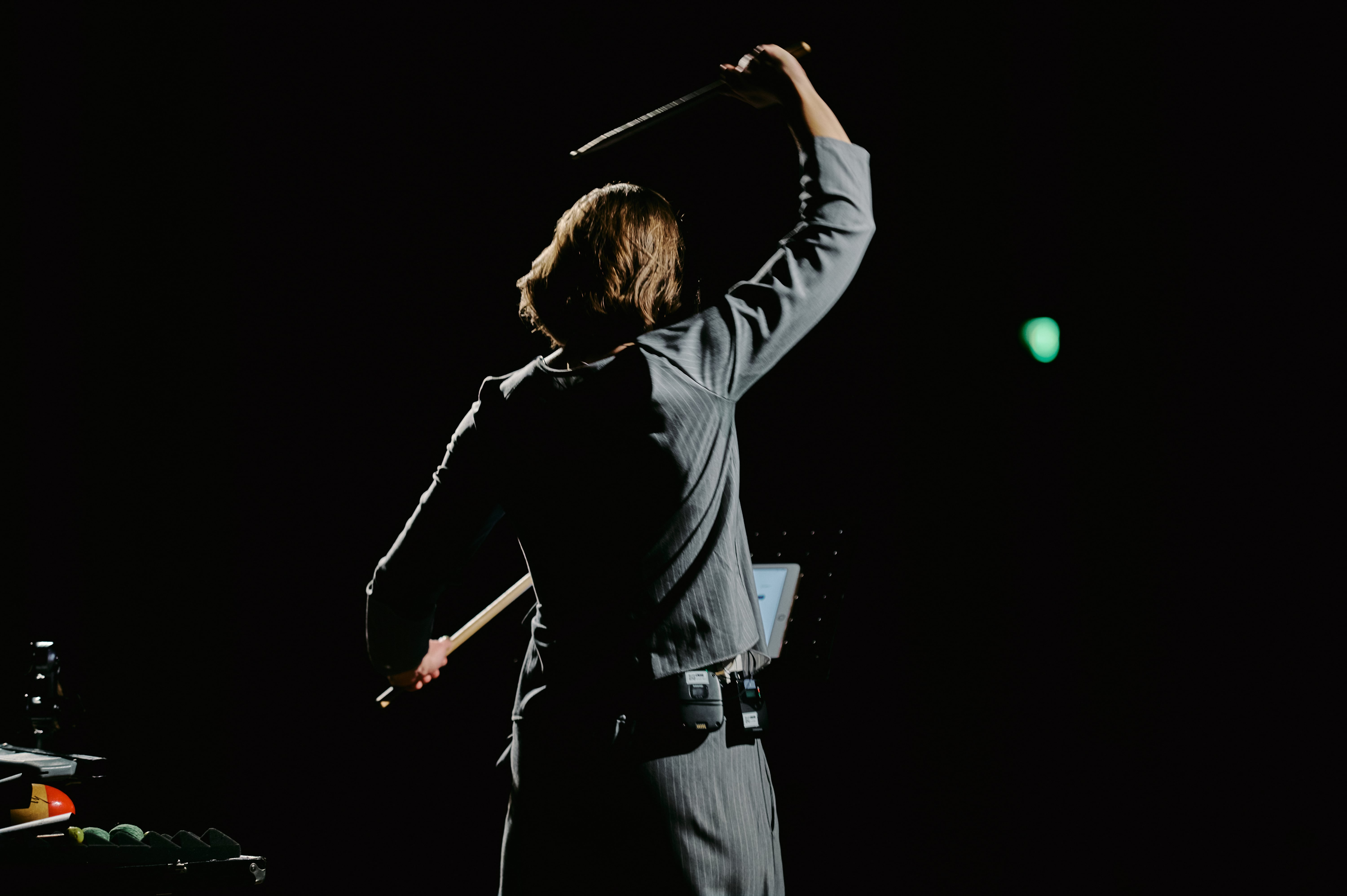

For the final piece, Ulianov switches instruments to a more “rock drum set” type of percussion, and Vitrenko grabs a pair of drumsticks as well. In this duet they perform Sara Glojnarić’s Artefacts 2 for soprano, drum-set and tape 4. The composition explores the history of popular music (through the usage of a whole series of hit songs’ drum intros), in a convention touching on New Discipline aesthetics. Vitrenko and Ulianov’s interpretation underscores the choreographic aspect of Glojnarić’s piece – the percussive sticks take part in gestures and arrangements, bringing to mind the triumphant moments (of a kind of suspension) at stadium rock concerts. Comparing this to, for example, Sarah Maria Sun and Dirk Rothbrus’s interpretation, the choreographic aspect has definitely been accentuated. This is not the only thing that sounds different in comparison to other renderings of the piece – like the electronics, which seem to sound “fuller” in Lysenko Hall, as if the entire realisation was oriented towards bringing its sonic depth to the foreground (again: is this Zagaykevych’s keen ear and skillful hand?). All in all, an excellent and effective crowning of an intense concert.

Viktoriia Vitrenko, photo by Viktoriia Holovchenko

Eugene Ulyanov, photo by Viktoriia Holovchenko

In lieu of a Conclusion – Institutions and Their Activities

So, how did I find myself at a concert at the National Philharmonic of Ukraine? I was sent to Kyiv with a group of Polish journalists for a so-called study visit by the Mieroszewski Institute and the Ukrainian Institute (the equivalent of Polish IAM), and, upon arrival, I was invited to the concert by its organisers. Why would I mention this here? When I was finishing up writing, I asked someone dear to me – “what would you like to learn from this text”? The answer was: “how is it even possible that such concerts are being organised in Kyiv right now”? And this question goes beyond just that one evening in the Philharmonic; rather, it concerns the broad subject of how musical institutions manage to function in times of war.

Before leaving for Kyiv, I had several conversations, gathering contacts, and making initial preparations for discussions on-site. I asked a friend (who has been living as a migrant in various EU countries over the past two years) about the Kyiv independent music scene. He told me that the majority of people who made up the indie scene in Kyiv before the fullscale invasion left for the west: to EU countries or to Lviv. He also mentioned the various issues connected to organising events in Kyiv – not only the air-raid alarms, but also curfews and power outages, and perhaps most importantly, the burden of responsibility if a potential tragedy occurs. Not to mention the practice known as “busification”, referring to controls conducted outside various clubs to mobilise so-called “draft dodgers”.

However, the creation of independent culture carries different affects and responsibilities than official cultural institutions – during my stay in Kyiv, I would constantly feel the communal dedication to keep cultural institutions open and functioning, as a kind of testimony to social commitment and an expression of Ukraine’s cultural independence. A few days after the Philharmonic concert, I took part in a meeting, organised as part of the trip, with representatives from various cultural institutions in Kyiv, including Nataliia Stets. This meeting took place in the building of the Khanenko Museum (Національний музей мистецтв імені Богдана та Варвара Ханенків), which can be seen as a symbol of the persistent preservation of activities, and the challenges associated with it, but the experiments as well. This dignified museum, which was established based on a private collection consisting primarily of Early Modern period Western European paintings, had its collections taken down from the walls and secured in the face of the full-scale invasion, and the halls became spaces for temporary exhibitions and the realisation of contemporary operatic experiments conducted by the so-called Opera Aperta laboratory5.

In a space that felt like an incredible, avant-garde, museum-like experiment, Stets spoke about the challenges of running a cultural institution during wartime: for instance, about the special permits required for international performances and the responsibility of identifying “untouchable” musicians from the orchestra who would avoid conscription – and the inability to protect everyone. From the conversations I had in Kyiv, it appears that many institutions of musical life have had to face similar challenges as the Philharmonic – conscription, as well as alarms and power outages, complicate the functioning of ensembles, editorial offices, and schools. At the same time, cultural institutions are undergoing a process of feminisation, the long-term effects of which could be extremely interesting.

What’s more, the cultural and political “mobilisation” of culture opens more opportunities for action. Stets also mentioned the organisation of concerts in public spaces and initiatives aimed at creating new opportunities for young musicians to perform under the auspices of institutions. Cultural policy and diplomacy are supported by the state, which invests in strengthening international connections through various cultural sectors. This applies to both popular music (this summer, Kyiv hosted its first “war” outdoor music festival, and even now I encountered billboards promoting various concerts by Ukrainian bands on the streets) – both for classical music, including contemporary composed music, and jazz-related improvisation.

All of this provides context not only for the concert I attended but also for the entire activity of Ensemble 24 – an institution that is just starting out, but which has emerged from an incredibly interesting environment that is beginning to speak and resonate with its own voice more and more frequently. Even today, this environment – spanning between the aforementioned Octopus Society and the activities of Vere Music Fund and Vere Music Hub – becomes a significant entity in the Ukrainian musical landscape. There are plenty of reasons to believe that the further activities of the ensemble are worth following.

The visit was organised by the Ukrainian Institute in cooperation with The Mieroszewski Centre / Materiał powstał dzięki wizycie studyjnej zorganizowanej przez Centrum Mieroszewskiego i Ukraine Institute.

Iuliia Bentia, Cancelling Russian culture during the war: how it works in Ukrainian music, “Glissando”, https://uc.glissando.pl/en/cancelling/ (accessed here and beyond, November 28, 2024). ↩ ↩

Regarding the conflict surrounding the patron of the Academy, see the same source. It is worth adding that since the publication of Iuliia Bentia’s text, the ties connecting the Academy with its Chinese partners have only strengthened. ↩ ↩

The autumn series of the first three concerts culminated in a November evening at the philharmonic on the 27th, dedicated to corporeality in contemporary music. The program included works by Alexander Schubert, Hyokjae Kim, Franck Bedrossian, Brigitte Muntendorf, Helmut Lachenmann, and Maty Haladzhun, a Ukrainian composer working in Germany (especially in Hamburg), see https://ens24.org/en/2024/07/25/bodyofmusic/. ↩ ↩

Known in Poland from the performance at the Warsaw Autumn 2021, see: https://warszawska-jesien.art.pl/en/2021/programme/programme/21-09/lopuszynska-kurkiewicz-. ↩ ↩

See Julija Bentia, Andrij Kolada, Chornobyldorf – kilka lekcji projektowania przyszłości [Chornobyldorf – a few lessons in designing the future], “Glissando,” https://uc.glissando.pl/pl/chornobyldorf/.” ↩ ↩